By Joe Berk

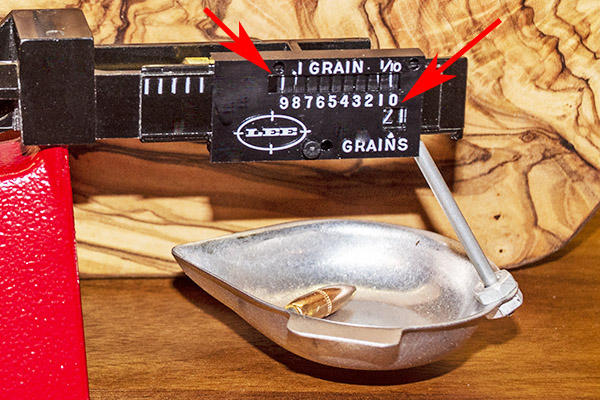

This is the next installment of our Lee Classic Turret Press Kit series, and this article focuses on Lee’s Safety Powder Scale. It’s the scale you see in the above photo and in the photos that follow. I haven’t assembled the turret press yet (that’s coming). Before I get to that, I’m doing this blog on the Lee scale, and then others on the Lee reloading manual and the Lee bench plate. These will be followed by blogs on the Lee turret press, the powder dispenser, the priming tool, and the 9mm dies I’ll use with this equipment.

Packaging

The box you see below was inside the Classic Turret Press Kit, and the Turret Press Kit’s box was inside a bigger box. It’s a box in a box (you know, Russian doll packaging, like I mentioned in the first blog on the Turret Press Kit). The Lee packaging is good. Everything arrived undamaged.

Lee Safety Scale Components

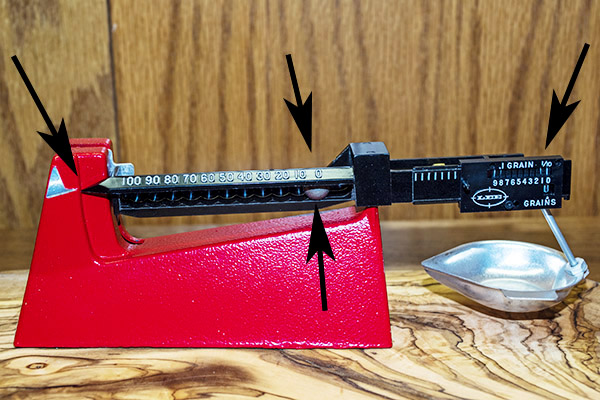

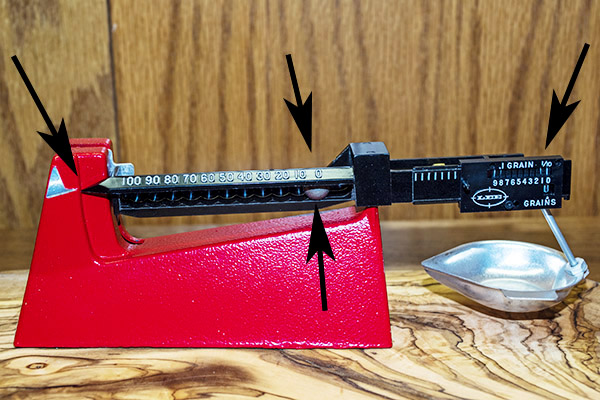

As mentioned in the photo above, there are three components in the Lee Safety Scale. These are the scale base (that’s the cast red frame in the photo below), the beam (I call it a balance beam; it’s the black subassembly in the photo below), and the pan (that’s where the material to be weighed is placed). The pan has an attached hook on it (it’s the bar extending up in the photo below) that hooks onto the right end of the beam.

The red base has a machined groove on the piece that extends up on the right side. The beam is placed over this, and it balances on a knife edge in this groove. There are magnets in the base to dampen the beam’s movement as it balances. The photo below shows the scale with everything in place.

The magnetic beam dampers in the scale base work. When weighing powder charges with the Lee scale, the beam balanced in just a couple of oscillations.

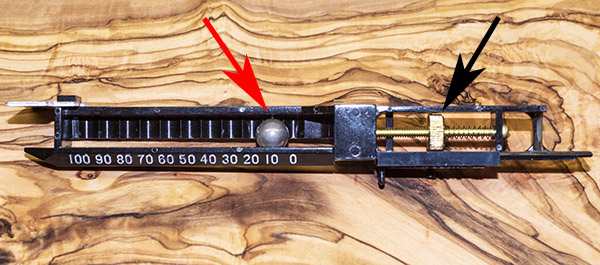

The Lee balance beam is a molded phenolic subassembly with two poises. “Poise” an engineering term for the movable weights that balance the beam. It’s a term Lee uses in their documentation.

When I was Director of Engineering at Aerojet (we designed and manufactured munitions…big stuff, 2000-pound bombs, anti-armor munitions, and other things I can’t tell you about), we used plastic on as many parts as possible (rather than metal) because plastic was less expensive, it does not not corrode, it can be molded to exact dimensions, and moving parts are less likely to jam. Lee makes some of these same points in their literature. My point here is this: Don’t dismiss the Lee balance beam because it is a phenolic part. From an engineering perspective, it is the right choice. As Richard Lee (Lee Precision Products founder) stated in his excellent reloading manual, Modern Reloading:

Lee Safety Scale has a phenolic beam. Like a glass thermometer, if it is not broken it is still accurate.

Incidentally, the next blog in this series will be on Lee’s Modern Reloading book. I’m reading it now and it’s good.

The Lee pan is a one-piece subassembly that consists of an arm (the pan hangs from it on the right side of the beam) and the pan. The pan can be a bit difficult to get under a powder dispenser because the arm gets in the way. That’s not a big deal, and when I was weighing .357 Magnum charges with the Lee scale (so I could adjust my powder dispenser to drop the correct charge), it didn’t affect my ability to catch and weigh the powder.

Measurement Range

The Lee scale can measure up to 110 grains. That’s good news and bad news. Most of us use powder scales for measuring powder, and if that’s your purpose, the Lee scale is the right tool. The 110-grain measurement range gives superior sensitivity for detecting slight weight differences. Other balance beam reloading scales can weigh up to 510 grains, but they do so with the same range of motion as the Lee scale, and that means they don’t provide the same sensitivity.

Sometimes we wish to weigh bullets (competitive bench rest shooters and cast bullet shooters might want to sort bullets by weight). On the Lee scale, you can only weigh bullets that are 110 grains or less. I’m what I would call a serious reloader, and in the last 50 years, I might have weighed bullets maybe a half dozen times. I’m happy to lose the ability to weigh bullets in exhange for the increased sensitivity I’ll get when weighing powder charges with the Lee scale. Your mileage may vary.

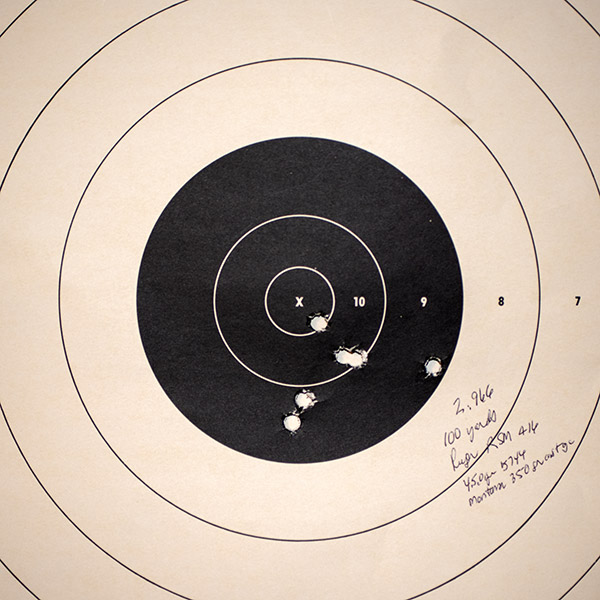

The bottom line is this: For weighing powder, the Lee scale does a superior job within its measurement range, and that range is adequate for any thing I shoot (that includes .22 Hornet, .416 Rigby, .458 Win Mag, and many handgun and rifle cartridges in between). For weighing bullets over 110 grains, you would be better served with scales offering a greater range than the Lee scale, but you give up accuracy with those scales. Do you really need the increased weight range? Most of us do not.

Zeroing the Scale

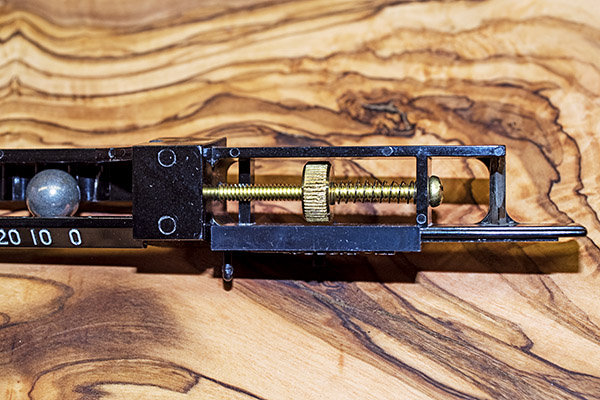

Like all scales, the Lee Safety Scale requires zeroing before use. Lee incorporates a threaded brass weight (in the form of a wheel) in the balance beam to move the beam up or down on its pivot in the base.

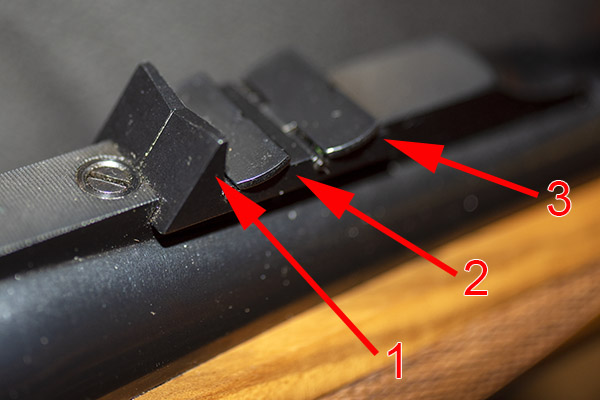

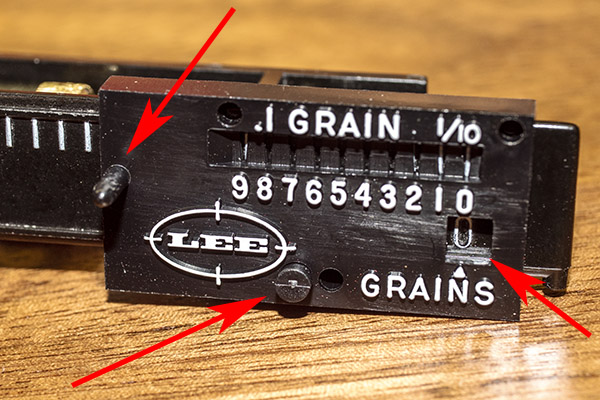

The idea is you set the both poises to zero (see below). To set the 10-grain poise to zero, you roll it all the way to the right, and it comes to rest on the zero marker. The balance beam has ridges that will position the 10-grain poise ball bearing in 10-grain increments, starting at 0 and going up to 100 grains. To set the 1-grain poise to zero, you slide it all the way to the right, and lock the poise in the zero position with a little locking button on the bottom of the poise.

When the two poises are set to zero (as explained above), the brass wheel in the balance beam can be rotated to zero the scale. As the brass wheel is rotated, it moves to either the left or right along its threaded shaft depending on which way the wheel is turned. The idea is to turn the wheel until the balance beam is aligned with the index mark on the scale base as shown below.

Using the Lee Safety Scale

Using the scale after it has been zeroed when setting up a powder dispenser involves setting the desired powder charge with the 10-grain and 1-grain poises, and then adjusting the dispenser to provide an amount of powder that matches the scale adjustment. It’s fairly straightforward, although using the 1-grain poise with its Vernier tenth-grain readings may be new to some people.

Or, you may have an item you wish to weigh. Reading the scale is the same in either case. It involves setting the 10-grain poise in the appropriate notch, and then moving the 1-grain poise to the appropriate place.

After I had zeroed the scale, I wanted to check its accuracy. I weighed a .224-inch diameter, 62-grain Hornady jacketed boattail bullet to do this. I put the bullet in the pan, moved the 10-grain poise to the 60-grain position, and then moved the 1-grain poise laterally along the balance beam until the beam was aligned with the base index mark.

Using the 1-grain poise is a bit tricky. In the photo below you can see that the poise shows 2 grains in the lower window. The Vernier windows on top of the 1-grain poise show that the 0 and .9 grain windows are aligned with visible lines, and a window is just a bit aligned with the .1 grain windows above and below the 0 and 9 windows. Like I said, interpreting the Vernier approach is a bit complicated, but the Lee instructions contain several photos explaining how to do it. What you see below for this measurement is interpreted to mean that the weight in tenths of a grain around the 2 grains in the lower window is somewhere between 1.9, 2.0, and 2.1 grains, and I interpolated that as 0.0 grains away from 2.0 grains. Stated differently, the measured bullet weight is 62.0 grains, which is exactly what it is supposed to be.

As a check, I also measured the bullet’s weight with the RCBS scale I’ve been using for the last 50 years, and it returned the same weight: 62.0 grains.

Cost

Lee did their usual outstanding job here: The Lee Safety Scale price is significantly lower than the competition. The Lee scale lists for $46.98 on the Lee website (interestingly, they also list factory second scales for $31.32). You can also purchase the Lee scale from Amazon and other retail outlets, and Lee tells you on their website that their retailers typically have lower prices than Lee advertises.

The nearest competitor to the Lee scale is the RCBS M500 mechanical scale, and that lists for $125.99 on the RCBS website. From a cost perspective, Lee is the clear winner here.

Documentation

The Lee scale includes a single-sheet, two-page instruction sheet. It’s good, and it provides all the information you need to set up and use the Lee scale. As mentioned above, the Lee instructions include information on using the Vernier feature on the 1-grain poise.

The Bottom Line

The Lee Safety Scale is accurate, inexpensive (less than half the cost of competitor products), and well built. Reading the Vernier scale to get tenths of a grain takes a little bit of study and practice, but once you get it, you’ll find it quick and easy to use. This is a good scale, it will serve any reloader well, and it should last a lifetime (and then some).

Help us out! Please click on the popup ads! And check out what else is available from Lee Precision.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

Read our blogs on unveiling the Lee Classic Turret Kit and the Lee Deluxe 4-die sets:

On our return ride it was time to make food choices again. Choosing to stop at the first crowded place made sense. We soon discovered an establishment and radioed to each other that this looked acceptable. Instantly, all eyes were upon us as we sat down in a three-walled, white-paint-chipped open room. One thing we found in Vietnam wat that when you order food, you don’t always get what you asked for. Often you get what they have, even though they will nod their head to your request while saying “ya ya ya.” In this restaurant we kept it simple and ordered pho.

On our return ride it was time to make food choices again. Choosing to stop at the first crowded place made sense. We soon discovered an establishment and radioed to each other that this looked acceptable. Instantly, all eyes were upon us as we sat down in a three-walled, white-paint-chipped open room. One thing we found in Vietnam wat that when you order food, you don’t always get what you asked for. Often you get what they have, even though they will nod their head to your request while saying “ya ya ya.” In this restaurant we kept it simple and ordered pho.