Summer has clawed its way up from the Tularosa valley and settled in here at 6000 feet. Tinfiny Ranch is hot. I have few real chores at Tinfiny except the ones I create for myself but keeping my wife cool is one of the prime directives. It’s hot enough to fire up the mini-split air conditioner, electric bill be dammed! I installed the mini-split 4 years ago; in fact I ordered it from China, in China, when me and Berk were out scrambling motorcycles in the Gobi desert. That was after we descended from high atop the Tibetan Plateau…for 40 days.

The mini-split installation was fairly easy: a Magic box that sits outside, a wall-mounted unit inside and a couple of copper pipes with a bit of wiring is all there is to the thing. The unit came pre-charged: all the gas was under pressure inside the magic box. I had to buy a vacuum pump to evacuate the line sets and then open the service valves. Presto! Nice cool air.

Unfortunately, sometime last winter the system sprung a leak: Tinfiny’s mini-split had lost its ability to keep my wife cool. If you’ve read ExhaustNotes.us before you’ll know that I have an aversion to calling in a repairman. Hiring someone who knows what they are doing clashes with the pioneer spirit here at Tinfiny. I googled the F3 error code and found the gas charge was low so I ordered an 11-pound container of 410A refrigerant. Pretty in pink and $80 with free shipping.

The tools required for the air conditioning trade used to be fairly expensive. A set of gauges and a vacuum pump might set you back $500 in the 1980s. A typical homeowner usually didn’t have that kind of equipment sitting next to the rake and that broken blue plastic kiddie pool. Thanks to the wonders of our modern global economy a middleclass pencil-pusher can set himself up in the air conditioning business for a couple hundred very devalued US dollars. Less if he doesn’t care to know what pressures his system runs.

Mini-split air conditioning systems are pretty simple at the mechanical-cooling level. A compressor squeezes the refrigerant gas into a liquid, increasing its heat. This hot, liquid refrigerant is then run through a condenser, which is nothing more than a radiator like the one in your car. The condenser cools the liquid refrigerant by transferring heat from the liquid to the outside air via the cooling fins of the condenser.

Next the cooled liquid refrigerant goes to the expansion valve. The expansion valve has a tiny hole that causes a pressure differential. The now low-pressure refrigerant travels to the evaporator which is another radiator located inside the room to be cooled. The room air temperature boils or expands the refrigerant, in the process drawing heat out of the room. After absorbing heat from the cooled space the refrigerant travels back to the compressor to start the cycle anew.

As this endless circle of suck, squeeze, condense, evaporate, return continues the room gets cooler and cooler until the thermostat shuts off the compressor or the room gets so cold the refrigerant won’t evaporate. Don’t hold your breath for the room to get that cold. While refrigeration theory is simple, all the extra components, controls and electronics involved with air-conditioning are not simple.

An interesting side note about mini-splits: The expansion valve is located inside the compressor/condenser unit that sits outside. This means that both refrigerant tubes going to the interior-mounted evaporator/fan unit are all part of the expansion cycle so both tubes get cold as opposed to one line hot, one line cold like in a traditional central air system.

Have all the fair-weather readers left the room? Good, because we’ve lost anyone with a functioning life and things are about to get even geekier. On my mini-split the only access for a pressure gauge is on the low-pressure side near the intake of the compressor. Gauge sets are usually the first thing a person buys when working on an air conditioner but to me they are the least important tool. My AC guru, Jerry, from The Florida Keys told me to feed the 410A in slowly until the evaporator gets uniformly cool and you’ve reached the right pressure. Who cares what the pressures are as long as the room gets cool, right?

I put the pressure gauge/manifold on the system anyway and fed a steady diet of 410A into the low-pressure side keeping things around 100-psi and it worked. For about 3 hours we had glorious cool air. My wife was happy. Was it me, or did each pass through the compressor seem like a little less cool air was blowing out? I had a leak. I kind of knew I had a leak before I started the filling process because it’s a sealed system: what else could cause low pressure?

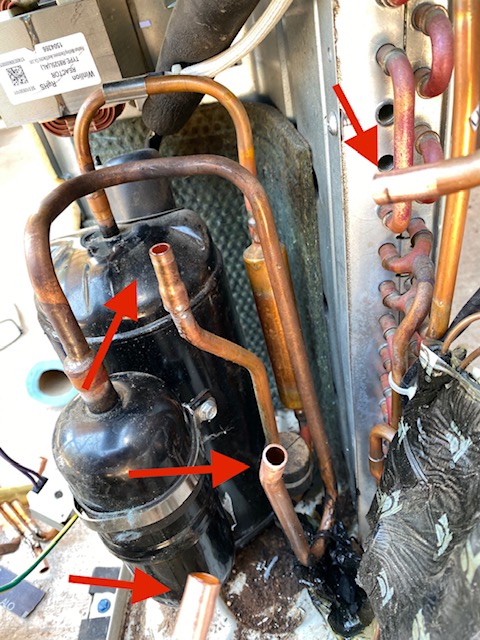

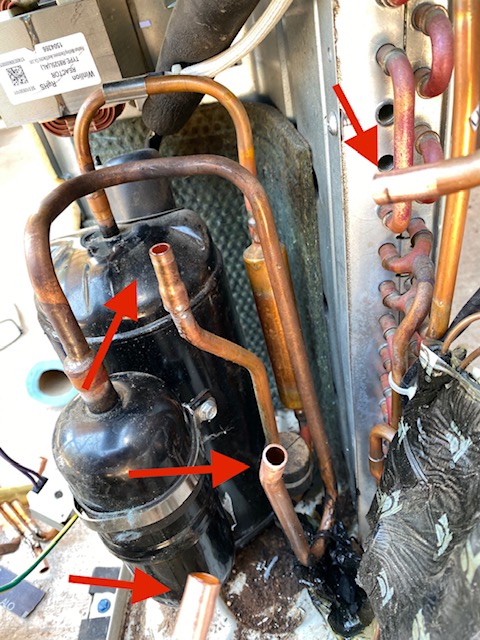

Much like finding a leak on a flat tire, soapy water revealed that the reversing valve was leaking where the tubes were soldered into the spool valve body. A quick note on reversing valves: They do exactly what they say they do. They reverse the direction refrigerant flows in the system making the evaporator the condenser and the condenser the evaporator. In reverse cycle, the unit tries to cool the outdoors and the interior unit warms the house. It makes a fairly efficient heat source as there are no heat strips or high wattage elements to suck up huge quantities of electricity.

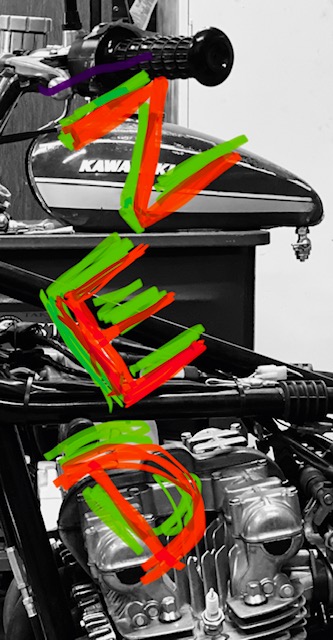

The operative word in mini-split land is “mini.” Everything is crammed together inside a small space making the valve swap more difficult than it needed to be. There are three short pipes almost touching each other and then one more off to the side. To remove the valve gracefully you’d need to heat all 4 joints at once. I don’t have 4 torches or 4 hands so I cut the old valve out. I then tried to de-solder the left over stubs but whatever the manufacturer used to solder their joints had a higher melting point than the copper pipe! The job was turning bad, man. The copper pipe would turn rubbery and that damn solder still would not let go. The wiring and insulation were catching on fire. I had to take a break.

My new plan was to abandon the old joints and cut each tube, lowering the valve a bit but I couldn’t find my small tubing cutter. I had to bend each pipe out of the restricted space to cut them. Of course you know any time you move pipes that have sat in position for years the risk of creating another leak is pretty much 100%. Manhandling the copper pipes back into position was another chore and I began to mentally prepare myself for the cost of a new AC unit ($600).

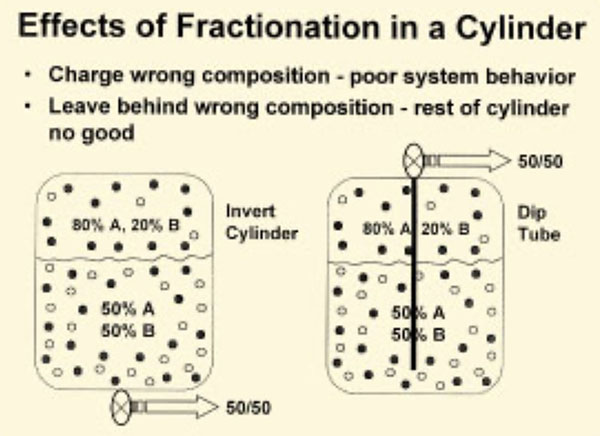

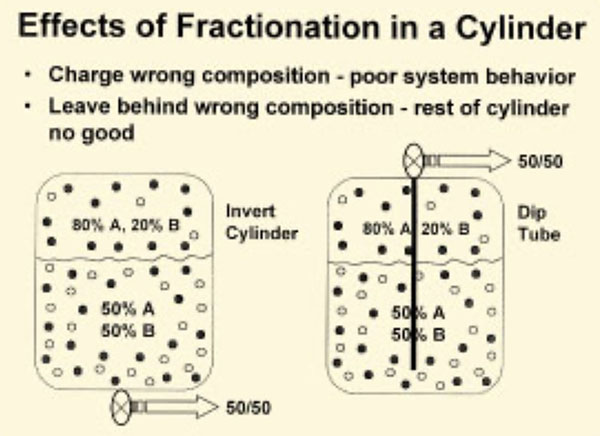

If you’ve lost all the gas out of your mini-split system the best way to charge it is to weigh in the correct amount of refrigerant (32 ounces in this case, plus a few ounces for the tubing runs). I guess now would be a good time to discuss the merits of filling liquid vs gas. Depending on the orientation of the gas bottle you’ll get liquid refrigerant or gas refrigerant out of the bottle. From what I’ve read online liquid charging preserves the ratio of the blended crap they sell us now to close that Ozone hole and save mankind. Sure it worked, the hole closed and all but what about my rights? Gas charging ends up favoring the lighter elements of the blend so each fill alters the ratio of the remaining refrigerant. Worst case it will decrease cooling performance and leave behind a compromised bottle of AC juice. 410A is not as bad as some of the other exotic blends but I liquid charged anyway because I’m a cutting edge, risk taking sort of dude.

In actual fact as soon as the liquid hits a pressure differential it turns to a gas. Things like your pressure gauge manifold knobs turn into expansion valves. As long as you don’t dump the juice in too fast and lock up the compressor with a slug of liquid 410A. Keep the stuff coming out the bottle liquid and your ratios will remain correct.

32 ounces of 410A bought us another few hours of nice, cool air before the mini-split began blowing room temperature air into Tinfiny’s living room (if you can call it living). The thing was still leaking. I never let a crisis go by without using it as an excuse to buy more tools. I used my new halogen sniffer on the condensing unit and found the new expansion valve leaking at my solder joints.

In retrospect I was rushing the job, frustrated with the confined space, fires and tired of messing with the stupid thing. I guess I didn’t get the pipes cleaned off enough or there might have been traces of oil that the solder flux didn’t get clean or who knows. The new valve passed the vacuum test but vacuum is nothing compared to the 300+psi high side running pressure.

Luckily a cool spell blew through Tinfiny Ranch, which bought me some time to think. I asked myself what was the main obstacle to success on this job? The main obstacle was the confined area to work on the valve. Then I said to myself, “Why not get rid of the valve?” it was like the blinding light of Jesus struck me! Of course! Make it cool only and I’ll worry about heat next winter!

And so on the third day of working on the mini-split I bypassed the reversing valve. Using my new mini tubing cutter I made cuts in the pipe at different levels and wide apart, filling the gaps in the plumbing with new copper pipe. This also allowed me to use my new tubing expander on the jumper pipes. Anytime you can eliminate a solder joint it’s a good thing. The tubing expander gets rid of couplings and saves solder joints.

When I bought the pink, 11-pound bottle of 410A I figured it would last the rest of my life. After charging the system twice I was starting to worry I wouldn’t have enough gas to finish the job. I sanded the pipes with crocus cloth and wiped them down with paste flux. I might have gone a bit overboard with the solder as the stuff was running down the pipe. Usually when I solder copper pipe I let the solder wick into the joint then wipe the joints with a rag while the solder is still soft. It makes a clean looking joint. This time I didn’t touch anything for fear of causing a leak.

With the bypass pipes in place I charged the system yet again. 34 ounces of 410A put the low-side pressure near enough to 110 psi so I was in the ballpark charge-wise. Daytime temps have been in the mid-90’s and as I type this the mini-split has been cooling Tinfiny down to a crisp 70 degrees inside. And it’s been doing it for almost 5 days. If there’s a leak it’s a slow one.

Money-wise I may have to call it a wash. I bought a digital scale, a halogen sniffer, a mini tubing cutter, a bottle of 410A, a tubing expander and the rest of the tools I already owned. Maybe calling a pro would have been the way to go. I spent 3 days learning a lot about HVAC, cussing and thinking hard about the choices I make. And I would do the same thing again. It’s a good thing to peek inside the magic boxes of your life.

You know, I did one of the very first San Gabriel videos when those bikes first came to America. It, too, was a hoot.

You know, I did one of the very first San Gabriel videos when those bikes first came to America. It, too, was a hoot.