Our last day on the road in Colombia was just a few days before Christmas, and it was a fine ride down from the Volcan Nevado del Ruiz back home to La Ceja. It had been a grand adventure, and I had mixed emotions about it coming to an end. I was looking forward to going home, but I felt bad about wrapping up what had been one of the greatest rides of my life.

Posted on December 22, 2015

Yesterday was our last day on the road. It was yet another glorious day of adventure riding in Colombia.

The night we spent under the Volcan Nevado del Ruiz was freezing. It was the coldest night we experienced on this trip. I had on every layer of clothing I brought with me when we left. Juan told me not to worry, it would warm up as we descended. As always, his prediction was right on the money.

I had mixed emotions as we rolled out that morning. This ride has been one of the great ones, and I am always a little sad on the last day of a major ride because I know it is drawing to a close. But I am also eager to get home. This was a magnificent ride, and it was a physically demanding one. We experienced temperature extremes, from the humid and sultry tropics to the frigid alpine environment we were leaving. The riding was simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying. We road magnificent winding mountain roads, but at times the traffic (especially when we were passing the big 22-wheeled tractor trailer trucks) was unnerving. My neck was sore, most likely from the stress of this kind of riding. But it was grand, and riding Colombia is one of life’s grand adventures.

Juan knows all the good spots in Colombia, and he took us to this one where we could grab a few photos with the volcano steaming in the background.

I had to get a shot of the three of us with the bikes, using the D3300’s self-timer. If we look like three guys (the three amigos) who were having the ride of their lives, well, it’s because we were.

We rode on. We went through towns, we went through the twisties, and we passed more trucks. Another day in Colombia, another few hundred miles. At one point, Juan took us on a very sharp 150-degree right turn and we climbed what appeared to be a paved goat trail. Ah, another one of Juan’s short cuts, I thought. And then we stopped.

“This is Colombia’s major coffee-producing region, and we are on a coffee plantation,” he announced when we took our helmets off. Wow. I half expected Juan Valdez (you know, from the old coffee commercials) to appear, leading his burro laden with only the finest beans. It was amazing. I had never been on a coffee plantation (or even seen a coffee bean before it had been processed), and now here we were. On a coffee plantation. In Colombia. This has been a truly amazing ride.

That big stand of lighter yellowish-green plants you see just left of center in the above photograph is a bamboo grove. More amazing stuff.

These are coffee beans, folks. Real coffee beans.

The beans are picked by hand, Juan explained. It’s very labor-intensive, and these areas are struggling because the world-wide coffee commodities markets are down.

Juan picked a bean and showed me how to peel it open. You can take the inner bean and put it in your mouth like a lozenge (you don’t chew it). To my surprise, it was sweet. It didn’t have even a vague hint of coffee flavor.

As we were taking all of this in, two of Colombia’s finest rolled by.

Juan told me that the police officers in Colombia often ride two up. I had seen that a lot during the last 8 days. Frequently, the guy in back was carrying a large HK 7.62 assault rifle or an Uzi. Colombia is mostly safe today, but that is a fairly recent development.

Vintage cars are a big thing in Colombia. A little further down the road we saw this pristine US Army Jeep for sale. I thought of my good buddy San Marino Bill, who owns a similar restored military Jeep.

Here’s one last shot of yesterday’s ride…it’s the Cauca River valley.

The Andes Mountains enter Colombia from the south, and then split into three Andean ranges running roughly south to north. You can think of this as a fork with three tines. There’s an eastern range of the Andes, a central range, and a western range. The Cauca River (which we rode along for much of yesterday) runs between the western and central Andes. The Magdalena River runs between the central and eastern ranges.

Okay, enough geography…we rolled on toward Medellin (or Medda-jeen, as they say over here) and dropped Carlos off at his home. Juan and I rode on another 40 kilometers to La Ceja (or La Sayza, to pronounce it correctly) to Juan’s home, and folks, that was it. Our Colombian ride was over.

Like I said above, I always have mixed emotions when these rides end. It was indeed a grand adventure, and I don’t mind telling you that I mentally heard the theme from Raiders of the Lost Ark playing in my head more than a few times as we rode through this wonderful place.

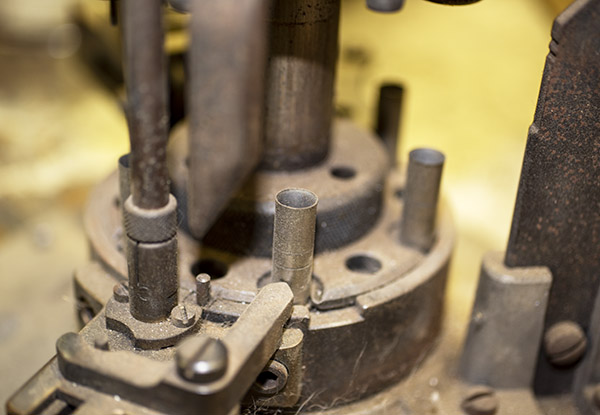

In the next few days, I’ll post more impressions of the trip. In a word, our AKT Moto RX3s performed magnificently. The RX3 is a world-class motorcycle, and anyone who dismisses the bike as a serious adventure riding machine is just flat wrong. I’ve been riding for over 50 years, and this is the best motorcycle for serious world travel I’ve ever ridden. Zongshen hit a home run with the RX3.

I’ll write more about the minor technical distinctions between the AKT and CSC versions of this bike, my experiences with the Tourfella luggage (all good), and more in coming blogs. I’ll tell you a bit about the camera gear I used on this trip, too (a preview…the Nikon D3300 did an awesome job).

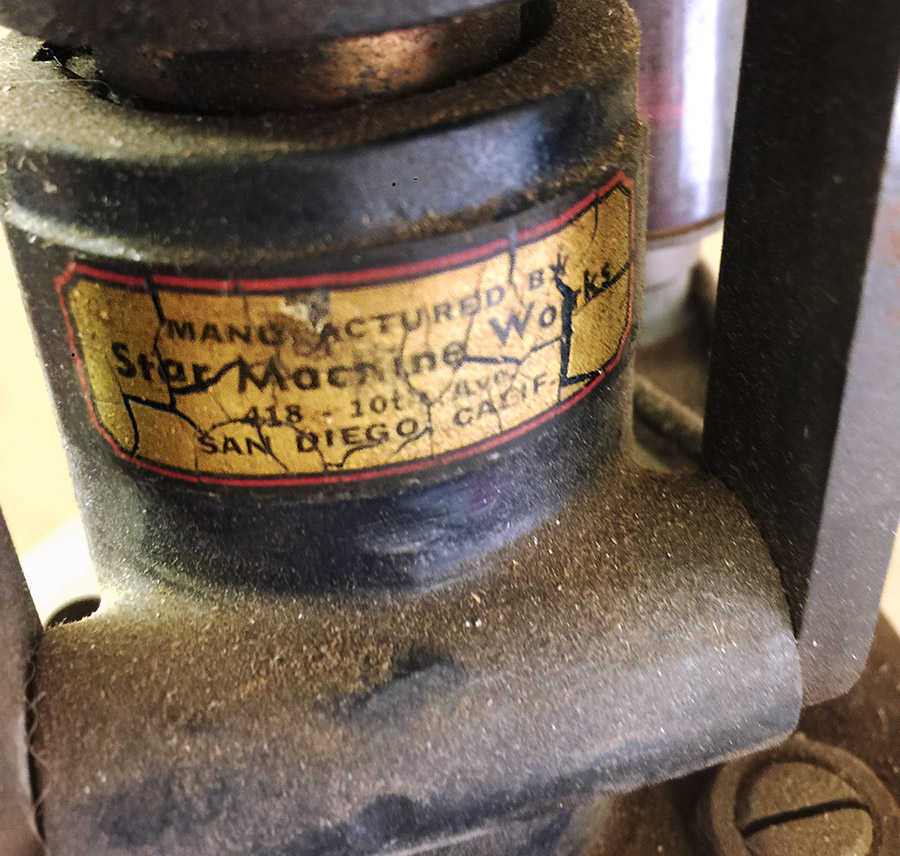

Today I’m visiting with the good folks from AKT Moto to personally thank them for the use of their motorcycle and to see their factory. It’s going to be fun.

More to come, my friends…stay tuned!

Get all of the blogs on Colombia here. If you want to read the book about this ride, pick up a copy of Moto Colombia!

).

).