It was one of Theodore Roosevelt’s favorite rifles, and it was a rifle I’ve wanted for a long time: The 1886 Winchester, except mine isn’t a Winchester. Mine is a Chiappa, and it’s a faithful reproduction of the original 1886 Winchester. After a diligent search, I purchased mine through Gunbroker.com from an outfit in Pennsylvania called Elk County Ammo and Arms and I had it shipped to my favorite local gun shop, Bullet Barn Guns here in southern California.

I picked up my 1886 this week and I was on the rifle range with it the day I did so. It wasn’t my brightest move; it was over a hundred degrees on the firing line and the heat made me woozy by the time I got home. But I wanted to shoot my 1886. Not surprisingly, I was the only nut on the range that afternoon. Also not surprisingly, I enjoyed every second of my 1886 range session. For me, the rifle’s heritage, beauty, performance, accuracy, and general magnificence overcame the heat. Even though old Davy Crockett did his thing a good half century before the Winchester 1886 came on the scene, I kept hearing the music from that old 1950s TV show while I was on the range. You know. Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier and all that. A stunningly-beautiful 1886 and high temperatures will do that do you. King of the Wild Frontier. I liked that. It’s how I felt that afternoon, a feeling fueled by the vintage look and feel of my 1886.

My 1886: Blue Steel and Walnut

Well, not just blue steel and walnut. Blue steel, color case hardened steel, a 26-inch octagonal barrel, and extremely well-figured walnut. It’s a combination that’s tough to beat, especially on a classy lever gun like the 1886.

The folks at Chiappa know what they’re doing. Check out this color case hardening. It’s stunning.

The 1886 and 45 70 Accuracy

So what’s it like shooting the 1886? Hey, take a look…

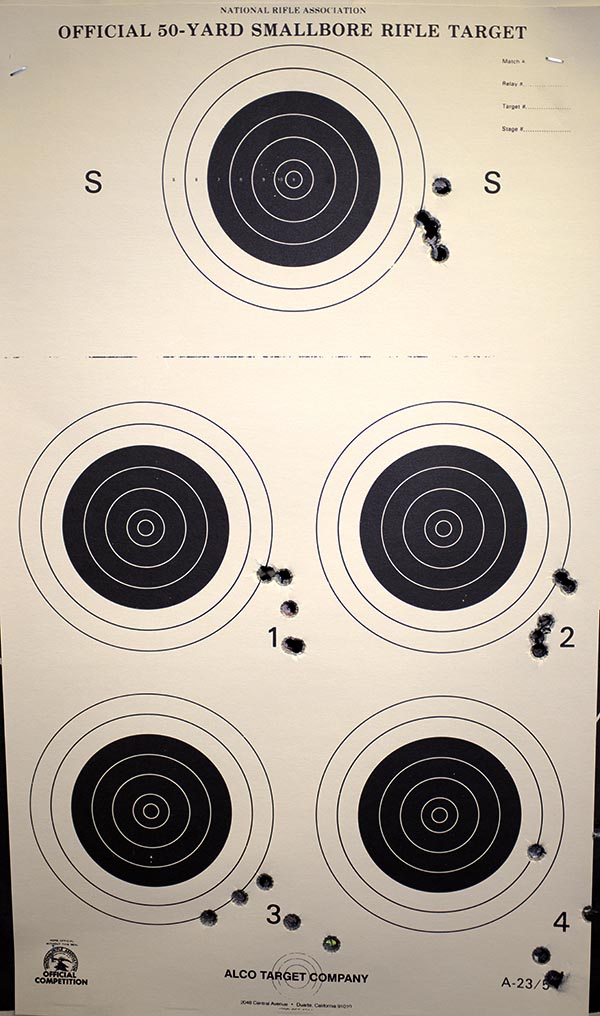

The 1886 Chiappa will shoot. The heat not withstanding, I was having a good time out there. The sun was playing hide-and-seek behind the clouds, and when it went behind the clouds, the difference in accuracy was immediately apparent. I saw firsthand what happens when you have glare on the front sight. When the sun ducked behind the clouds, the front sight stood out clearly. When the clouds moved away and the sun bore down on the 1886 directly, the front sight caught a fair bit of glare. It made getting a clear sight picture difficult, and you can see the results on the target below.

I had my Marlin 45 70 accuracy load (a 405 grain cast bullet with 35.0 grains of IMR 4198 powder) and I used it on the target above. I fired the first three groups with the sun behind the clouds and no front sight glare. Then the clouds shifted, the sun was out in the open, and the front sight started winking at me. Glare kills accuracy when shooting open sights. I proved it. With no front sight glare, the groups were impressive.

The 1886 was shooting to the right, and when I examined the sights, sure enough, the front sight was slightly biased to the left. On a rifle or handgun rear sight, you move the sight in the direction you want the bullets to go (if you want your shots to move to the left, you move the rear sight to the left). On the front sight, it’s just the opposite. You move the front sight in the opposite direction you want the bullets to move.

The front sight on my 1886 needed to move to the right because I wanted to move the shots to the left. I had a gunsmith screwdriver kit with me at the range, but between the heat and my sweating like a stuck pig I didn’t want to fool around trying to move the sights out there. I thought it would be best to wait until I returned home and do it in my shop. That’s what I did, and I’m eager to get back out on the range and try it again.

45 70 Recoil

In the video above, the 1886’s recoil looks to be pretty mild, and it was for the three shots you see me firing in the YouTube (I was shooting a light Trail Boss load). I brought two different loads with me to the range. One was the aforementioned light Trail Boss load; the other was the more serious IMR 4198 load that I also mentioned earlier. Trail Boss and IMR 4198 are two different propellants; Trail Boss loads generally give low bullet velocity and low recoil (you know, it’s the old f = ma thing). IMR 4198 makes the bullet step out more earnestly and that load used a heavier bullet. Both resulted in a sharp step up in recoil.

With the light Trail Boss load and a 300-grain Hornady jacketed hollow point bullet, the recoil was tolerable (as you can see in the video). With my accuracy load (the one I developed for my 45 70 Marlin, a 405-grain cast bullet and 35 grains of 4198), the steel 1886 buttplate hurts big time. I had to use a wadded up T-shirt as a half-assed recoil pad for a field expedient. But the rifle will shoot. It’s accurate, as the above groups show.

The Gunstores

As I mentioned above, I bought my Chiappa 1886 from Elk County Ammo and Arms in Pennsylvania. There are a lot of shops selling the 1886 Chiappa, but Elk County Ammo and Arms was the only one willing to take photos of my rifle and email them to me so I could see what I was getting. That was a big plus for me, and it cinched the deal once I saw the actual rifle. I had Elk County Ammo and Arms ship the rifle to my local gun store, Bullet Barn Guns, here in southern California. Bullet Barn Guns is a family-run operation and they are absolutely top notch in every regard. Like me, they appreciate blue steel and fine walnut, and they were blown away by my 1886 when it arrived (so much so that they shot photos of it and emailed them to me, too). The folks at Bullet Barn are enthusiasts, just like me.

The 1886 Chiappa: The Bottom Line

I’m a happy camper. I wanted an 1886 with good wood and this one answered the mail. The walnut is stunning. The checkering is hand cut and sharp (it’s not laser cut or pressed, as is the case on many rifles today). The walnut is oil finished, which makes it easily repairable when the inevitable hunting, range, and general use scratches occur. The metal work is superior (you can see that in the above photos). The trigger is good (there is no creep). And the rifle is accurate. It groups well. After I shot the above target, I used up the remainder of the box of ammo I brought to the range shooting at a rock out at about 150 yards, and I connected every time. That was cool.

About the only thing I don’t care for is that the lever does not lay flush against the receiver; it’s angled out a degree or two. I don’t think that’s a big deal, but I had to find something to bitch about (I’m told it’s part of my charm). That’s it.

The bottom line is that the Chiappa 1886 is a beautiful and accurate rifle. I had wanted an 1886 with nice wood and color case hardening for a long time, and now I have one. Keep an eye on the ExNotes blog, folks. This is a rifle that will be back on these pages.

Like stuff on blue steel and walnut, or maybe the 45 70 cartridge? Hey, check out our Tales of the Gun page!

The original finish had a lot of scratches and dings; those are all gone. The 340 originally had white line spacers between the buttplate and the stock, and between the pistol grip cap and the stock. I like the “less is more” look (I think it’s more elegant), and I think I achieved it by deleting the spacers. The rifle’s original finish was some sort of shellac or varnish that gave a reddish hue to the stock; the new

The original finish had a lot of scratches and dings; those are all gone. The 340 originally had white line spacers between the buttplate and the stock, and between the pistol grip cap and the stock. I like the “less is more” look (I think it’s more elegant), and I think I achieved it by deleting the spacers. The rifle’s original finish was some sort of shellac or varnish that gave a reddish hue to the stock; the new  I was able to hook up

I was able to hook up  The

The

Applying the

Applying the  I applied a thin fourth coat of

I applied a thin fourth coat of