By Bobbie Surber

Embarking on a spontaneous journey this past October to explore multiple national parks, my dependable Triumph Tiger 900 GT Pro (Tippi), and I escaped from an approaching winter. The objective? An inspiring tour encompassing White Sands, Carlsbad Caverns, Guadalupe, and the Petrified Forest National Parks. With an insatiable love for national parks, these scenic wonders often become a focal point during my motorcycle travels. Spending around 60-70 percent of my time on the road, I am drawn to these incredible natural havens.

Starting from Sedona on a crisp fall afternoon, I cruised through Oak Creek Canyon, reveling in the solitary road and the vibrant autumn leaves adorning the red rock landscape. Petrified Forest National Park is a familiar stop with ancient petrified logs and captivating vistas.

I continued through the desolate upper desert plains, making my way to Springerville, Arizona, before the next leg of my adventure.

The next morning’s journey steered me toward Faywood Hot Springs in New Mexico, but boy, was it a wild ride! Wrestling with savage winds that rivaled a cyclone, I stumbled upon a rider down on the road. As we righted his bike, we ascertained the downed rider was scraped and bruised but fine. My nerves shot, I sought respite from the tempestuous gusts and made a beeline for Alpine, where winds had gone rogue, hitting outrageous gusts of 80 miles per hour. Amid what seemed to be tornado-like chaos, I found solace in the embrace of snug and hospitable Alpine, Arizona.

Rolling into Faywood Hot Springs in New Mexico a day late due to the windstorms, I was greeted by humble cabins and campsites stretching across the desert with views of distant foothills. As Tippi’s tires crunched on the gravel, I found myself in a moment straight out of a motorcycle comedy flick. Decked out head to toe in my riding gear, I sfound myself in a nudist colony! Out of nowhere two mostly naked gents emerged, strutting towards me to help park my bike. Picture this: two bare souls, one bike, and a dangerous scenario brewing. They helped with the genuine enthusiasm of a nudist biker pit crew, and I could not help but nervously accept. However, my mind raced faster than Tippi’s engine, worrying about potential mishaps—my bike toppling over one of them or an accidental heat encounter with certain sensitive areas. The stakes were high, at least for them, and my concern was off the charts!

With Tippi safely parked (and the naked pit crew miraculously unscathed), I swiftly ditched my gear and clothing for the remainder of the day, joining the affable and entertaining guests at the bathing suit optional pools. Trust me, regaling the encounter turned into a comedic highlight of my adventure, spinning a tale of the night’s shenanigans that truly supported my aforementioned moto flick!

Eager to witness the sunrise and embark on my ride, I packed Tippi. I anticipated a solar eclipse, but not before a detour to the City of Rocks State Park (a hidden gem a few miles away). Although time allowed only a brief hike and a few photographs, the park’s charm put it on my must-return list.

Continuing my journey, a stop at Hatch, New Mexico, promised a feast of authentic Mexican cuisine renowned for its chili. It lived up to its reputation as I dove into a plate of green chili smothered enchiladas. But before my feast the anticipation of the eclipse lingered as I parked by the roadside with Tippi and a few fellow travelers, hoping for an unobstructed view. Unfortunately, a thin veil of clouds dampened our expectations, casting a shadow over the anticipated celestial spectacle, although the shifting light added its own atmospheric drama.

The adventure continued as I resumed my ride, following I-25 to I-70 for a two-hour journey leading me to White Sands National Park. Here, nature unveiled a captivating spectacle as I ventured deeper into the park. The landscape transformed into a mesmerizing sand festival, each mile revealing taller and more majestic sand dunes that stretched endlessly to the horizon. The park’s beauty and ethereal ambiance made my farewell bittersweet.

Leaving enchanting White Sands behind, I ventured onward, headed for Cloudcroft, New Mexico, where a charming hostel awaited. This oasis in the mountains promised a restful evening, a sanctuary after a day filled with unexpected turns and nature’s breathtaking displays. I am a huge fan of hostels while traveling solo, not only for the inexpensive lodging but also for the opportunity to meet with fellow adventurers. Cloudcroft Hostel did not disappoint! It is labor of love by a transplant named Stephanie, a fellow rider from Germany. The night’s stay even included a house concert with a traveling performer. I drifted off to sleep that night with the thought of returning to this delightful place.

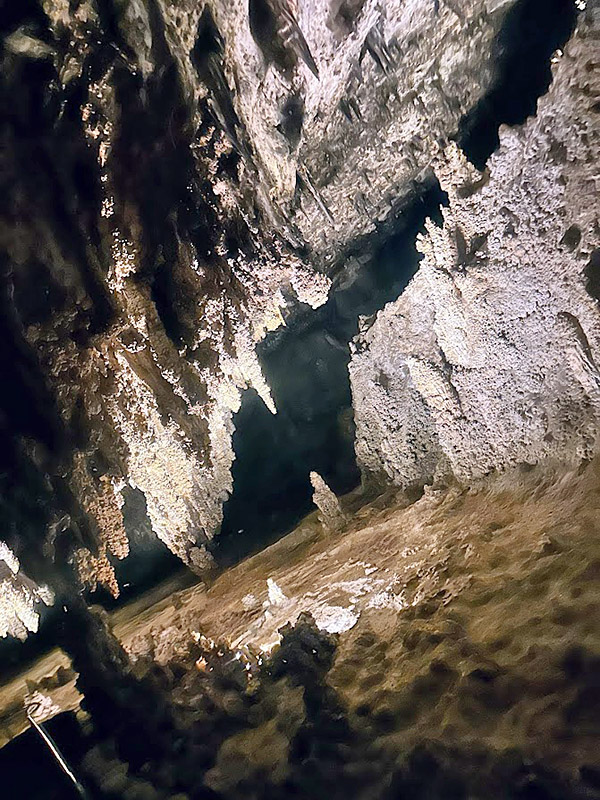

Bright and early the following morning, I embarked on a dual adventure to Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe National Park. My first stop was in Carlsbad, where I had a planned visit with a fellow rider. Parker and I arranged to meet at a historic restaurant. Meeting this captivating rider in person matched the fascination I felt from afar. Our interaction was brief as I had to rush to make my 1:00 p.m. to the caverns. Negotiating the winding roads with enthusiasm, I navigated to the visitor center while maneuvering through the curves, passing slower vehicles, and arriving on time. The caverns exceeded expectations, and I leisurely explored the most picturesque chambers.

Daylight was fleeing, and I knew I had to rush to Guadalupe National Park before sunset. To my delight, a pleasant surprise awaited me as Parker joined me. Guadalupe, an unassuming jewel of a desert park boasting Texas’s highest peak, instantly captured my heart with its desert sunset over the rugged peaks. The night flew by quickly as I prodded Parker for more tales of his exhilarating riding adventures. It made this stop an unforgettable highlight.

The following morning greeted me with thoughts swirling about the completion of my four-park tour and the route home. In a moment of whimsy, I yearned to revisit Cloudcroft for another night. Such impulses are the joys of traveling by bike…logic takes a backseat to wanderlust! Retracing the previous day’s path, I arrived in the afternoon, affording me a chance to explore the historic downtown area.

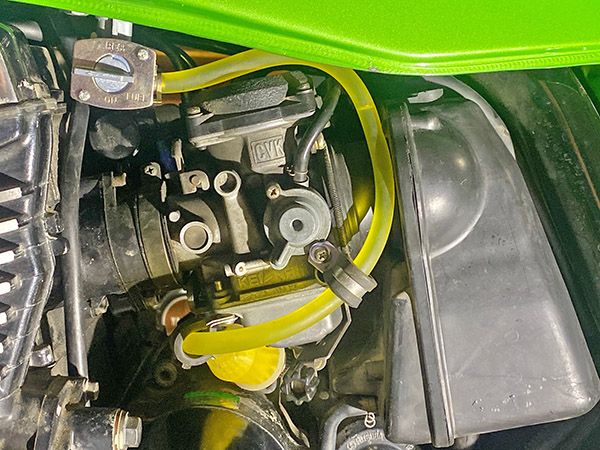

In a move that defied logic (as is the norm in my travels), I reasoned that it made perfect sense to detour back home through Mesa, Arizona, for my bike’s much-needed service. The return ride, riddled with its own set of challenges, became a tale, featuring unexpected twists and yet another memorable encounter at a unique hot spring. It’s a story for another time!

As I reflect on my incredible journey filled with unexpected encounters, stunning landscapes, and fellow riders’ camaraderie, the allure of the open road and unpredictability of travel are the true treasures of my motorcycle expeditions. Each detour, unplanned stop, and quirky encounter combined to create a tapestry of unforgettable experiences. It is what fuels my passion for exploration and two wheel travel. Until the next adventure beckons, I will carry these memories as fuel for the road ahead.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Don’t forget: Visit our advertisers!

OK, well the successful part ended rather quickly. I started off just crushing it and catching fish almost every time I went camping. I was fishing lakes around Arizona and thought that once I was in California it would only improve. It didn’t. In fact, I didn’t catch a single fish from July to the end of August. In my own defense, I was fishing rivers where most were fly fishing and not using lures or worms. But still, to be skunked day after day for a few months was demoralizing, especially one day when fishing in Lassen National Park. There was a couple next to me, literally right next to me, using the exact same power bait and reeling in bass after bass. As soon as he landed a fish his wife would clean and cook them on the spot. Meanwhile, I wasn’t even getting a bite. I may have cried that night in my tent a little (or a lot). I kept a positive outlook, as I was just starting my trip and had so many states to visit that my luck would surely turn around.

OK, well the successful part ended rather quickly. I started off just crushing it and catching fish almost every time I went camping. I was fishing lakes around Arizona and thought that once I was in California it would only improve. It didn’t. In fact, I didn’t catch a single fish from July to the end of August. In my own defense, I was fishing rivers where most were fly fishing and not using lures or worms. But still, to be skunked day after day for a few months was demoralizing, especially one day when fishing in Lassen National Park. There was a couple next to me, literally right next to me, using the exact same power bait and reeling in bass after bass. As soon as he landed a fish his wife would clean and cook them on the spot. Meanwhile, I wasn’t even getting a bite. I may have cried that night in my tent a little (or a lot). I kept a positive outlook, as I was just starting my trip and had so many states to visit that my luck would surely turn around.

It was definitely time to return to the United States. It didn’t take too long over the next week to pack up, deflate the leaky air mattress I had been sleeping on for 8 months, and place the Good Will furniture on the corner (the furniture and I shared the same situation; we were both looking for our next home). Loading everything into the car was the final step before getting on the Tsawwassen Ferry, which would bring me to Vancouver. It was a short and uneventful 3-hour drive to my new residence in Seattle, Washington.

It was definitely time to return to the United States. It didn’t take too long over the next week to pack up, deflate the leaky air mattress I had been sleeping on for 8 months, and place the Good Will furniture on the corner (the furniture and I shared the same situation; we were both looking for our next home). Loading everything into the car was the final step before getting on the Tsawwassen Ferry, which would bring me to Vancouver. It was a short and uneventful 3-hour drive to my new residence in Seattle, Washington.