By Joe Berk

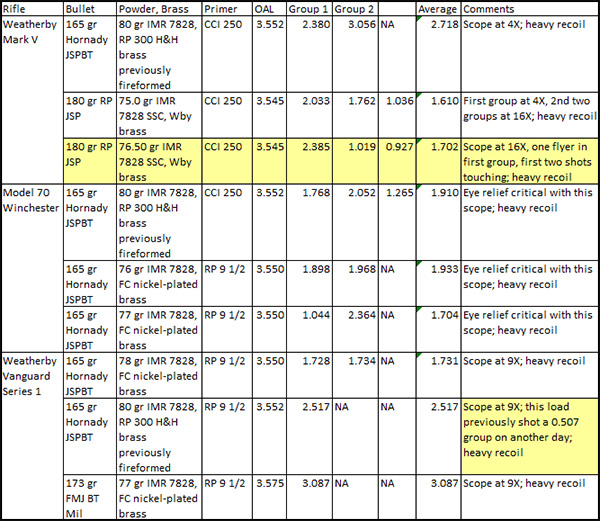

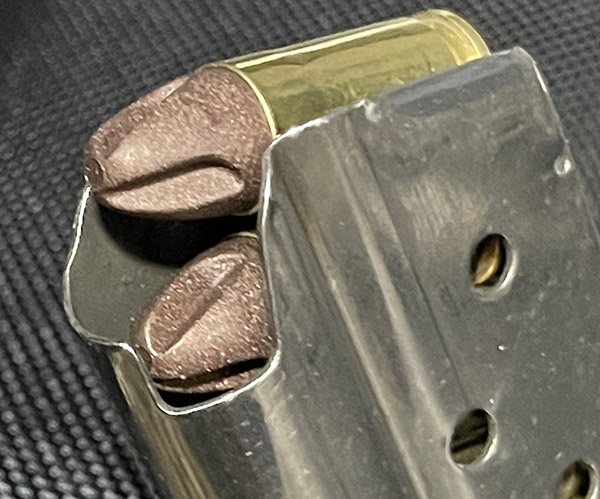

I recently received my order of Inceptor ARX 118-grain .45 ACP bullets. I had previously loaded 9mm ammo with ARX 65-grain bullets and I was pleased with them, so I wanted to try the ARX bullets in the .45, too.

I compared how two 1911s performed on my local indoor pistol range, firing with a two-hand hold (but without a rest) at 10 yards. I used nearly identical 1911 Springfield target pistols, one in 9mm and the other in .45. The .45 1911 is as it came from the factory; this gun has had no custom work done to it other than installing a one-piece guide rod. The 9mm 1911 had the same one-piece guide rod, along with other custom touches by good buddy TJ at TJ’s Custom Gunworks. The 9mm 1911 has a much crisper and lighter trigger, it is an absolute delight to shoot, and it is my favorite handgun.

The ARX bullets are different than anything I’ve used before. They are a mix of copper particles suspended in a polymer matrix. The ARX bullets are much lighter than cast or jacketed bullets, with consequently dramatically higher muzzle velocities. They are not marketed as frangible bullets. They are intended to produce a larger wound cavity and I suppose because of that they could be considered a better defense round. I’m not interested in any of that. I’ll never hunt with either a 9mm or a .45, and although I sometimes carry a 1911 chambered in .45 ACP or my 9mm S&W Shield, when I do so it is always with factory ammunition. Nope, my interested was a result of my buddy Robby gave me a few 9mm ARX bullets and I fell in love with them. The ARX bullets are less expensive than cast or jacketed bullets and they are accurate. For a range rat like me, that’s a good deal.

9mm 1911 ARX Results

I wrote about my initial impressions with the 65-grain 9mm ARX bullets previously (they were all good), so for this first portion of the comparison there’s not too much that’s new other than this load’s attaining 100% reliability in holding the slide back after the last round.

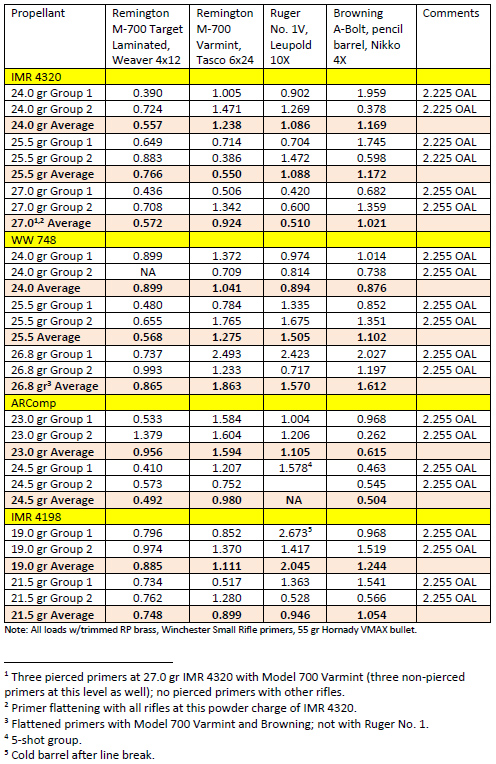

My 9mm load uses 5.2 grains of Winchester’s 231 propellant, with the bullets seated to an overall cartridge length of 1.135 inches. I used CCI 500 primers and mixed brass for the loads you see here (I am lazy and I didn’t want to sort the 9mm brass). I loaded these on my Lee turret press using Lee dies (including the factory crimp die). I took the load data directly from Inceptor’s website. This load is a max load in their standard load listings (i.e., it is below the +P loads the Inceptor data also lists).

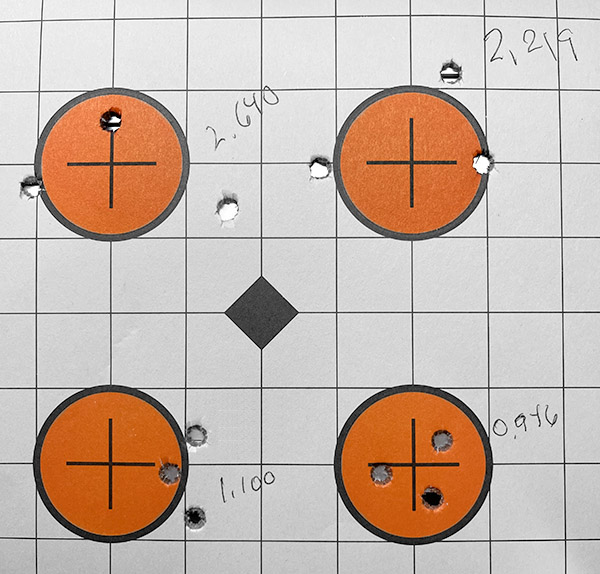

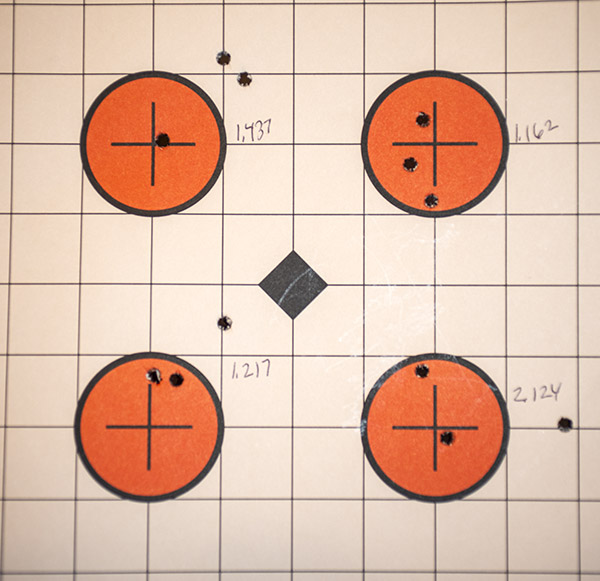

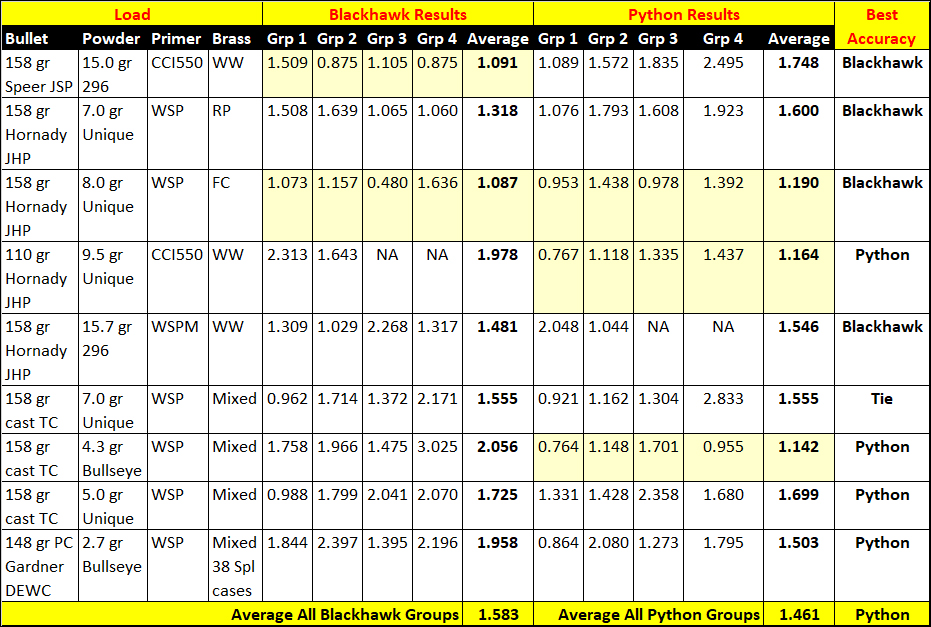

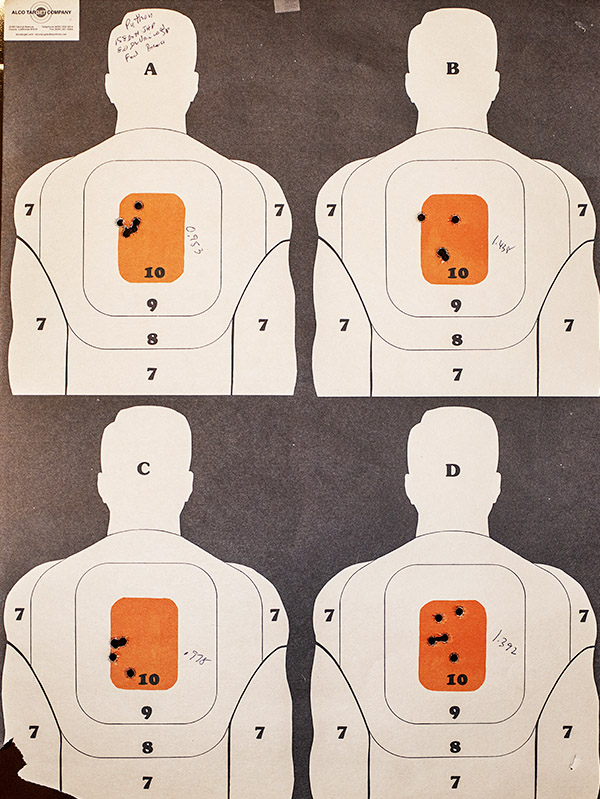

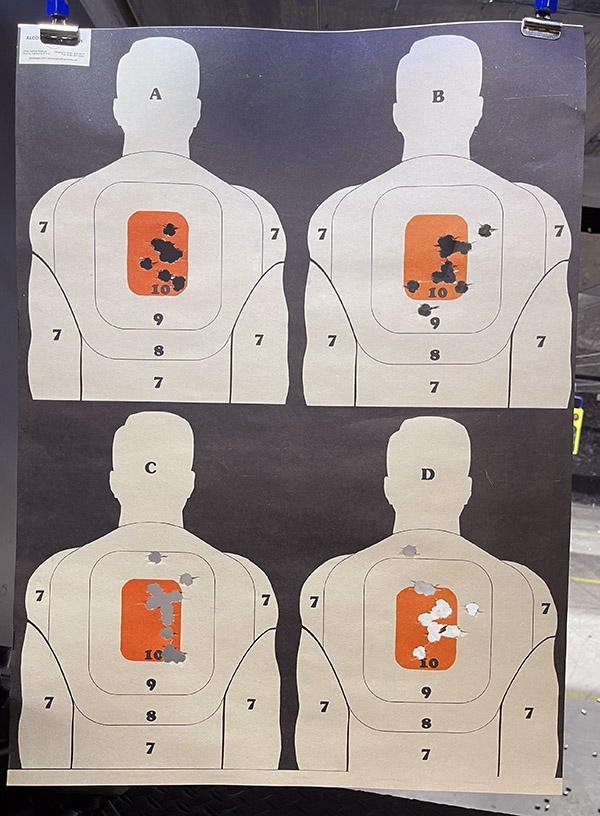

I shot at the Alco four-silhouette target (it has four quarter-sized silhouettes on each sheet), and I sent either 12 or 13 rounds downrange on each silhouette. That made for a total of 50 rounds on each target.

The 9mm ARX load functioned perfectly in my 1911. There were no failures to feed or eject and the pistol stayed open after the last shot fired. This is an accurate load. The flyers are due to yours truly, not the gun or the load. Maybe if I had sorted the brass they would be a little better, but these are good enough for my purposes.

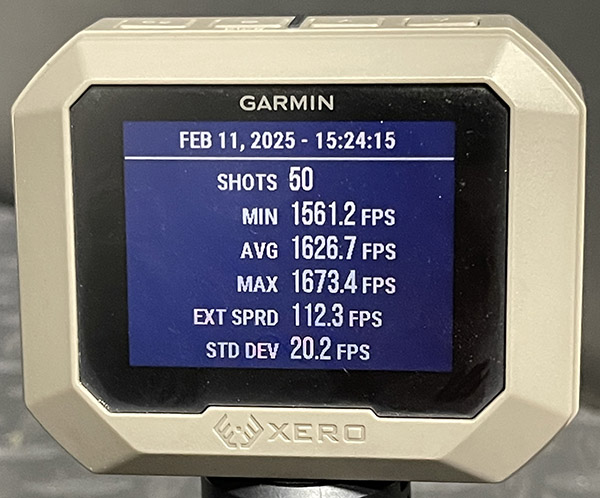

These 9mm bullets only weigh 65 grains. They step out sharply, but the recoil is low (perceptibly lower than what I would feel with a 115 or 124-grain cast or jacketed bullet). Velocities are high for a 9mm (which are typically in the 1100 fps range with cast or jacketed bullets). The Inceptor data for my load showed that they achieved 1433fps with 5.2 grains of HP38 propellant (which is the same powder as Winchester 231). Their results were with a 4-inch barrel. My 1911 has a 5-inch barrel; I achieved an average velocity of 1626fps, or nearly 200fps faster than what Inceptor achieved in their testing. To add a little more context to these findings, I previously tested this load in my S&W Shield (which has a 3.1-inch barrrel). In the Shield, this load averaged 1364fps. The bottom line? My results are consistent with the Inceptor load data.

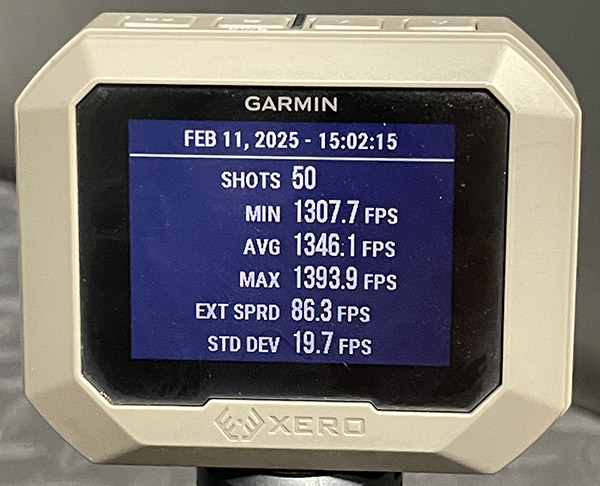

Take a look at the Garmin chrono data for this load in the 1911.

In my prior test of this load in the Springfield 1911 and the S&W Shield, I found that the 1911 would not hold the slide back after the last shot (the Shield didn’t have that problem). In that earlier initial test, I used a two-hand hold and I rested my arms on the bench. I think that might have caused the 1911’s problem with holding the slide open after the last shot. In the range session yesterday, I used a two-hand hold, but I did not rest my arms on the bench (and the gun functioned perfectly, holding the slide open after the last shot on every 5-shot string). The 5.2-grain Winchester 231 load is a good one for the 9mm. It’s accurate, the recoil is light, and reliability is superb.

.45 ACP ARX Bullet Testing

I next moved on to test the 118-grain ARX bullets in my .45 ACP Springfield 1911.

The .45 ACP load used the ARX 118-grain bullet with 9.1 grains of Power Pistol, a Winchester large pistol primer, and Winchester brass, all loaded on the Lee turret press with a Lee crimp die. The .45 ACP load data also came from the Inceptor site. The site lists three powders; the only one I had on hand was Power Pistol. The 9.1 grains of Power Pistol is at the top of their non+P range. It is not a +P load. Ordinarily I would not start testing at the top of the listed propellant weight range, and I probably shouldn’t have done so here (more on that a paragraph or two down).

The Inceptor load recommended a cartridge overall length of 1.26 inches. I loaded with a cartridge overall length of 1.250 inches, which is what I have used in all my other .45 ACP loads. That length fits well in the magazine. I don’t think the additional 1/100 of an inch Inceptor specified would cause interference between the ammo and the forward inside magazine edge, but it’s close and in any event, I wanted to stick with the cartridge length that has always worked for me in the past.

The .45 loads felt hot to me. I think that’s primarily because I have been shooting my 9mm handguns lately. A few of the cartridge cases showed a little (very little) primer flattening. I’m not sure if that was due to firing the round or if it was due to me putting extra effort into primer seating during the reloading process. The .45 ACP is a powerful cartridge, and when I haven’t shot one in a while, it can seem even more powerful.

Accuracy was about the same as with the 9mm. I thought both were good. There were occasional flyers, but that was undoubtedly me and not the gun or the load. Again, I shot offhand for all of these groups, so I wasn’t expecting one-hole results.

Velocities were very much higher than what I’ve seen with other bullets in any .45 ACP. I had previously loaded .45 ACP with all kinds of cast and jacketed bullets ranging from 185-grain wadcutters to 230-grain full metal jacket projectiles. They would typically see velocities of 700fps to maybe 900fps. Some folks load the .45 a little hotter than that with cast or jacketed bullets. I’ve never felt a need to. But those ARX 118-grain bullets! Wow! The Inceptor load data said I would see 1,317fps with 9.1 grains of Power Pistol propellant (and for their .45 ACP testing, Inceptor used a 5-inch barrel); my ammo averaged 1346fps. Extreme spread and standard deviation were low; both extreme spread and standard deviation were similar to what my 9mm ARX loads achieved.

Feed and ejection were flawless in my Springfield 1911. That said, I am going to drop the load down to 8.7 and 8.5 grains of Power Pistol and try that for the next load. If I get good groups and reliable function, that’s where I’ll load in the future.

The Bottom Line

These are good bullets, and I think they represent a huge step forward. They are the first really new thing to come along in the reloading game in a long time.

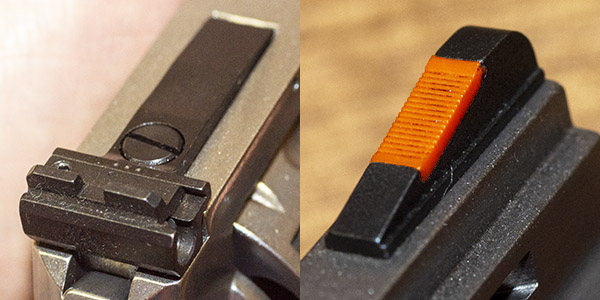

Surprisingly, both the 9mm and the .45 put the bullets where I wanted them, with no sight adjustments from my previous lead or jacketed bullet loads. I expected both the 9mm and .45 ACP ARX loads to shoot low, but they did not. The sights were right on the money.

I didn’t see any copper fouling from the bits of copper mixed in the ARX bullets’ copper/polymer matrix. There’s a tiny bit of blue/purple fouling from the bullet polymer, but it’s very minimal and it’s only in the grooves. I had not cleaned either the 9mm or the .45 1911 after earlier range sessions with cast and plated bullets and the bores were dirty when I started shooting the ARX bullets. Both guns were cleaner after shooting the ARX bullets than they are after shooting cast or jacketed bullets. Bore cleanliness is a big plus here.

Price is another advantage; the 9mm bullets are $57/1000 and the .45 ACP bullets are $65/500 (I think the .45 bullet price at $65/100 is an increase from what I paid a couple of weeks ago). I’ve ordered ARX bullets three times now; on all three orders, they did not charge sales tax. I guess the sales tax is included in the retail price already. Whatever. I’m an anti-tax guy. Whether it’s real or imagined, not paying sales tax is plus in my book.

I’m not going to hunt with either my 9mm or my 1911, but here in California, these bullets should meet our lead-free bullet criteria. Similarly, the bullets are not hollow points. Some places (San Francisco and all of New Jersey come to mind) have outlawed hollow point bullets. These bullets should be okay in places where hollow points are outlawed.

As mentioned near the start of this blog, the drill-bit-like bullet profile creates a much larger wound channel. The idea is that bullet spin allows the bullet to grab onto tissue and propel it outward. There are some YouTube videos that purport to show this in ballistic gelatin. I suppose if you were defending yourself against a bad guy made of ballistic gelatin (think Steve McQueen and the 1958 classic, The Blob) these would be the preferred bullet. None of that matters to me, and from a defense perspective it’s probably moot (especially with the .45). Dead is dead, and with a .45, I’m guessing a larger wound channel won’t make a bad guy any deader. My interest is in how well the ARX bullets shoot on paper, and they do that extremely well.

Join our Facebook ExNotes page!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: