By Joe Berk

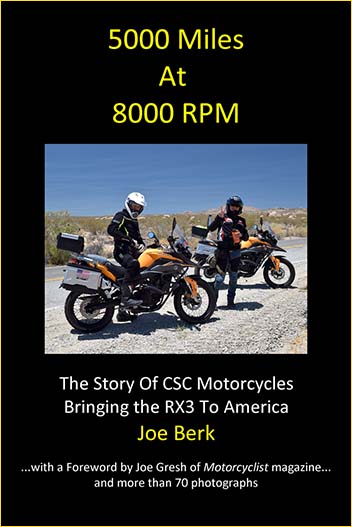

As mentioned in our introductory Idaho blog, I had briefly visited the Craters of the Moon National Monument on the 5,000-mile Western America Adventure Ride with the Chinese and other folks who owned RX3 motorcycles. Good buddy Baja John did all the navigating and planning on that ride; I just rode at the front of the pack and took all the credit.

We planned those early CSC trips as if it was just Baja John and me riding, and I figured on way too many miles each day. John and I can do 600-mile days easily. When we planned the larger Western America Adventure Ride, even 400-mile days were a huge challenge. A good rule of thumb on such larger group rides is to stick to a maximum of 200 to 250 miles each day. I didn’t know that then.

Anyway, on that first Craters of the Moon stop, we were on a big mileage day and we didn’t have too much time to spare. We pulled into the Craters entrance, grabbed a few photos, and continued our trek to Twin Falls. I recently wanted to do a Destinations piece on Craters for Motorcycle Classics magazine, and when I looked through my files, I found I only had a couple of Craters photos. That dearth of useable photos became part of the reason Susie and I visited Craters again.

The ride from Boise (where Susie and I started that morning) to Craters takes you east on I-84 and then east on US Highway 20. As an aside, Highway 20 runs across the entire United States, from Newport, Oregon to Boston, Massachusetts. Part of Highway 20 in Idaho was designated as the Medal of Honor Highway by Governor Brad Little in 2019, and Susie and I took it to Craters.

After Highway 20, it’s a left turn onto Highway 26 to get to Craters of the Moon. It’s more scenic riding, including the towns of Carey and Picabo. Carey is where we had a comical encounter on the Western America Adventure Tour when riding with our Chinese compañeros across Idaho. On that day 10 years ago, it happened to be Pioneer Day. We didn’t know that, nor did we know that there was a parade in Carey. I was in my usual spot (in front of the pack), Gresh was riding alongside me, and our group of a dozen RX3 riders were right behind us. As we approached Carey, local residents lined the streets. Many were holding American flags. They waved and cheered us as we rode into town. We had no idea what was going on. Gresh flipped his faceshield up and said, “Wow, a lot of people are following the blog” (I had been blogging our trip across the western US every day). We didn’t know it at the time, but we were only a few minutes ahead of the parade Carey was expecting, and those good Idahoans thought we were the advance guard. It was fun and it made for a great story (which I have told about a thousand times by now).

The good folks in Carey were not waiting for Susie and me on this trip, but we had a good time anyway. When we rolled into Picabo a little further down the road, we had an even better time when we topped off the Jeep and had lunch (which was excellent). I told you a bit about that (and the Ernest Hemingway connection) yesterday.

The National Park Service describes the landscape in and around Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve as “weird and scenic” and that’s an apt description. The landscape is almost lunar-like. Its alien features consist of mostly dark brown solidified lava surrounded and sometimes punctuated by patches of green vegetation. It makes for a dramatic landscape and awesome photo ops.

You can ride a designated, one-way, circular tarmac road through the Preserve, with paved offshoots for specific sights. One of the first stops is a pahoehoe lava field. The name is a particular type of lava, and it comes from the lava volcanoes and their flows in Hawaii. Pahoehoe lava is characterized by a rough and darkened surface. What made it even more interesting is the walkway above the lava. You can walk a loop of about a quarter of a mile and see what the hardened lava looks like. The walkway is a good thing; I don’t think it would be possible to navigate this terrain on foot.

Another lava structure is called cinder cone. Sometimes these structures break apart and leave monolithic forms like those in the photograph above. One of the more dramatic areas in Craters of the Moon is the Inferno Cone. There’s a place to park near the base and you can climb to the peak.

There are several lava tubes (caves formed by lava flow) in Craters of the Moon, and if you wish, you can hike into them. We didn’t do that. There are also longer hikes throughout the Preserve if you want to explore more.

There’s much to see and do at Craters of the Moon. How long you stay and how much you see is up to you. We were there for about three hours and we had a great visit.

The next stop on our Idaho expedition would be Twin Falls. That’s coming up, so stay tuned.

If you would like to read about the Western America Adventure Ride and how CSC rewrote the motorcycle adventure touring book, the story is here:

Never miss an ExNotes blog: