When I first opened the packing on the Go-Bowen mini bike I was impressed by the quality look of the little green monster. That first impression has taken a bit of a hit as I ran into quality control issues with the Go-Bowen

mostly relating to the back wheel. (So far, that is.)

The little mini came from the factory with the chain adjusted ridiculously tight. The mini would hardly roll. I loosened axle and took a few turns off the nicely made chain adjusters and all seemed well. I drained the factory engine oil and replaced it with a high grade of store brand stuff and dumped a few ounces of fuel into the gas tank.

Starting the mini was very easy. There is a primer bulb under the carburetor and a few semi-erotic squeezes later I could see the fuel flow into the clear gas lines. A bit of choke, a few easy pulls and the mini was running like it was made to run. For only 1.4 horsepower the mini has a get-go feeling. The idle was set high so I took a few turns off the idle screw. I took a hot lap of Tinfiny’s upper reaches when the chain flew off.

This was odd because I didn’t loosen the thing all that much. I pushed it back to the shop and had a look see. Turns out the axle adjusting slots are not indexed the same and to center the rear wheel in the frame you end up with the axle cocked in the adjusters.

Once I had the chain running true I noticed the rear brake caliper wiggling alarmingly. A severely wobbling disc rotor caused that problem. The thing is like 3/16” out of true. It looks as if the flange is machined wrong or the disc itself is bent. I haven’t gone any further into the disc problem yet.

The mini rides fine once you get the chain to stay on and if the thing had any more power you’d probably flip over backwards. There is a heck of a lot of noise coming from the primary chain housing so I’ll have to look inside to see what gives.

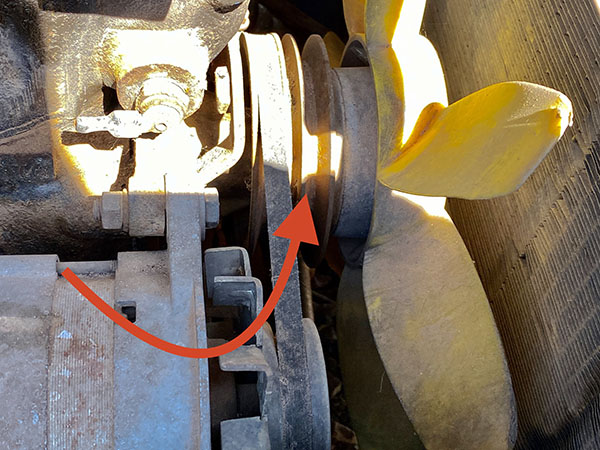

The exhaust pipe on the Go-Bowen exits directly on the rear brake cable. I will need to rig some sort of turn out to redirect the hot gasses but for now I slipped a short piece of silicone heat shielding over the cable for protection.

It was a disappointing first run with the Go-Bowen. I will work on the disc and the noisy primary situation when I get time. Even with the issues the mini still seems like it’s worth the $299 with shipping included but you’ll need to budget a few hours going over the set up fixing shoddy assembly from the factory before any long distance travel is attempted. It’s like they built a nice mini bike then had their stupidest employees assemble the thing. More will be forthcoming after repairs when I get a chance to road test the mini in true ExhaustNotes.us fashion.

See all our product reviews here!

Join the ExNotes platoon for free!

Gresh’s most recent blog (

Gresh’s most recent blog (

).

).