By Joe Berk

About three years ago I had dinner with good buddy Robby at a Mexican restaurant outside of Atlanta. Robby bought some sample bullets for me and one of the flavors was a 65-grain 9mm ARX bullet. It was something I had not seen or heard of before.

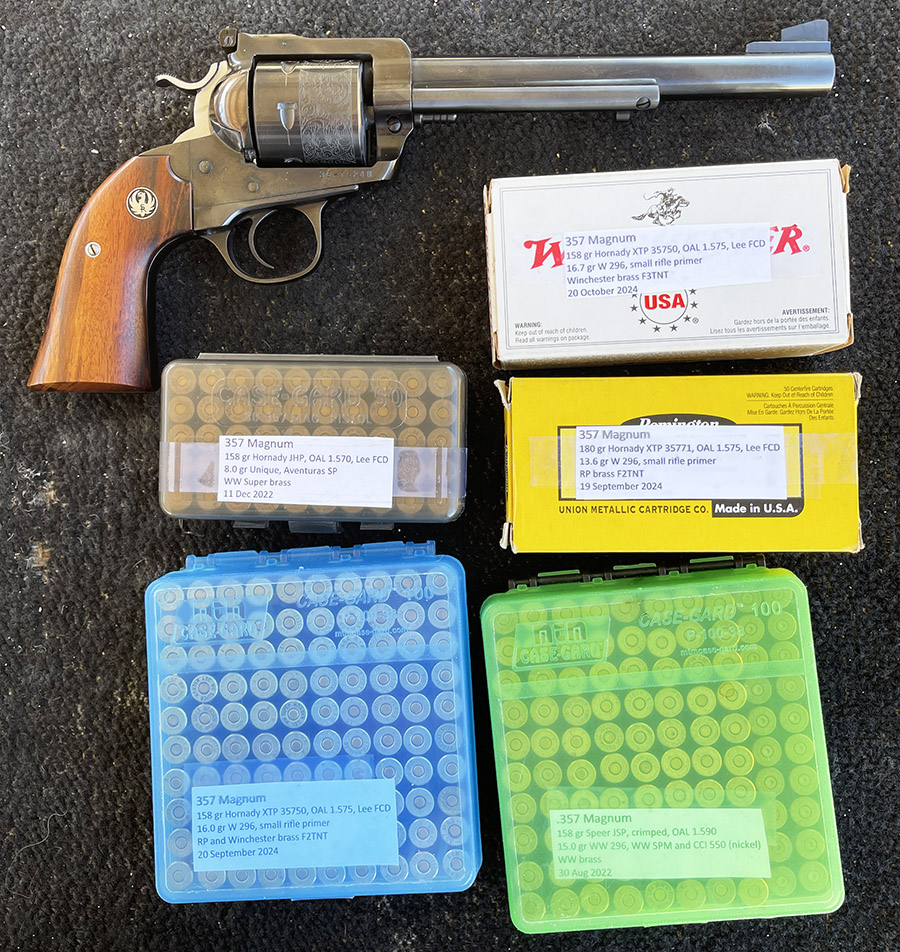

These are frangible lightweight bullets designed to inflict a lot of damage without penetrating walls. The bullets are called a fluted design, and they are a composite copper/polymer material. They are a very high velocity bullet. There are a number of reloading admonitions with these, including not to overcrimp because doing so will break up the bullet. I’m talking like I’m an expert on these; I am not. This is the first time I’ve played with them.

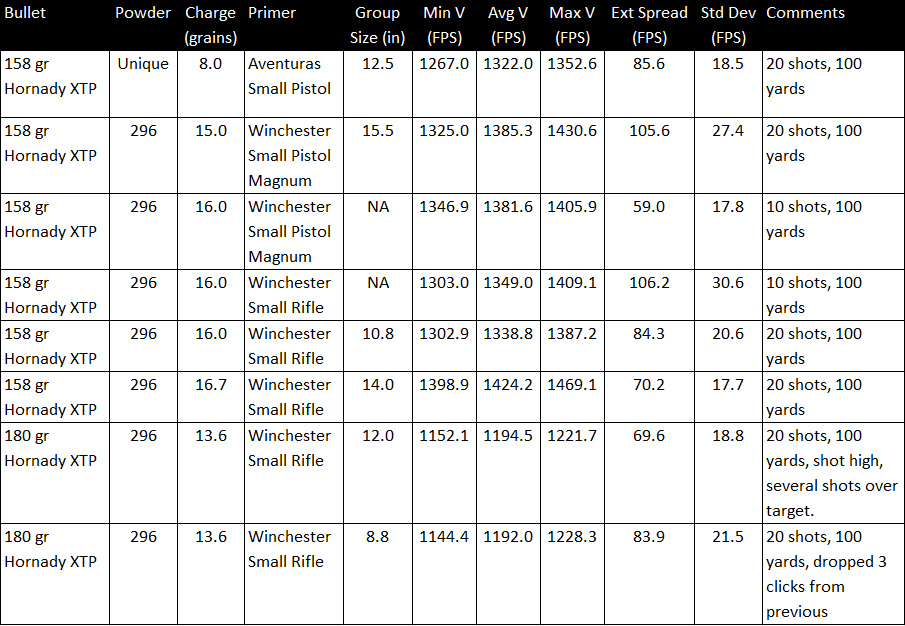

I loaded these with 5.2 grains of Winchester 231. That powder is the same as HP 38, and I found a load for HP 38. I’m thought I would get something like 1400 fps with this load based on what I saw on the Hodgdon site. Other powders provide more velocity, but I loaded with what I had on hand (and that was Winchester 231).

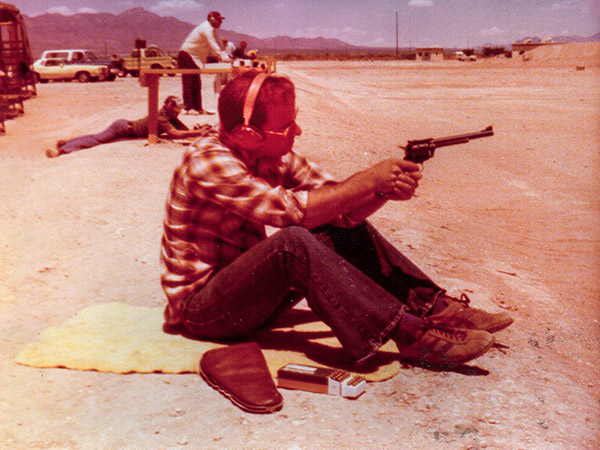

I loaded on Thursday and fired these the next day, testing for velocity, reliability, and accuracy in two 9mm handguns. Those were a 1911 (with a 5-inch barrel) and a Smith and Wesson Shield (with a 3.1-inch barrel). From what I had read in online reviews, the ARX bullets are supposed to be relatively accurate. I expected them to shoot way low (as lighter bullets in handguns generally do). The loaded ammo looks cool, and the ARX bullets are relatively inexpensive at $39/500.

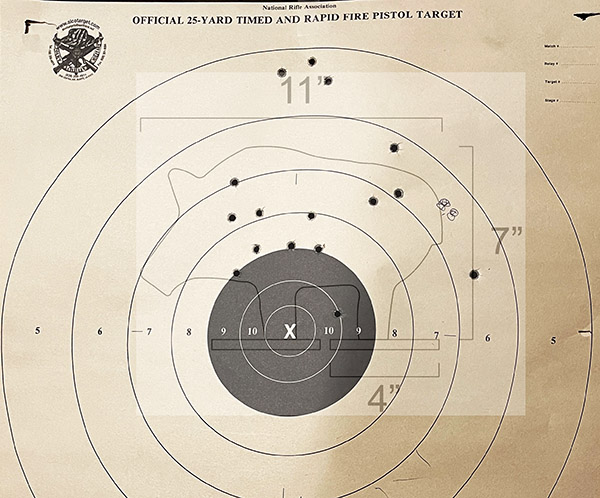

At the range, I set up a couple of targets at 25 yards. I had only loaded 25 rounds, so I shot the first 10 in the Shield. The Shield functioned perfectly with all 10 rounds (I shot two magazines with 5 rounds each). There were no failures to feed or eject. As I had read, the load was accurate (in fact, it was more accurate than anything else I’ve shot before in the Shield). Recoil was very light. I held at 6:00 on a standard 25-yard pistol target; the rounds hit low left (but not as low as I expected). This ain’t half bad with a little belly gun like the Shield. If I needed to, I could slide the Shield’s rear sight to the right to correct for the bias you see below.

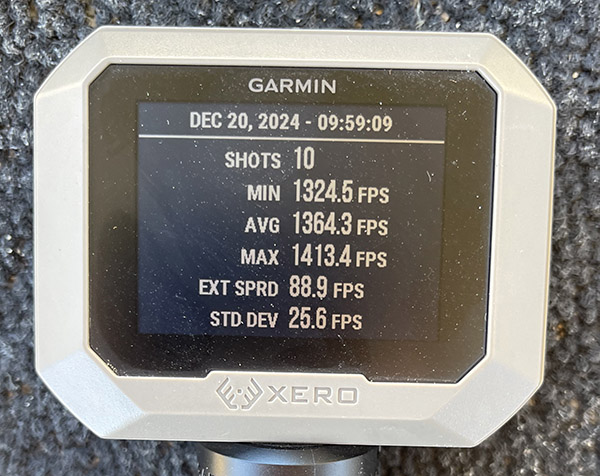

The Shield’s velocities were high, and the standard deviation was low. I am impressed. There are better results than I had previously seen in the Shield.

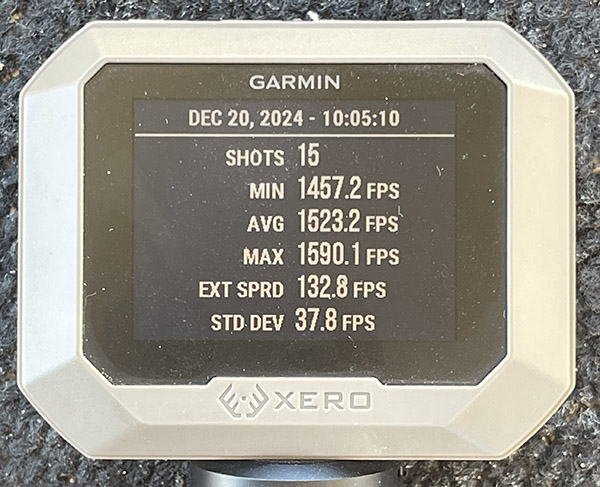

I next fired my remaining 15 rounds in the Springfield 1911. The load was at the top end of what Hodgdon lists for these bullets using HP38 powder (which is the same propellant as Winchester 231).

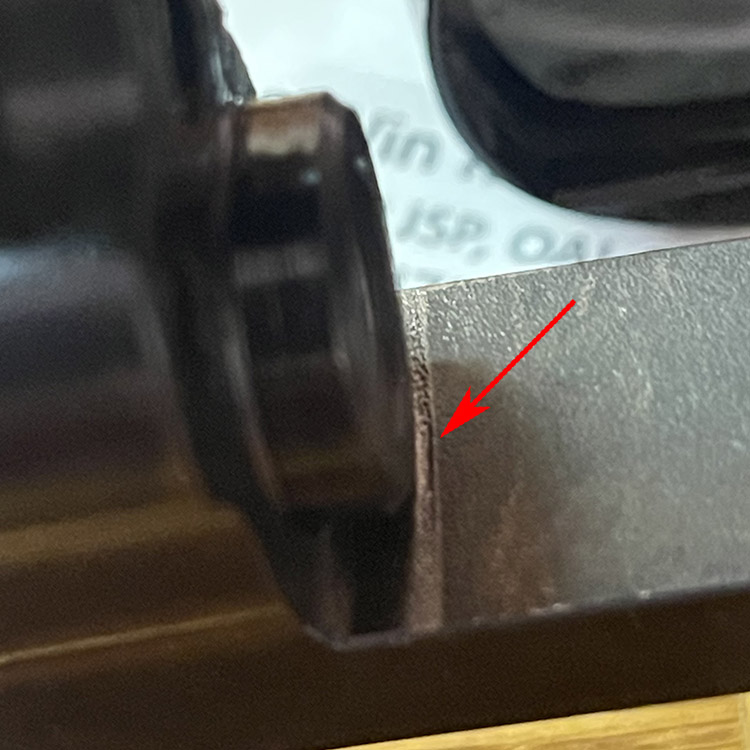

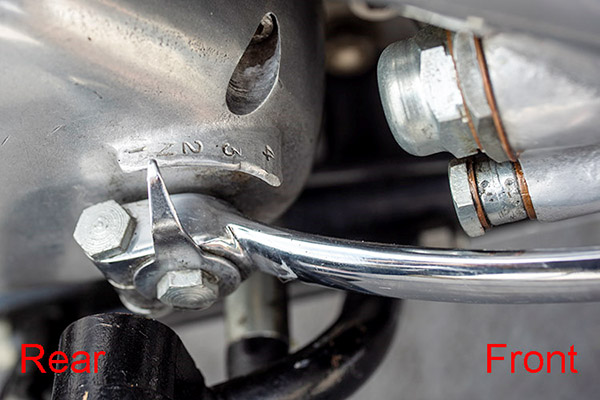

In the 1911, I had one failure to eject. You can see that below.

Also, on the last round for each of the three mags I fired in the Springfield 1911, the pistol did not hold the slide back (it functioned okay for the first four shots). This load apparently has just enough energy to cycle the 1911 slide, but not enough to drive it all the way back. I could probably address this with a lighter recoil spring. Subsequent testing proved to me that the above-described failures were related to how I was holding the 1911 during this test. I used a two-hand hold and I bench rested the pistol on a rest. When I fired with a two-hand hold without bench resting the pistol, it functioned flawlessly.

Here are the chrono results in the 1911. As expected, velocities were higher due to the 1911’s 5-inch barrel. There are other powders will give more velocity with the ARX bullets, but I loaded with what I had on hand. Like Donald Rumsfeld used to say, you go to war with the Army you have.

Like I found with the Shield, the 1911’s accuracy was similarly good at 25 yards (again, with a 6:00 hold on the target). I could probably do better. I didn’t make any sight adjustments, so I was surprised that the gun was pretty much on target.

Another pleasant finding was that the both the Shield and the 1911 dropped the brass right next to the gun. With the 1911, the brass just plopped out and came to rest on the table next to the gun. The Shield dropped most of the brass on the table; three pieces fell off the bench. Where you see the brass in the photo below is where it landed; I didn’t scoop it up and put it there.

The ARX bullets are a little trickier to reload than regular 9mm bullets. Inceptor, the manufacturer, advises against a heavy crimp as it will crush the bullet. The one time I blew up a gun two or three years ago I’m now convinced was the result of bullet setback when feeding due to a light crimp and a slippery powder coated bullet. Setback would be more of a concern here with the light crimp.

I could probably load these bullets a bit hotter to get them to hold the slide back after the last round in the 1911 (or, as mentioned above, go to a lighter spring). I don’t think I want to go above the 5.2 grains of Winchester 231. Also, as noted above, the issue disappeared when I fired normally without bench resting the pistol. This was intended to be a quick look. I learned what I wanted to. The ARX bullets are very good. I ordered a thousand of them, which should last for a while.

Join our Facebook ExNotes page!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: