My good buddy Joe Gresh is an astute observer of the human condition and he writes about it well. This is a piece he did after the 5,000-mile Western America Adventure Ride, when we rode 250cc Chinese motorcycles from LA to Sturgis to Portland and back to LA. We had about a dozen riders and not a single motorcycle breakdown. The bikes’ stellar performance notwithstanding, we sure caught flak on the Internet about riding Chinese bikes (and it was only on the Internet; no one we met in person had anything but compliments for us and the bikes). Joe wrote a column titled “Motoracism” in the now-defunct Motorcyclist magazine about that trip (along with an outstanding story about the ride). Joe’s adept at stirring the pot by telling the truth, and the keyboard commandos crawled out in droves from under their bridges when “Motoracism” was published. Here’s the original article. Take a look…

Motoracism and Brand-Bashing in the Moto World

Are you offended by a Chinese-built bike?

Joe Gresh January 11, 2016

Look out! An army of strange bikes aimed at our heartland! Or is it just a line of motorcycles like any other, except this time they’re made in China?

We all suffer from racism’s influence. It’s an off-key loop playing from an early age, a low frequency rumble of dislike for the “other.” It’s ancient and tribal, a rotted pet forever scratching at the door because we keep tossing it scraps of our fear. Racism gives the weak succor and the strong an excuse for bad behavior. We work hard to become less racist, but exclusion is a powerful medicine.

Especially when it comes to motorcycles. Brand bashing is ancient, part of what motorcyclists do. It’s our way of hazing new riders and pointing out the absurdity of our own transportation choice. Unlike more virulent forms of racism, motoracism doesn’t prevent us from enjoying each other’s company or even becoming friends.

In web life, we are much less tolerant. Whenever I test a bike for Motorcyclist I spend time lurking on motorcycle forums. This is partly to gather owner-generated data, stuff I may miss in the short time I have with a testbike. Mostly I do it because it’s a way to rack up thousands of surrogate road test miles without having to actually ride the bike. Think of yourselves as unpaid interns slogging through the hard work of living with your motorcycle choice while I skim the cream of your observations into my Batdorf & Bronson coffee.

Every motorcycle brand has fans and detractors, and I enjoy the smack talk among riders. Check out the rekindled Indian/Harley-Davidson rivalry: They picked up right where they left off in 1953. Then there’s this Chinese-built Zongshen (CSC) RX3 I recently rode. Man, what a reaction that one got. Along with generally favorable opinions from Zong owners I saw lots of irrational anger over this motorcycle.

All because it was built in China.

To give the motoracists their due, until Zongshen came along Chinese-built bikes were pretty much crap. (I read that on the Internet.) Except for the Chinese-built bikes rebadged for the major manufacturers. I guess if you don’t know that your engine and suspension were built in China it won’t hurt you.

Mirroring traditional racism, the more successful the Chinese become at building motorcycles the more motoracists feel aggrieved. The modest goodness of the Zongshen has caused motoracists to redirect their ire at US/China trade relations, our looming military conflict in the South China Sea, and working conditions on the Chinese mainland.

Like Japanese motorcycles in the 1960s, buying a Chinese motorcycle today reflects poorly on your patriotism. You’ll be accused of condoning child slavery or helping to sling shovelfuls of kittens into the furnaces of sinister ChiCom factories. Participate in a Zongshen forum discussion long enough and someone inevitably asks why you hate America. I’ve had Facebook friends tell me I shouldn’t post information about the Zongshen—that I must be on their payroll. I’m just testing a bike, man. This reaction doesn’t happen with any other brand and they all pay me the same amount: zilch.

So if you’re angry about working conditions in a Chinese motorcycle factory, but not about similar conditions in a USA-based Amazon fulfillment warehouse (selling mostly Chinese products) you might be a motoracist. If you type moral outrage on your Chinese-built computer complaining about China’s poor quality control while sitting in your Chinese-built chair and answering your Chinese-built cell phone you might be a motoracist. If you’re outraged that the Zongshen 250 can’t match the performance of a motorcycle five times its displacement and five times its cost you might be a motoracist. I want you to take a thoughtful moment and ask yourself if your motoracism isn’t just plain old racism hiding behind mechanical toys. If it is, stop doing it, and let’s get back to bashing other motorcycles for the right reasons: the goofy jerks who ride them.

Good stuff, and great writing. If you’d like to read Joe’s piece about the ride, just click here. And if you’d like to know more about the RX3 motorcycles we rode on our ride through the American West, just click here.

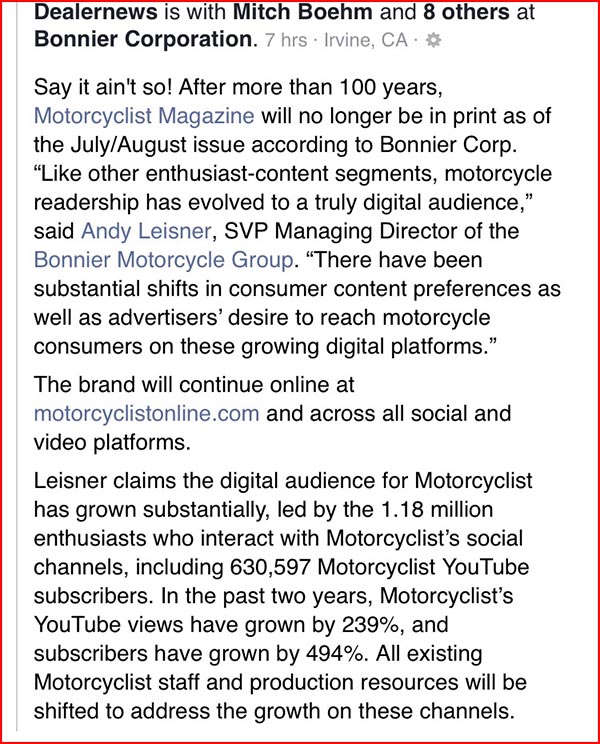

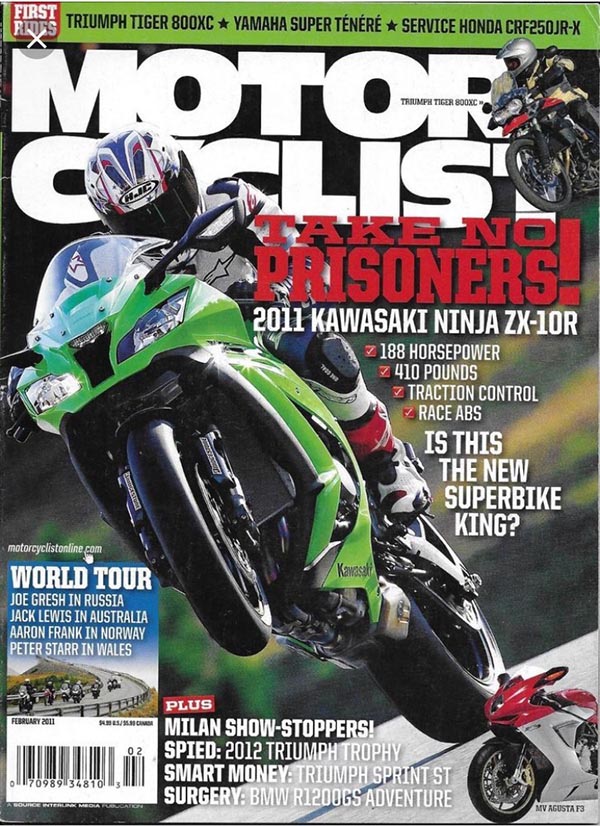

The distance from being read in the crapper and actually being in the crapper is a short one. According to Dealer News, Motorcyclist magazine crossed that span this week. I’m not happy about it. In fact, I’m well pissed-off. Over 100 years of print publication down the tubes. I was a part of that glorious history for 10 years. MC mag was always my favorite. They had Burns, they had Boehm, they had Frank and they had that crazy kid that kept crashing GSXR’s. MC mag was way cooler and funnier than stodgy old corporate-Cycle World. When I first decided to submit motorcycle stories for publication MC mag was the only place I submitted to.

The distance from being read in the crapper and actually being in the crapper is a short one. According to Dealer News, Motorcyclist magazine crossed that span this week. I’m not happy about it. In fact, I’m well pissed-off. Over 100 years of print publication down the tubes. I was a part of that glorious history for 10 years. MC mag was always my favorite. They had Burns, they had Boehm, they had Frank and they had that crazy kid that kept crashing GSXR’s. MC mag was way cooler and funnier than stodgy old corporate-Cycle World. When I first decided to submit motorcycle stories for publication MC mag was the only place I submitted to. Bonnier bought most of the USA’s larger motorcycle magazines a few years back and instead of finding a way they have shuttered magazine after magazine. They’ve managed to turn the largest motorcycle enthusiast’s print group into a damn Internet blog. What a stunning waste of money. Bonnier is supposed to be the experts. The much-touted single-source vertical integration has become a major horizontal screw-up. Thanks guys. Thanks for screwing up nearly everything I liked about your books.

Bonnier bought most of the USA’s larger motorcycle magazines a few years back and instead of finding a way they have shuttered magazine after magazine. They’ve managed to turn the largest motorcycle enthusiast’s print group into a damn Internet blog. What a stunning waste of money. Bonnier is supposed to be the experts. The much-touted single-source vertical integration has become a major horizontal screw-up. Thanks guys. Thanks for screwing up nearly everything I liked about your books. Bonnier’s press release tries to spin the magazine’s closure in the best possible light citing MC’s huge social media reach. Most of those puffy numbers are a direct result of Brian Hatano’s work years ago and Ari/Zack’s well done YouTube channel. Anyway, as Berk and I have learned, Facebook friends do not equal views. When a page with a million-plus followers puts up an interesting post and gets two comments, I’m telling you the reach is just not there. I get more response from a post about adobe blocks.

Bonnier’s press release tries to spin the magazine’s closure in the best possible light citing MC’s huge social media reach. Most of those puffy numbers are a direct result of Brian Hatano’s work years ago and Ari/Zack’s well done YouTube channel. Anyway, as Berk and I have learned, Facebook friends do not equal views. When a page with a million-plus followers puts up an interesting post and gets two comments, I’m telling you the reach is just not there. I get more response from a post about adobe blocks. It takes 60 shovelfuls to fill the adobe mixer. Originally designed for mortar, the outside drum of our mixer looks like an inverted lunar landscape. Dimples as large as a quarter, back when a quarter was worth 25 cents, protrude far enough to run afoul of the mixer’s I-beam chassis. It’s the rocks, see? Mixing adobe eats up the rubber wiper blades on the paddles and as the gap between the blade and the drum grows larger things start going south. When the gap grows large enough the mixer paddles wedge into the rocks and a sharp pop, like someone hit the machine with a 16-pound sledgehammer, is followed by a lurch of the heavy machine. Another dimple has been created. If the conditions are just right the mixer blades will lock up solid and it takes a quick hand on the clutch lever to prevent a smoking V-belt.

It takes 60 shovelfuls to fill the adobe mixer. Originally designed for mortar, the outside drum of our mixer looks like an inverted lunar landscape. Dimples as large as a quarter, back when a quarter was worth 25 cents, protrude far enough to run afoul of the mixer’s I-beam chassis. It’s the rocks, see? Mixing adobe eats up the rubber wiper blades on the paddles and as the gap between the blade and the drum grows larger things start going south. When the gap grows large enough the mixer paddles wedge into the rocks and a sharp pop, like someone hit the machine with a 16-pound sledgehammer, is followed by a lurch of the heavy machine. Another dimple has been created. If the conditions are just right the mixer blades will lock up solid and it takes a quick hand on the clutch lever to prevent a smoking V-belt. With adobe mixing the show must go on so Pappy and I work in silence. Not total silence though, because we have to keep count of how many shovels we are throwing into the hopper. “I’m at 13,” I tell Pappy. “15” for me, Pappy replies. The mixer locks up, I grab the clutch. We move loaded buggies to the block-making area then we shovel more dirt into the hopper. Soon the injury is forgotten. “Is that good?” “More water.” Pappy says. “4 more shovelfuls.” “Ok, that’s good. Let’s let it mix” Pappy feels bad about yelling at me, I feel bad for hurting Pappy. We are a team again. I’ve got to be more careful working around others.

With adobe mixing the show must go on so Pappy and I work in silence. Not total silence though, because we have to keep count of how many shovels we are throwing into the hopper. “I’m at 13,” I tell Pappy. “15” for me, Pappy replies. The mixer locks up, I grab the clutch. We move loaded buggies to the block-making area then we shovel more dirt into the hopper. Soon the injury is forgotten. “Is that good?” “More water.” Pappy says. “4 more shovelfuls.” “Ok, that’s good. Let’s let it mix” Pappy feels bad about yelling at me, I feel bad for hurting Pappy. We are a team again. I’ve got to be more careful working around others. “Who wants to give it a try?” Pat asks and several would-be adobe builders jump in and start laying blocks. Instead of cement mortar, more mud is used to set the Adobe blocks. I’m cutting a bevel into the blocks to create a space for small volcanic rocks. The rocks are fitted into the bevels and held in with a white lime mortar. Once these protruding rocks are set the lime plaster will adhere to the rocks, hopefully keeping the plaster from sloughing off the wall.

“Who wants to give it a try?” Pat asks and several would-be adobe builders jump in and start laying blocks. Instead of cement mortar, more mud is used to set the Adobe blocks. I’m cutting a bevel into the blocks to create a space for small volcanic rocks. The rocks are fitted into the bevels and held in with a white lime mortar. Once these protruding rocks are set the lime plaster will adhere to the rocks, hopefully keeping the plaster from sloughing off the wall. There’s another, even older method of finishing adobe walls borne from necessity: More mud. Mud plaster doesn’t last as long as lime plaster but if you don’t have lime what’s a poor boy to do? Think of mud plaster as a sacrificial coating. It erodes so that the adobe blocks underneath don’t. Mud plaster is applied by hand or trowel, and re-applied every few years as needed. As Pat’s students, we got to try all application methods with special emphasis on the difficult ones.

There’s another, even older method of finishing adobe walls borne from necessity: More mud. Mud plaster doesn’t last as long as lime plaster but if you don’t have lime what’s a poor boy to do? Think of mud plaster as a sacrificial coating. It erodes so that the adobe blocks underneath don’t. Mud plaster is applied by hand or trowel, and re-applied every few years as needed. As Pat’s students, we got to try all application methods with special emphasis on the difficult ones. In San Diego I lived across the street from a Safeway food market. Man, I never ran out of anything. That Safeway is now a West Marine boat supply store. They got nothing to eat in the whole damn place. But back then, around 1980, it was a great food source.

In San Diego I lived across the street from a Safeway food market. Man, I never ran out of anything. That Safeway is now a West Marine boat supply store. They got nothing to eat in the whole damn place. But back then, around 1980, it was a great food source. The only camera that survived our 40-day, Zongshen RX3 China tour was the one inside my cell phone. My Canon 5D, that weighs a ton, broke its battery door and the 28-135 zoom lens actually fractured and stopped zooming. It sounds like the gears inside are broken. Both were inside a padded camera bag and the bag was wrapped in extra clothing. Don’t let anyone tell you we didn’t pound on those Zongshen RX3’s.

The only camera that survived our 40-day, Zongshen RX3 China tour was the one inside my cell phone. My Canon 5D, that weighs a ton, broke its battery door and the 28-135 zoom lens actually fractured and stopped zooming. It sounds like the gears inside are broken. Both were inside a padded camera bag and the bag was wrapped in extra clothing. Don’t let anyone tell you we didn’t pound on those Zongshen RX3’s. My go-to travel camera, a little Canon S95, also could not survive the rough Chinese trails we explored. The S95 suffered a broken screen and refused to boot up due to a broken top plate. Again, this camera was in my jacket pocket and not rattling around in a bag. We ride hard, you know?

My go-to travel camera, a little Canon S95, also could not survive the rough Chinese trails we explored. The S95 suffered a broken screen and refused to boot up due to a broken top plate. Again, this camera was in my jacket pocket and not rattling around in a bag. We ride hard, you know? Here you can see the extra bit of zoom. S100 on left.

Here you can see the extra bit of zoom. S100 on left. I researched the camera forums and found some S100 owners never have the lens error and of those that did a ribbon wire falling out of its socket was the cause for most of the failures. So I bit on a sweet 100-dollar, S100 that looks like brand new and seems to function perfectly.

I researched the camera forums and found some S100 owners never have the lens error and of those that did a ribbon wire falling out of its socket was the cause for most of the failures. So I bit on a sweet 100-dollar, S100 that looks like brand new and seems to function perfectly. The S100 boots up noticeably faster than the S95 but I am never in that much of a hurry. It will burst a bunch of shots faster than the old model. This may come in handy for action shots. The wide-angle lens is only noticeable when comparing both cameras side by side. When it comes to photography, more is always better. I’m happy with the little S100 and can’t wait to try it out on a motorcycle trip. If I ever go on another motorcycle trip, that is.

The S100 boots up noticeably faster than the S95 but I am never in that much of a hurry. It will burst a bunch of shots faster than the old model. This may come in handy for action shots. The wide-angle lens is only noticeable when comparing both cameras side by side. When it comes to photography, more is always better. I’m happy with the little S100 and can’t wait to try it out on a motorcycle trip. If I ever go on another motorcycle trip, that is. Here at ExhaustNotes.us we are all about the motorcycle, with a smattering of gunplay and interesting adventure destinations thrown in to keep the place hopping. But what if there were no bikes, adventures or bullets? What then? Keep reading and I’ll tell you what then, Bubba.

Here at ExhaustNotes.us we are all about the motorcycle, with a smattering of gunplay and interesting adventure destinations thrown in to keep the place hopping. But what if there were no bikes, adventures or bullets? What then? Keep reading and I’ll tell you what then, Bubba. Situated in the steep-ish foothills of the Sacramento Mountains, Tinfiny Ranch is slowly bleeding into the arroyo, you know? You put down your cold, frosty beer and the next thing you know your Stella is halfway to White Sands National Monument. On the lee side of The Carriage House we’ve lost a good 18-inches of mother earth because while it doesn’t rain often in New Mexico when it does rain it comes down in buckets. This sudden influx of water tears through Tinfiny Ranch like freshly woken kittens and sweeps everything in its path down, down, down, into the arroyo and from there on to the wide, Tularosa Valley 7 miles and 1500 feet below. Claiming dominion over the land is not as easy as they make it sound.

Situated in the steep-ish foothills of the Sacramento Mountains, Tinfiny Ranch is slowly bleeding into the arroyo, you know? You put down your cold, frosty beer and the next thing you know your Stella is halfway to White Sands National Monument. On the lee side of The Carriage House we’ve lost a good 18-inches of mother earth because while it doesn’t rain often in New Mexico when it does rain it comes down in buckets. This sudden influx of water tears through Tinfiny Ranch like freshly woken kittens and sweeps everything in its path down, down, down, into the arroyo and from there on to the wide, Tularosa Valley 7 miles and 1500 feet below. Claiming dominion over the land is not as easy as they make it sound. After the wall is up the resulting divot will require filling with dirt. I have lots of dirt on Tinfiny Ranch; the conundrum is where to borrow it from without causing even more erosion. I’m hoping that leveling the back yard will provide most of the needed fill.

After the wall is up the resulting divot will require filling with dirt. I have lots of dirt on Tinfiny Ranch; the conundrum is where to borrow it from without causing even more erosion. I’m hoping that leveling the back yard will provide most of the needed fill.

Most all of the fun things we did as little kids were instigated by my Grandparents. Between raising four kids and working constantly to pay for the opportunity our parents were left spent, angry and not that into family-time trips. We did try it a few times but it seems like the trips always ended with someone crying, my parents arguing or a small child missing an arm. With only 16 limbs between us we had to be careful and husband our togetherness for fear of running out.

Most all of the fun things we did as little kids were instigated by my Grandparents. Between raising four kids and working constantly to pay for the opportunity our parents were left spent, angry and not that into family-time trips. We did try it a few times but it seems like the trips always ended with someone crying, my parents arguing or a small child missing an arm. With only 16 limbs between us we had to be careful and husband our togetherness for fear of running out. We always bought infield tickets. Camping at the Daytona Speedway was included with infield tickets so we immersed ourselves in the racing and never had to leave. Gramps had a late 1960’s Ford window van with a 6-cylinder, 3-on-the-tree drivetrain. The van was fitted out inside with a bed and had a table that pivoted off the forward-most side door. To give us a better view of the racing Gramps built a roof rack out of 1” tubing. The rack had a ¾” plywood floor and was accessed via a removable ladder that hung from the rack over the right rear bumper.

We always bought infield tickets. Camping at the Daytona Speedway was included with infield tickets so we immersed ourselves in the racing and never had to leave. Gramps had a late 1960’s Ford window van with a 6-cylinder, 3-on-the-tree drivetrain. The van was fitted out inside with a bed and had a table that pivoted off the forward-most side door. To give us a better view of the racing Gramps built a roof rack out of 1” tubing. The rack had a ¾” plywood floor and was accessed via a removable ladder that hung from the rack over the right rear bumper. When you would climb the ladder to the upper deck your hands would pick up silver paint. If you sat on the deck your pants would turn silver. If you rubbed your nose like little kids do your nose would turn silver. It was like Gramps painted the deck with Never-Seez. After a full day of racing we looked like little wads of Reynolds Wrap.

When you would climb the ladder to the upper deck your hands would pick up silver paint. If you sat on the deck your pants would turn silver. If you rubbed your nose like little kids do your nose would turn silver. It was like Gramps painted the deck with Never-Seez. After a full day of racing we looked like little wads of Reynolds Wrap. Our camp stove was a two-burner alcohol fueled unit that, incomprehensibly, used a glass jar to contain the alcohol. Even to my 10 year-old eyes the thing looked like a ticking time bomb so I kept my distance while gramps lit matches and cussed at the stove.

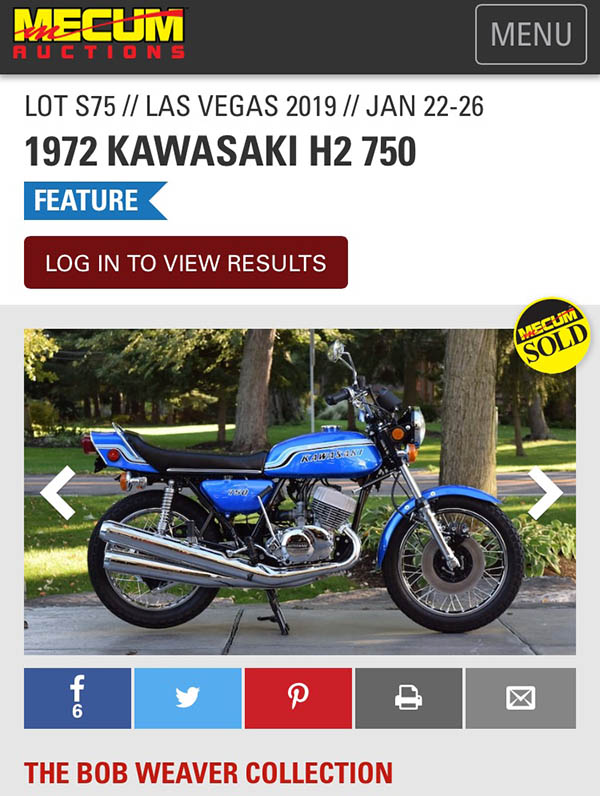

Our camp stove was a two-burner alcohol fueled unit that, incomprehensibly, used a glass jar to contain the alcohol. Even to my 10 year-old eyes the thing looked like a ticking time bomb so I kept my distance while gramps lit matches and cussed at the stove. In all passions you will find lovers and users. The vintage motorcycle passion, looking backwards towards a rose-tinted youth seems to have more than its share of both. Most vintage motorcycle enthusiasts are into the hobby because they either had a particular model or dreamed of owning a particular model way back when they were freshly weaned from the teat of childhood. Powerful first impressions drill that Yamaha RT1 or Kawasaki Z1B into a youngster’s brain like the clean, soapy scent of their first girlfriend’s hair.

In all passions you will find lovers and users. The vintage motorcycle passion, looking backwards towards a rose-tinted youth seems to have more than its share of both. Most vintage motorcycle enthusiasts are into the hobby because they either had a particular model or dreamed of owning a particular model way back when they were freshly weaned from the teat of childhood. Powerful first impressions drill that Yamaha RT1 or Kawasaki Z1B into a youngster’s brain like the clean, soapy scent of their first girlfriend’s hair. Motorcycle road racing in America has not met expectations for quite a while now. Our guys are no longer dominating GP racing as they did in decades past. MotoAmerica, our premier road racing league has made strides by reinstalling the 1000cc bikes as the premier class and bumping the 600’s down to B-team. Hiring my Internet-buddy Andrew Capone as rainmaker for the series is another great move towards professional sponsorship and revenue generation. I’ve never raced on pavement but I rank as an expert spectator due to the sheer number of road races I’ve attended. I’ve got a few ideas on how to make MotoAmerica better and I’m not shy about cranking them out.

Motorcycle road racing in America has not met expectations for quite a while now. Our guys are no longer dominating GP racing as they did in decades past. MotoAmerica, our premier road racing league has made strides by reinstalling the 1000cc bikes as the premier class and bumping the 600’s down to B-team. Hiring my Internet-buddy Andrew Capone as rainmaker for the series is another great move towards professional sponsorship and revenue generation. I’ve never raced on pavement but I rank as an expert spectator due to the sheer number of road races I’ve attended. I’ve got a few ideas on how to make MotoAmerica better and I’m not shy about cranking them out. American road racers are never going to get back atop the pinnacle of GP racing until they test themselves against the world’s best. It’s expensive for a US rider to got to Europe so why not bring Europe to the USA? What if all the contract issues could be solved and MotoAmerica paid start money to a few of the GP guys? Pay Rossi to start a few races, Marquez or Dovizioso would be a huge draw. I’m guessing the increased gate alone would pay for Rossi. This harkens back to when European motocross stars were paid to compete over here. American racers gained first hand experience on where they needed to be in order to defeat the best. There is no physical barrier preventing our top AMA racers from competing on even terms with world-class GP racers. Show our greyhounds the European rabbit and they will move heaven and earth to stay on their tail.

American road racers are never going to get back atop the pinnacle of GP racing until they test themselves against the world’s best. It’s expensive for a US rider to got to Europe so why not bring Europe to the USA? What if all the contract issues could be solved and MotoAmerica paid start money to a few of the GP guys? Pay Rossi to start a few races, Marquez or Dovizioso would be a huge draw. I’m guessing the increased gate alone would pay for Rossi. This harkens back to when European motocross stars were paid to compete over here. American racers gained first hand experience on where they needed to be in order to defeat the best. There is no physical barrier preventing our top AMA racers from competing on even terms with world-class GP racers. Show our greyhounds the European rabbit and they will move heaven and earth to stay on their tail.