Or maybe the title of this one should be: Go West, Young Man! That’s what Ernie did, and that’s what I did, too.

My good buddy Ernie and I go back. Way back. As in kindergarten back. Hell, that was 62 years ago. That’s how long I’ve known Ernie. Elementary school, junior high school, high school, and beyond. Whoooeee!

Anyway, we’re coming up on our 50th year high school reunion back in the Garden State, and Ernie has been posting stories (along with a few other folks) about what’s gone on his life over the last five decades. Ernie’s stuff is good, and it sure hit home for me. I asked Ernie if I could run one of his stories here on the blog, and he agreed. You’ll like this…I know I sure did.

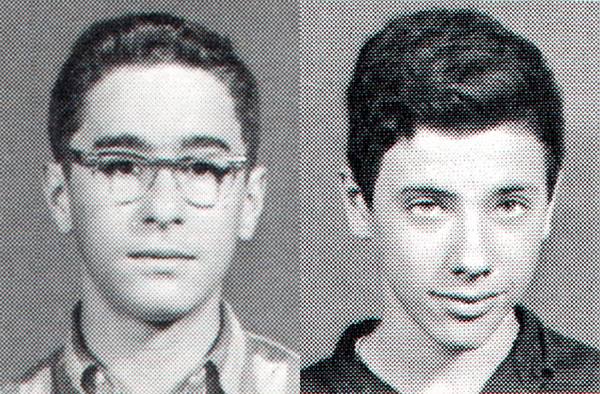

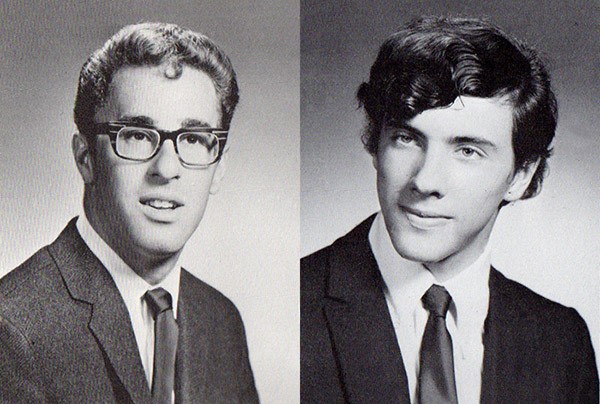

And those photos above? They are, as you probably guessed, from our school yearbooks. Yep, I still have them.

Ernie, over to you, my friend…

*************************************

Thanks, everybody, and especially you, Joe. I enjoy your tales on the trail. I have a few tales that you might enjoy, too.

In 1979 when our daughter Stephanie was born, we made one of our good friends Jim her Godfather. Jim was really cool. He and his brother were on a road trip with Jim’s wife Bonnie, and I was lucky enough to have met them and made friends with them, when I decided to get out of NJ and try my hand at the West.

I had been to Salt lake City about a half year before with two of my buddies. We had a few weeks where the 35-man shop was a bit slow due to the economy, so the three of us did a scouting expedition points West. We left in late October, and as luck would have it, we hit a bad snow storm in Pennsylvania.

After we made it through that, we pushed on across Ohio, Indiana and into Illinois. It was around midnight and as it has happened before to me since then, I-80 had construction and we made a wrong turn and were headed straight into the windy city. It was hell getting back on track and on 80 west again. We wasted a good hour. The highway around the area is a lot like the famed city. It blows, too.

Well, on we went. it was dark out when we were in western Nebraska and entering Wyoming. We stopped in a bar and my friend Paul, all he could talk about was Coors beer all the way from NJ, so we needed this break and to our delight guess what they had on tap. Well, it was pitcher time. All we heard was Paul’s mouth flapping happy about that ice-cold Coors.

When we got back on the road, and into Wyoming as luck would have it, a herd of mule deer were about to run out in front of us, but our headlights persuaded them not to. A while later we saw our first Western state’s snow. We stopped at a rest area and spent a good half hour throwing snowballs at one another. Finally, we rolled into Utah, and the sign said Port of Entry. The hell with the port, we wanted more Coors. Then we experienced our first big downhill run. Parley’s Canyon. 14 miles downhill at a 6% grade, winding through the Rockies.

We saw our first major “run-away truck lane.” If I was a semi, I would want to run away too. Then we saw a big opening and soon…ta dah…the Salt Lake Valley loomed in front of us. We intersected with I-15 and off to our left we spotted Dryer’s Harley Davidson. We decided that was going to be our first stop. Good thing too, because right next to it was a tavern. Well I can go on and on about this trip because we had some great experiences throughout Utah, which we circled, and some cool adventures on the way home with 25 cases of Coors beer. And we got stuck in a snowbank in Kansas, and a state trooper helped get us out. And, as luck again would have it, the exit we took led us to the hotel that they used in that movie Paper Moon. We stayed there. Yahoo!

So that scouting trip was the deciding factor that Chris and I were going to move to Salt Lake City. Months later my Dad and I took off in my Dodge van and drove across country to Salt Lake. I got the biggest kick out of my Dad, all the way across he was wide awake and thrilled at all the sights he saw. He stayed with me a few days till I found a good place to camp to look for an apartment. It was sad. It was the first and only time I saw my Dad tear up.

I camped out at the KOA on I-80. That’s where I met Jim, Bonnie, and Tom. They were on a bike road trip, and the cool thing about it was both Jim and Tom worked at the Harley-Davidson factory in Milwaukee. They both worked in engines and transmissions. Later Jim became a factory test rider. His job each night was to log in 250 miles on the test bikes (what a job, what a job!). They even sent him to Harley’s test track in Texas to race their bikes. We were at the big car show back in February and Harley had a big van there with all their new models. I entered a contest and got to talking to one of their staff. It turned out he knew Jim and Tom well. Jim still works there.

I went back to NJ to pick up my 1974 74 cubic inch dresser from my parents’ house. On the way out of NJ, I was pulled over by a state trooper who noticed my bike in the back of my van. I had shoulder length hair then and a beard and all, and I looked the part, I guess. Well ha, ha, ha. I whipped out my registration and bill of sale and foiled that trooper’s ideas.

I did lots and lots of riding while living in Utah with and without Chris. So, back to the main objective of the story, Joe. When our daughter was born we invited Jim and Bonnie to Stephanie’s christening. A few days later (this is now in Gresham, Oregon) I wanted to escort Jim and Bonnie out of town. It ended up I drove all the way to the California border with them, via the mountain pass at Eugene to Highway 101. Here is the part you may find fascinating, Joe. The Harley I had at the time was a stock 1965 Electra Glide. The problem was the front brake was out all the way down. The real issue was, the rear brake went out just when I started home from leaving Jim and Bonnie. I drove that bike up 101, through the hairy mountain pass and around that damn grooved circle they used to have in Eugene (you know how it makes your front tire wobble, Joe), then the 120 miles up I-5 in heavy traffic on the I-205 (which at the time was not completed) and on back roads to Gresham. It was challenging as hell, but a real thrill ride.

The other story is one of my best friends named John, who was a factory-sponsored, award-winning motorcycle racer for Harley-Davidson. He once rode a Harley from Seattle all the way to Portland on old highway 99 with tons of stop lights and through many small towns without a clutch, and never stopped or stalled the bike. He also hill climbed the widow maker between Salt Lake and Provo canyons, and get this, he took his Harley up to the top of Beacon Rock on Highway 14 (you know where it is, Joe), and he almost made it to the very top of Mt. Hood. The sun melted the snow and prevented him from making the last few yards.

Joe, this man was a legend. He built my 1947 Knucklehead from a basket case. The man knew every nut and bolt on just about anything that rolled sailed or flew. I was privileged to have known him.

******************************

Good stuff, Ernie, and thanks for allowing me to share it with our friends over here on the ExhaustNotes blog. We’re looking forward to seeing you next summer, Dude…we have a lot of catching up to do!

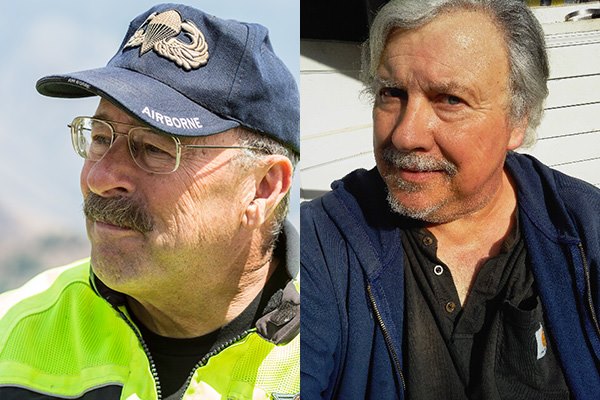

And for our great blog followers, you may be wondering how well the last 50 years have treated us.

Well, wonder no more, my friends…

Never miss an ExhaustNotes blog…subscribe here for free!

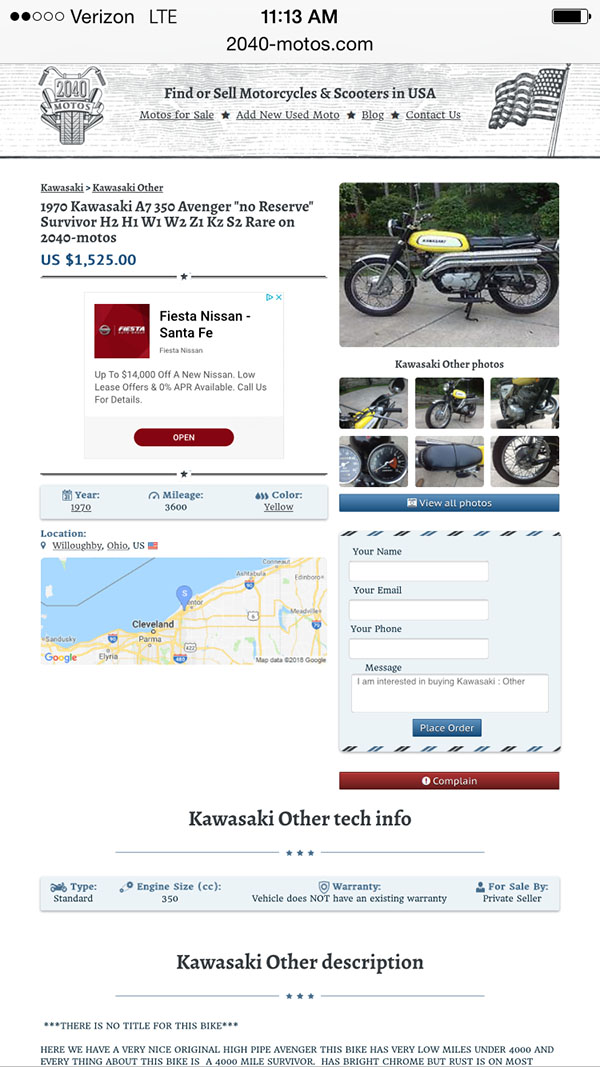

For me, the only knock on the A7 is that it may be too well made. I’m at the stage in my life where I don’t need a reliable motorcycle. New bikes are darn near perfect and perfection is boring. I search for the ever-elusive soul ride: Motorcycles that drip. The best motorcycles are the ones that leave you stranded; they turn any ride into a grand adventure. Besides, quirky flaws and secret handshakes appeal to my need to be special.

For me, the only knock on the A7 is that it may be too well made. I’m at the stage in my life where I don’t need a reliable motorcycle. New bikes are darn near perfect and perfection is boring. I search for the ever-elusive soul ride: Motorcycles that drip. The best motorcycles are the ones that leave you stranded; they turn any ride into a grand adventure. Besides, quirky flaws and secret handshakes appeal to my need to be special.