By Joe Berk

On our recent visit to Milwaukee, we visited the Miller brewery. It’s in the center of the city, right on West State Street, nestled in the town’s hills. Those hills will become significant in a moment when I tell you about the caves.

Our tour guide was a very energized guy. I can’t remember his name, but I can tell you he made the tour come alive for us. It was fun.

One of the first things our tour guide covered was the girl. She was present in several stained glass windows and a few other places.

Our guide, that interesting guy a few photos up, explained her history to us. The story goes like this: A.C. Paul, Miller’s advertising guy, got lost in the Wisconsin woods (as in good and lost, at night, in freezing temperatures). He had a vision of the Miller High Life girl you see above, perched on a crescent moon, pointing the way back to civilization. That vision (in various forms) has been in Miller’s advertising and branding pretty much ever since. Is it true? Hey, it’s a good story and it’s got something to do with beer, so who cares?

The Miller company goes back a long way, and in the old days, they used to store newly-made beer in the caves adjacent to the plant in the hills on West State Street. The advent of refrigeration made that unnecessary, but Miller still owns the caves. They’re part of the tour, and if you have an event (a wedding, a party, a Bar Mitzvah, whatever) they make a hell of a venue.

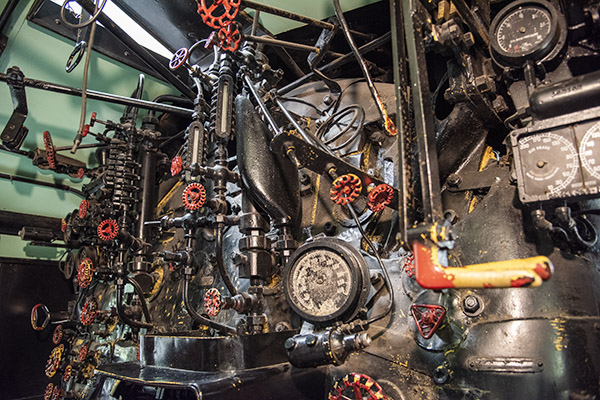

The photos you see here didn’t use any flash. I bumped the ISO up to 800. That, along with my 24-120’s vibration reduction capabilities and a bit of post processing in PhotoShop created the images you see here.

Miller has also has a cool party place (you can also rent this as a venue) in the main building. You can see that in the photo below.

Those glasses you see above were samples provided to us during the tour. The ones you see above were Miller’s Killian Red label. Folks, there were a lot of beer samples on this tour, starting with the very beginning of the tour in the Miller Visitor Center (it’s where I snapped that photo of the custom chopper at the top of this blog). The samples weren’t small, either. If you weren’t watching what you consumed, I imagine you could get a pretty good buzz on this tour. Me, I was watching what I drank, and I didn’t finish any of the samples. They sure were good, though. Miller beer is awesome.

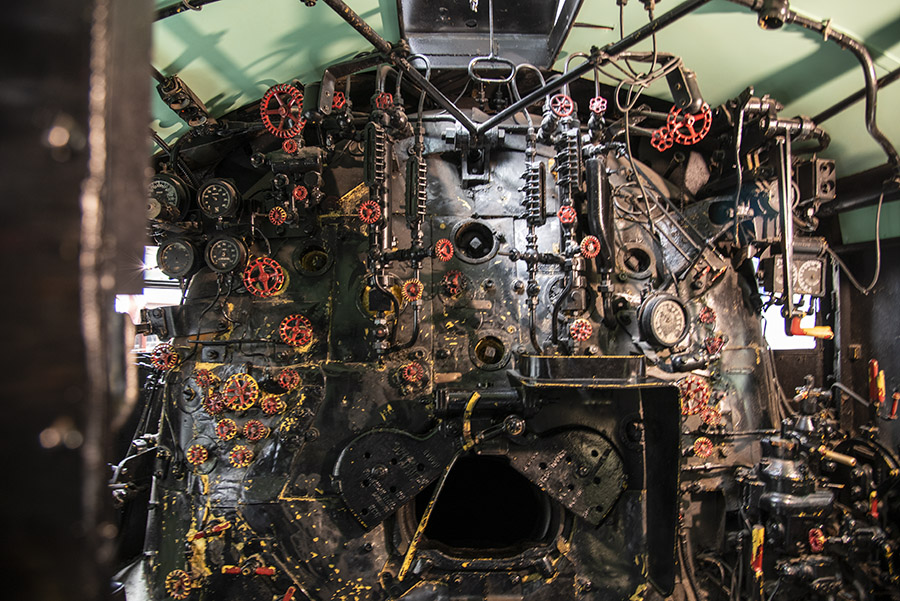

After the stop above, we entered the actual beer factory. Our guide explained that folks are usually amazed when they see this part of the operation. There were hardly any people working in the plant.

I wasn’t surprised at the lack of people; in fact, I would have been surprised if there were people there. Beer production is a process-based industry, and most process-based industries are automated. The days of the LaVerne and Shirley show are long gone in the beer business (that show featured two women who worked in a Milwaukee beer factory).

Back in the LaVerne and Shirley days, they could have been employed by any of several beer companies in Milwaukee. Automation and consolidation changed all that. Today, pretty much all the Milwaukee beer companies are part of the Miller empire. Miller has something like 11 breweries across the country. There’s one not too far from me here in southern California. The regions they cover are divided geographically. Our tour guide told us that the plant we were in covers the Midwest. It produces 10 million barrels of beer annually, and 40% of the beer manufactured in the Milwaukee plant goes to just one city (and that’s Chicago). Those Chicago boys like their beer, I guess.

Join our Facebook ExNotes page!

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

With the New Year approaching my plan was to begin traveling through South America for the entire year by motorcycle. In November that plan quickly changed (imagine that) when a fellow rider I had camped with four years ago in Death Valley National Park messaged me and stated that he and another rider were about to embark on a 1-month motorcycle journey through India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh in February on Royal Enfield Himalayans. I wasn’t too impressed as I figured it would be some BS tour with a guide and not really count as a motorcycle adventure. He replied stating that was not the case and it was just the two of them. It took me about 15 minutes to reply stating that I was in. He promptly let me know that he wasn’t inviting me and was just discussing the trip with me. At any rate I invited myself and they seemed okay with that. I mean, who wouldn’t be? I am an absolute joy to be around.

With the New Year approaching my plan was to begin traveling through South America for the entire year by motorcycle. In November that plan quickly changed (imagine that) when a fellow rider I had camped with four years ago in Death Valley National Park messaged me and stated that he and another rider were about to embark on a 1-month motorcycle journey through India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh in February on Royal Enfield Himalayans. I wasn’t too impressed as I figured it would be some BS tour with a guide and not really count as a motorcycle adventure. He replied stating that was not the case and it was just the two of them. It took me about 15 minutes to reply stating that I was in. He promptly let me know that he wasn’t inviting me and was just discussing the trip with me. At any rate I invited myself and they seemed okay with that. I mean, who wouldn’t be? I am an absolute joy to be around.