I saw the advertisement for The Bomber in our local Holloman Bookoo website. Holloman Bookoo is like Craigslist but more local. There may be other BooKoo sites but I haven’t searched for them because the stuff for sale is too far away. This story gets a bit complicated but I was searching for a drive train to scavenge for Brumby, my Jeep YJ.

The Bomber, a half-ton 1990 4X4 GMC Suburban, had 3:73 axles, a running throttle-body fuel-injected small-block engine and was the last year of the solid front axle Suburbans. 1989 and 1990 were odd years for Suburbans because the rest of GM’s truck line changed body styles in 1988. For some reason the Suburban didn’t make the cut and soldiered on with the classic Square Body until joining the rest of the gang in 1991. Except for logos, the Chevy and GMC versions are pretty much exactly alike.

The Bomber’s half-ton, six-lug front axle is GM’s take on a Dana 44. I watched a Dirt Every Day video that said 1989/1990 models received axle shaft upgrades and were maybe a bit better than the D44. All this was good news for Brumby because the transmission had lost a gear and the little YJ desperately needed more power.

The Bomber’s owner wanted $1800. I drove the big beast around and offered him $1500. It was too easy; did I leave money on the table? CT (my wife) was a little unsure about my plan to strip out the Bomber for a pie-in-the-sky plan to boost the Jeep’s power. The worst time to plan an engine-axle swap is when you have no place to work and are trying to find a house to live in so I put the ménage on the back burner and busied myself with the mundane tasks of life.

The old GMC ran well and I started using it to haul materials. The thing had crazy stiff springs on the rear axle: I could load 2 tons without the axle bottoming out. The 350 small-block, while no powerhouse, could pull the grade to my house without exploding into bits. The door sticker says “Built Flint Tough” and they mean it. The added advantage of a low-range transfer case and four-wheel drive meant I could haul a 10,00 pound, concrete mixer with a yard and a half of mud up Tinfiny’s steep, slippery driveway.

The Bomber came with a custom paint job that could not have been more out of place. It was shocking. CT recommended I cover over the Starsky & Hutch themed wagon if I ever wanted her to ride in the thing. It took less than a quart of BBQ black to roll over the offending stripes. Not that it looks good now, but at least people run away slower.

Shod with smallish but almost new 31” tires, the bomber looked a little cheesy in the tire division. Bigger, 33” tires that would fill the wheel wells were ordered from Wal-Mart. Just like that the Bomber’s value doubled. I put the 31” tires on Brumby the Jeep. Remember the Jeep? The reason I bought the Bomber?

The thing is, a Suburban is handy as hell to have around. I can load it up with bags of concrete or building materials and everything stays dry. We went camping in the beast; there’s over 8 feet of room for bedding if you fold the seats down. The body is dented but rust free. I use the ‘Burb for garbage dump runs and to scare people.

I’ve grown attached to the Bomber. You’ll hear no more talk of swapping drive trains. In fact a whole new list of projects has been created. I need to remove all the interior plastic and rugs from the passenger doors rearward because it’s too hard to keep clean. I want the cargo area bare metal so I can hose it out. The stupid wooden overhead console has to go because I keep hitting my head on the edge. Then the automatic transmission needs to be swapped out for a 4-speed manual. I can’t stand automatics. It’ll need a decent paint job at some point and a roof rack with one of those tents on top.

Worst of all I’m still on the lookout for a V-8 drive train to swap into the Jeep.

Never miss an ExNotes blog…sign up here for free!

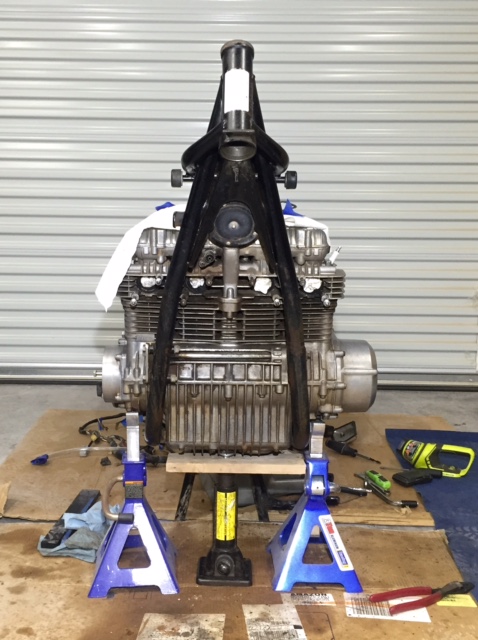

After trimming some rubber flashing where the brass manifold vacuum ports enter the new rubber manifolds I managed to get them installed without stripping any more 6mm screws. The manifold clamps are soaking in Evapo-rust as we type.

After trimming some rubber flashing where the brass manifold vacuum ports enter the new rubber manifolds I managed to get them installed without stripping any more 6mm screws. The manifold clamps are soaking in Evapo-rust as we type. Next I checked the valve adjustment because I’ll be starting the beast soon and I don’t want to fight the system if the valves are way out of adjustment. Before removing the valve cover I marked the front in case it matters.

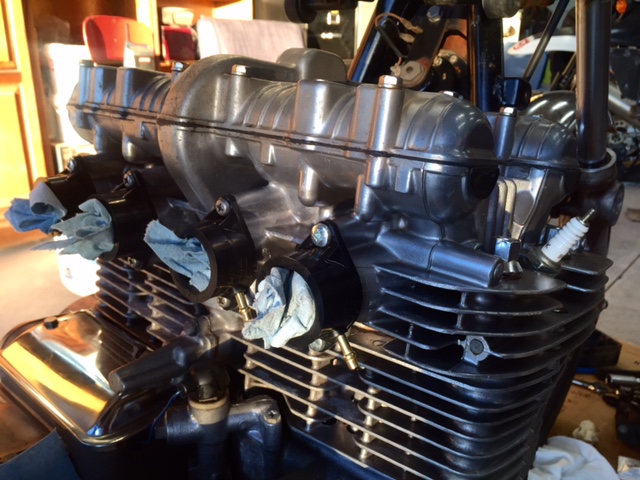

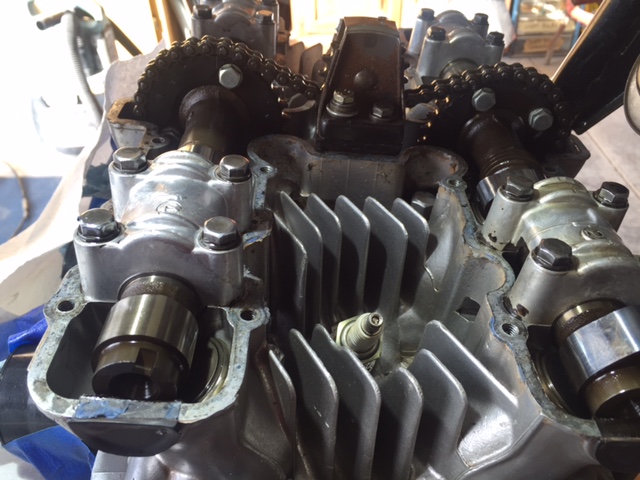

Next I checked the valve adjustment because I’ll be starting the beast soon and I don’t want to fight the system if the valves are way out of adjustment. Before removing the valve cover I marked the front in case it matters. The cams and valve shims look unworn. This bike shows 41,000 miles on the odometer! If this were a Honda the cam lobes would be galled. I know this because almost every Honda I’ve owned galled its cam lobes.

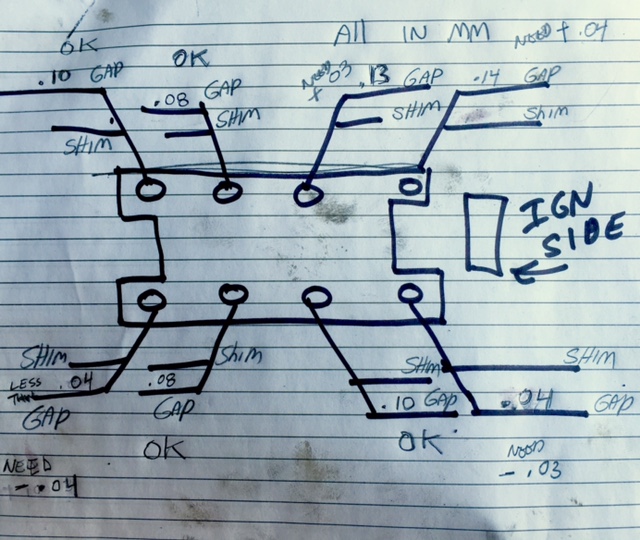

The cams and valve shims look unworn. This bike shows 41,000 miles on the odometer! If this were a Honda the cam lobes would be galled. I know this because almost every Honda I’ve owned galled its cam lobes. The valves are close enough to start the engine, two are on the tight side and two are on the loose side. Four valves are within spec. I’ll recheck everything after starting the engine in case a chunk of carbon or a mouse paw is affecting these readings.

The valves are close enough to start the engine, two are on the tight side and two are on the loose side. Four valves are within spec. I’ll recheck everything after starting the engine in case a chunk of carbon or a mouse paw is affecting these readings. Zed’s clutch cable is in bad shape so I removed the clutch actuator housing/sprocket cover for replacement and cleaning/lube/adjustment. Inside I found the neutral light indicator switch broken off. I don’t think a ton of oil would have spewed out as the hole is not pressurized but it most likely would have leaked.

Zed’s clutch cable is in bad shape so I removed the clutch actuator housing/sprocket cover for replacement and cleaning/lube/adjustment. Inside I found the neutral light indicator switch broken off. I don’t think a ton of oil would have spewed out as the hole is not pressurized but it most likely would have leaked. Zed appears to be going backwards but trust me she’s making progress. With the front of the bike jacked up you couldn’t miss the loose steering head bearings. Rather than just tighten them I took the forks apart to re-grease them. Much like removing the sprocket cover it’s a good thing I did. The top bearing looks fine but the bottom is pretty rusty. I’ve cleaned this mess up and in a pinch the bottom bearing, while pitted, could be used again but I’ll order new bearings. I’m in no mood to take the front apart again.

Zed appears to be going backwards but trust me she’s making progress. With the front of the bike jacked up you couldn’t miss the loose steering head bearings. Rather than just tighten them I took the forks apart to re-grease them. Much like removing the sprocket cover it’s a good thing I did. The top bearing looks fine but the bottom is pretty rusty. I’ve cleaned this mess up and in a pinch the bottom bearing, while pitted, could be used again but I’ll order new bearings. I’m in no mood to take the front apart again. Zed’s fork seals were leaking. Another stroke of luck as the oil kept the lower section of the fork tubes from rusting. Under the headlamp ears the rust is worse. I’ll clean it off and coat that section with grease when I reassemble the forks. You’ll never see it. I’ve started cleaning the fork legs in preparation for disassembly. You probably already know this but remember to loosen the big bolt on top of the fork tube before removing the tubes and loosen the allen-head bolt on the bottom of the fork sliders (under the axle boss) before removing that big top bolt.

Zed’s fork seals were leaking. Another stroke of luck as the oil kept the lower section of the fork tubes from rusting. Under the headlamp ears the rust is worse. I’ll clean it off and coat that section with grease when I reassemble the forks. You’ll never see it. I’ve started cleaning the fork legs in preparation for disassembly. You probably already know this but remember to loosen the big bolt on top of the fork tube before removing the tubes and loosen the allen-head bolt on the bottom of the fork sliders (under the axle boss) before removing that big top bolt. My buddy Skip sent what we hope is the correct spark advancer unit so Zed should have everything it needs to start soon. I’m a little concerned that I can only find first gear and neutral in the transmission. Hopefully, once the engine starts and oil is slung around the gearbox will shift.

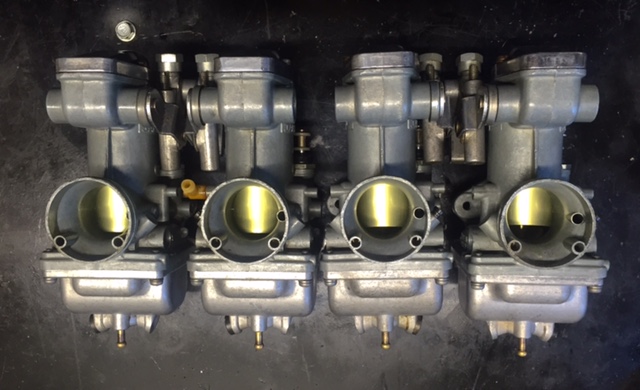

My buddy Skip sent what we hope is the correct spark advancer unit so Zed should have everything it needs to start soon. I’m a little concerned that I can only find first gear and neutral in the transmission. Hopefully, once the engine starts and oil is slung around the gearbox will shift. I’ve been spending some time with Zed’s carburetors, working on details that required home-brewed engineering. The Mikuni carbs on Zed don’t have a traditional choke (a flap that blocks air going into the carb causing a rich mixture) but we still call it a choke. Instead, Zed’s carbs employ an enrichener circuit, which is more like a tiny, completely separate carburetor grafted onto the main body of the carb. Sort of like the brain inside Krang’s stomach on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon. The enrichener has its own air intake on the upwind side of the throttle slide. This fuel circuit is fixed; no adjustment needed and is controlled by a plunger on the downwind side of the throttle slide. Lifting the plunger allows air to flow through the tiny carburetor at a pre-set fuel/air mixture and if everything else is right, helps a cold Kawasaki engine start better.

I’ve been spending some time with Zed’s carburetors, working on details that required home-brewed engineering. The Mikuni carbs on Zed don’t have a traditional choke (a flap that blocks air going into the carb causing a rich mixture) but we still call it a choke. Instead, Zed’s carbs employ an enrichener circuit, which is more like a tiny, completely separate carburetor grafted onto the main body of the carb. Sort of like the brain inside Krang’s stomach on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon. The enrichener has its own air intake on the upwind side of the throttle slide. This fuel circuit is fixed; no adjustment needed and is controlled by a plunger on the downwind side of the throttle slide. Lifting the plunger allows air to flow through the tiny carburetor at a pre-set fuel/air mixture and if everything else is right, helps a cold Kawasaki engine start better. Back to square one. I noticed how the bobbin was nearly the same size as the pop rivets I’d been using to assemble parts of Tinfiny’s generator room. I have about 500 of these rivets in stock so I could afford to lose a few. Knocking the pin out of the pop rivet revealed a bore just a wee bit small for the plunger shaft but it was not a problem to run a drill bit through making the bore an exact fit for the plunger. A pop rivet only has one flanged side so I repeated the process on a second rivet, cut the two rivets to equal the length of a factory bobbin and assembled the mess. I cannot wait for a hard-core Z1 enthusiast to happen upon the aluminum bobbin. It’ll probably cause a heart attack as most Z1 fans are around 75 years old.

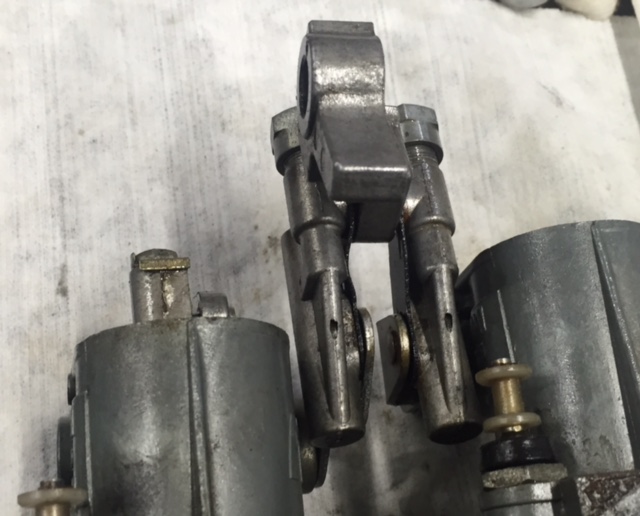

Back to square one. I noticed how the bobbin was nearly the same size as the pop rivets I’d been using to assemble parts of Tinfiny’s generator room. I have about 500 of these rivets in stock so I could afford to lose a few. Knocking the pin out of the pop rivet revealed a bore just a wee bit small for the plunger shaft but it was not a problem to run a drill bit through making the bore an exact fit for the plunger. A pop rivet only has one flanged side so I repeated the process on a second rivet, cut the two rivets to equal the length of a factory bobbin and assembled the mess. I cannot wait for a hard-core Z1 enthusiast to happen upon the aluminum bobbin. It’ll probably cause a heart attack as most Z1 fans are around 75 years old. Between the throttle linkage pivots on each set of two carbs there are little dust covers made from a treated black paper. Or maybe the dust covers are rubber, I can’t tell. Three of the four covers were broken on Zed. The covers go over the springs and ball joints on the linkage. They don’t seal all that well but might keep a larger bug from crawling in there.

Between the throttle linkage pivots on each set of two carbs there are little dust covers made from a treated black paper. Or maybe the dust covers are rubber, I can’t tell. Three of the four covers were broken on Zed. The covers go over the springs and ball joints on the linkage. They don’t seal all that well but might keep a larger bug from crawling in there. This is a part I didn’t bother looking for because I can make new ones in less time than it takes to look them up and order them. I used the thin plastic lid from a box of self-tapping sheet metal screws. Without a lid you know the screws are going to end up scattered across the shed floor. The dust covers didn’t come out as nice as I would have liked. Luckily, once installed you can’t see the things.

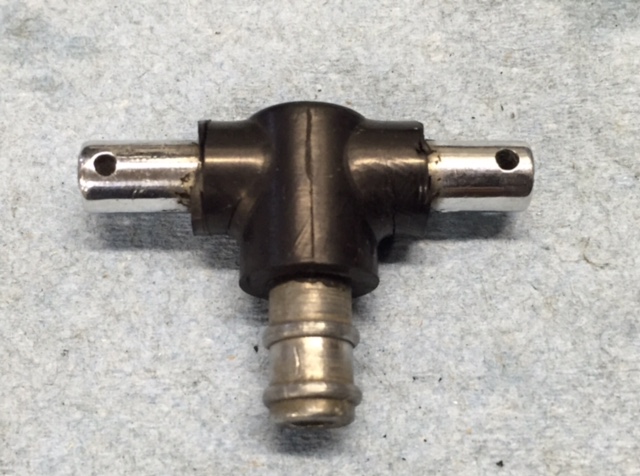

This is a part I didn’t bother looking for because I can make new ones in less time than it takes to look them up and order them. I used the thin plastic lid from a box of self-tapping sheet metal screws. Without a lid you know the screws are going to end up scattered across the shed floor. The dust covers didn’t come out as nice as I would have liked. Luckily, once installed you can’t see the things. On the Z1 900cc, each set of two carbs share a fuel inlet pipe. The pipe goes between the carbs and is a metal Tee fitting with thick rubber o-rings cast onto the straight section of the Tee. This rubber hardens and shrinks resulting in a loose, leaky fit. You can buy new ones for 34 dollars but if you’ve read Zed’s Not Dead this far you know what is going to happen next.

On the Z1 900cc, each set of two carbs share a fuel inlet pipe. The pipe goes between the carbs and is a metal Tee fitting with thick rubber o-rings cast onto the straight section of the Tee. This rubber hardens and shrinks resulting in a loose, leaky fit. You can buy new ones for 34 dollars but if you’ve read Zed’s Not Dead this far you know what is going to happen next. I cut the rubber away from the fuel pipe and polished the exposed metal to ensure a smooth sealing surface. Then I drilled a small hole near the end of the pipe in order to install a pin (made from the drill bit). The pin is the same length as the width of the fuel inlet bore so once it is installed in the carb body the pin can’t fall out.

I cut the rubber away from the fuel pipe and polished the exposed metal to ensure a smooth sealing surface. Then I drilled a small hole near the end of the pipe in order to install a pin (made from the drill bit). The pin is the same length as the width of the fuel inlet bore so once it is installed in the carb body the pin can’t fall out. Now I used a ¼-inch length of rubber fuel hose (be sure to use the non-reinforced hose as cloth reinforcing strands will wick fuel, causing a leak) and slid this hose onto the fuel Tee. Next came washers and finally the pin. The assembly fits snugly into the carburetors. It helps to put the fuel feed hose on before you slide the carbs together. Hopefully it won’t leak.

Now I used a ¼-inch length of rubber fuel hose (be sure to use the non-reinforced hose as cloth reinforcing strands will wick fuel, causing a leak) and slid this hose onto the fuel Tee. Next came washers and finally the pin. The assembly fits snugly into the carburetors. It helps to put the fuel feed hose on before you slide the carbs together. Hopefully it won’t leak. I’ve got the carbs assembled onto the rack and everything seems to work smoothly. I’ll be testing the float levels on the bench and will sync the throttle slides as close as I can get them. The idea being all four slides move the same distance in unison. Even if they’re not perfect the bike should run reasonably well. Later, manifold vacuum gauges can be used to adjust the carbs for any slight differences between cylinders.

I’ve got the carbs assembled onto the rack and everything seems to work smoothly. I’ll be testing the float levels on the bench and will sync the throttle slides as close as I can get them. The idea being all four slides move the same distance in unison. Even if they’re not perfect the bike should run reasonably well. Later, manifold vacuum gauges can be used to adjust the carbs for any slight differences between cylinders. One of my moto buddies stopped by Tinfiny Ranch, our high desert lair in New Mexico, and in the course of showing him around the property we got to talking about how incomplete everything was. He called it the 70% rule. As in 70% is close enough and time to move on to another project.

One of my moto buddies stopped by Tinfiny Ranch, our high desert lair in New Mexico, and in the course of showing him around the property we got to talking about how incomplete everything was. He called it the 70% rule. As in 70% is close enough and time to move on to another project. I’d like to have a concrete floor in Tinfiny’s shed. I’ve been working on it. Sadly, only around 25% of the floor is concrete leaving 75% (AKA the lion’s share) dirt. It’s a solid sort of dirt though, and not much water runs under the building’s edge when it rains, unless it rains really hard. Then it gets a bit muddy. It would have been a heck of a lot easier to pour the slab first, then put the building up but that ship has sailed.

I’d like to have a concrete floor in Tinfiny’s shed. I’ve been working on it. Sadly, only around 25% of the floor is concrete leaving 75% (AKA the lion’s share) dirt. It’s a solid sort of dirt though, and not much water runs under the building’s edge when it rains, unless it rains really hard. Then it gets a bit muddy. It would have been a heck of a lot easier to pour the slab first, then put the building up but that ship has sailed. I’ve nearly finished the water system. There’s a 2500-gallon tank being fed rainwater from half of the shed roof. I plan to gutter the other half some day but first I have to finish those 24-volt circuits to get the pressure pump working. I know the pump works ok because I’ve rigged it up to an 18-volt Ryobi battery. It’s just temporary, you know? There’s a pesky leak on one of the Big Blue filters. I’ve taken the canister apart several times but it still leaks from the large o-ring recessed into the canister. I leave the Ryobi battery out of the jury-rigged power connector when I don’t need water. That slows the leak quite a bit.

I’ve nearly finished the water system. There’s a 2500-gallon tank being fed rainwater from half of the shed roof. I plan to gutter the other half some day but first I have to finish those 24-volt circuits to get the pressure pump working. I know the pump works ok because I’ve rigged it up to an 18-volt Ryobi battery. It’s just temporary, you know? There’s a pesky leak on one of the Big Blue filters. I’ve taken the canister apart several times but it still leaks from the large o-ring recessed into the canister. I leave the Ryobi battery out of the jury-rigged power connector when I don’t need water. That slows the leak quite a bit. When you are off-grid you need a generator as backup in case a series of cloudy days runs the battery-bank down. Of course, the generator needs its own well-ventilated, soundproofed shed to keep the generator out of the elements and not drive everyone within a 4 square mile area crazy. I have almost finished the generator shed. I’ve got the floor poured, the wiring to the solar-generator transfer switch installed and complete but for some reason the wheels came off and the project stalled.

When you are off-grid you need a generator as backup in case a series of cloudy days runs the battery-bank down. Of course, the generator needs its own well-ventilated, soundproofed shed to keep the generator out of the elements and not drive everyone within a 4 square mile area crazy. I have almost finished the generator shed. I’ve got the floor poured, the wiring to the solar-generator transfer switch installed and complete but for some reason the wheels came off and the project stalled. Lately I’ve been tinkering with an

Lately I’ve been tinkering with an

The reason lefty bits are the nads for removing stuck or broken bolts is because of their natural tendency to unscrew whatever they are drilling into. By increasing the bit size in stages hopefully you can get the offending screw so thin that the remaining threads weaken, collapse slightly and wind out of the hole looking like a coil spring. And that’s mostly what happened except the thread came out in pieces.

The reason lefty bits are the nads for removing stuck or broken bolts is because of their natural tendency to unscrew whatever they are drilling into. By increasing the bit size in stages hopefully you can get the offending screw so thin that the remaining threads weaken, collapse slightly and wind out of the hole looking like a coil spring. And that’s mostly what happened except the thread came out in pieces. After clearing out the swarf I ran a bottoming tap into the hole and tidied up the threads as much as possible. I will use a slightly longer screw to compensate for the compromised hole but I’m pretty sure it will be fine and I have avoided using a Helicoil thread repair, which is the hack mechanic’s favorite crutch.

After clearing out the swarf I ran a bottoming tap into the hole and tidied up the threads as much as possible. I will use a slightly longer screw to compensate for the compromised hole but I’m pretty sure it will be fine and I have avoided using a Helicoil thread repair, which is the hack mechanic’s favorite crutch.

I haven’t forgotten about the carburetors either. I’ve been soaking them in Evapor-rust and the stuff is doing a fine job. It’s very mild so you can leave zinc carb bodies immersed for days without fear of eating away the good parts. All four of the carbs are clean and I’m waiting on a few parts before I can reassemble the rack.

I haven’t forgotten about the carburetors either. I’ve been soaking them in Evapor-rust and the stuff is doing a fine job. It’s very mild so you can leave zinc carb bodies immersed for days without fear of eating away the good parts. All four of the carbs are clean and I’m waiting on a few parts before I can reassemble the rack. Zed’s little clutch-cover, oil level window was black with sitting-bike mung. It was so black the oil level could not be determined. I removed the cover and cleaned out behind the metal back-plate. Since I had the cover off I figured it would be a good idea to check the clutch plates for wear. The fibers are within tolerance and the steels are only slightly rusty so I’ll clean all those parts up and Zed should have a functioning clutch.

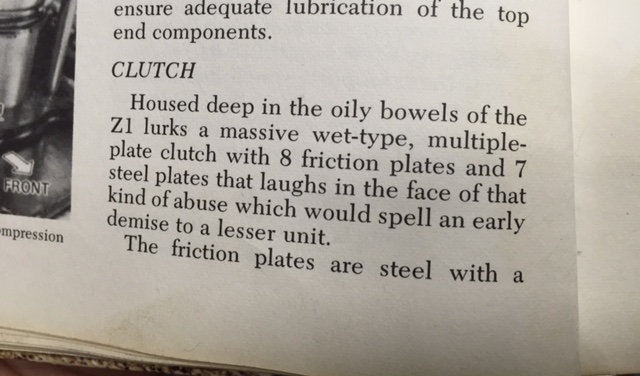

Zed’s little clutch-cover, oil level window was black with sitting-bike mung. It was so black the oil level could not be determined. I removed the cover and cleaned out behind the metal back-plate. Since I had the cover off I figured it would be a good idea to check the clutch plates for wear. The fibers are within tolerance and the steels are only slightly rusty so I’ll clean all those parts up and Zed should have a functioning clutch. When Kawasaki designed the Z1 they went all out. This was Big K’s flagship motorcycle and the robust clutch is a fine example of strength. The large, straight-cut clutch gear would not look out of place in a one-ton manual truck transmission. The fingers that locate the fiber plates are surrounded by a steel band to prevent them from spreading under load. This clutch is awe-inspiring and looks like it could handle double the Z1’s 82 (claimed) horsepower. The bike has 41,000 miles showing on the clock and the metal parts show minimal wear. I am impressed.

When Kawasaki designed the Z1 they went all out. This was Big K’s flagship motorcycle and the robust clutch is a fine example of strength. The large, straight-cut clutch gear would not look out of place in a one-ton manual truck transmission. The fingers that locate the fiber plates are surrounded by a steel band to prevent them from spreading under load. This clutch is awe-inspiring and looks like it could handle double the Z1’s 82 (claimed) horsepower. The bike has 41,000 miles showing on the clock and the metal parts show minimal wear. I am impressed. Don’t take my word for it, here is the author of the Z1 repair manual waxing eloquent over the Z’s clutch.

Don’t take my word for it, here is the author of the Z1 repair manual waxing eloquent over the Z’s clutch. I’m making another list of parts and will be blowing more money on Zed. I really hope this engine runs without a lot of knocking and the transmission shifts like butter.

I’m making another list of parts and will be blowing more money on Zed. I really hope this engine runs without a lot of knocking and the transmission shifts like butter.

Jack Lewis and I used to work for the same motorcycle magazine. We both started at the magazine about the same time. Our moto-journo fortunes seemed linked for 10 years and we both faded from the magazine’s pages nearly in lock step. One month on, one month off: Being platooned with Jack Lewis was like batting cleanup behind Babe Ruth. The crowd would be atwitter over the mammoth home run Jack smashed out into the parking lot, where the cigarette smoking kids would fight each other for the ball. Then it was my turn. No pressure.

Jack Lewis and I used to work for the same motorcycle magazine. We both started at the magazine about the same time. Our moto-journo fortunes seemed linked for 10 years and we both faded from the magazine’s pages nearly in lock step. One month on, one month off: Being platooned with Jack Lewis was like batting cleanup behind Babe Ruth. The crowd would be atwitter over the mammoth home run Jack smashed out into the parking lot, where the cigarette smoking kids would fight each other for the ball. Then it was my turn. No pressure. I drilled the screw in stages until I could try my handy-dandy left-hand drill/remover tool.

I drilled the screw in stages until I could try my handy-dandy left-hand drill/remover tool.

The broken screw is small, like a 4mm, maybe a 6mm and there’s not a lot of room for error. The little extractor tool had a good bite into the screw but the thing would not budge. One thing you don’t want to do is break off an easy out because they are super hard material. There’s no drilling the things and you are well and truly screwed if you manage to get the hole full of busted tool steel. I eased off. Sometimes you make more progress doing nothing rather than doing the wrong thing.

The broken screw is small, like a 4mm, maybe a 6mm and there’s not a lot of room for error. The little extractor tool had a good bite into the screw but the thing would not budge. One thing you don’t want to do is break off an easy out because they are super hard material. There’s no drilling the things and you are well and truly screwed if you manage to get the hole full of busted tool steel. I eased off. Sometimes you make more progress doing nothing rather than doing the wrong thing. Admitting defeat today I decided to step away from the cylinder head and give the hole a few more days soaking with penetrating oil now that I can get to the backside of the situation. In addition to soaking I’ll heat-cycle the aluminum with a 1500-watt heat gun in the hopes of disrupting the steel screw/aluminum head interface. I guess the worse case would be to drill the thing all the way out and use a thread repair insert but I really don’t want to do that. That would be true hackery.

Admitting defeat today I decided to step away from the cylinder head and give the hole a few more days soaking with penetrating oil now that I can get to the backside of the situation. In addition to soaking I’ll heat-cycle the aluminum with a 1500-watt heat gun in the hopes of disrupting the steel screw/aluminum head interface. I guess the worse case would be to drill the thing all the way out and use a thread repair insert but I really don’t want to do that. That would be true hackery. A complete

A complete  Included in the order was an O-ring for the re-sized drain plug and the washer that goes between the oil filter and the oil filter spring. With these parts I managed to get the bottom of the engine buttoned up. Progress has been fitful but Zed is getting closer. I’m really jonesing for concrete so I may have to pull off Zed and pour a yard to keep my soul on ice.

Included in the order was an O-ring for the re-sized drain plug and the washer that goes between the oil filter and the oil filter spring. With these parts I managed to get the bottom of the engine buttoned up. Progress has been fitful but Zed is getting closer. I’m really jonesing for concrete so I may have to pull off Zed and pour a yard to keep my soul on ice. After I made a particularly snarky Facebook comment regarding some newfangled electronic rider aid, a former editor sent me an email asking why I always slag off electronic controls. He asked if I had ever ridden a motorcycle equipped with traction control, wheelie control, engine power selector toggle or one built after 1971.

After I made a particularly snarky Facebook comment regarding some newfangled electronic rider aid, a former editor sent me an email asking why I always slag off electronic controls. He asked if I had ever ridden a motorcycle equipped with traction control, wheelie control, engine power selector toggle or one built after 1971.