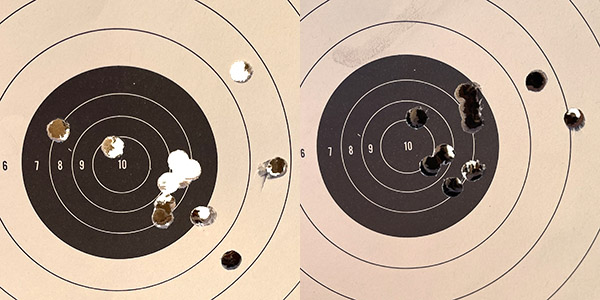

I should have won. It was politics, I tell ya…that’s the only reason the Axis prevailed. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

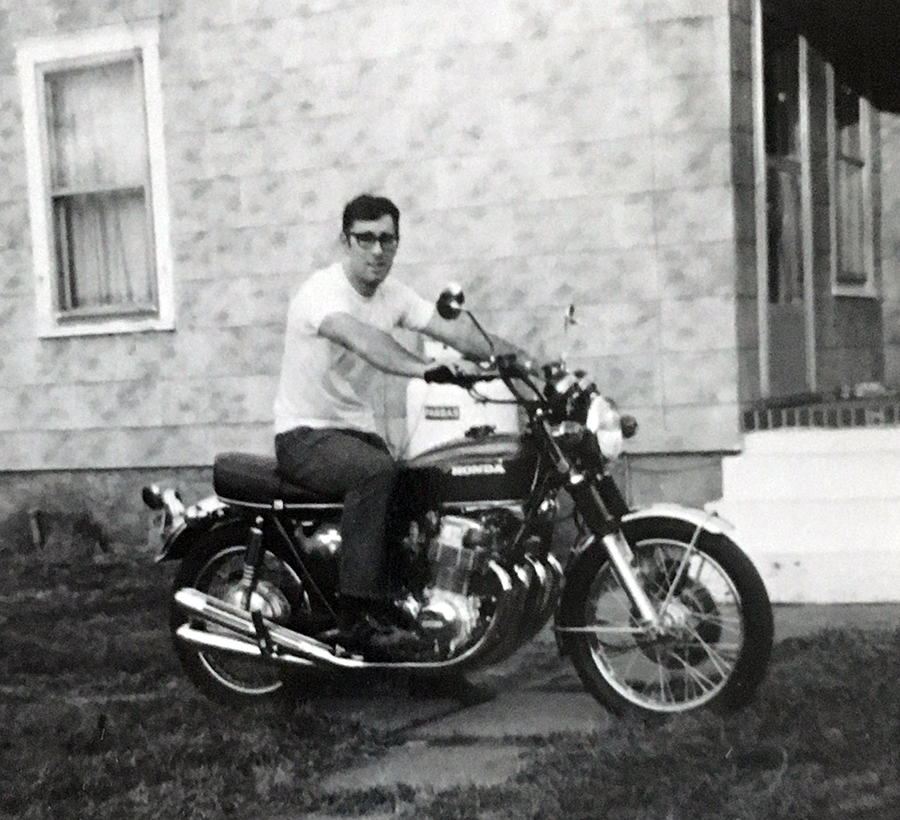

That photo above? Like I said, I should have won. That’s my photo. I watched the two judges, stooges of the Axis powers, deliberate for several minutes, even delaying announcement of the winner while they looked for a plausible reason to deny what was rightfully mine.

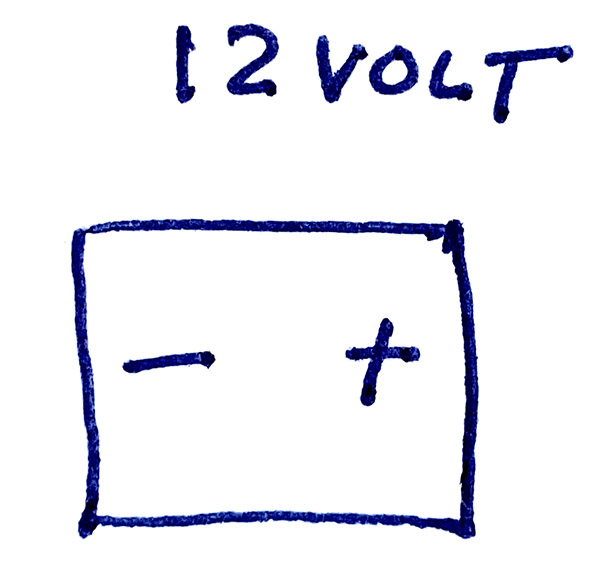

Okay, back to the beginning. Me and the boys used to hang out at Bob Brown’s BMW dealership on Saturday mornings, and back in the day, Bob and crew were always coming up with great ideas…you know, things to do. They outdid themselves on the Shoot and Scoot deal. You see, one of Bob’s BMW customers owned a camera store down in Chino Hills. Between Bob and the camera guy, they had this idea: Combine a day-ride to the Chino Planes of Fame Museum and a photo contest. It worked for me. I ride (my ride was a Triumph Tiger in those days) and Lord knows I’m a photography phreak. I was in.

The day started with photo ops and donuts at Bob’s dealership, with a very attractive young model. Attractive, yes. Creative or unusual? Hardly. But I grabbed the obligatory fashion shot…

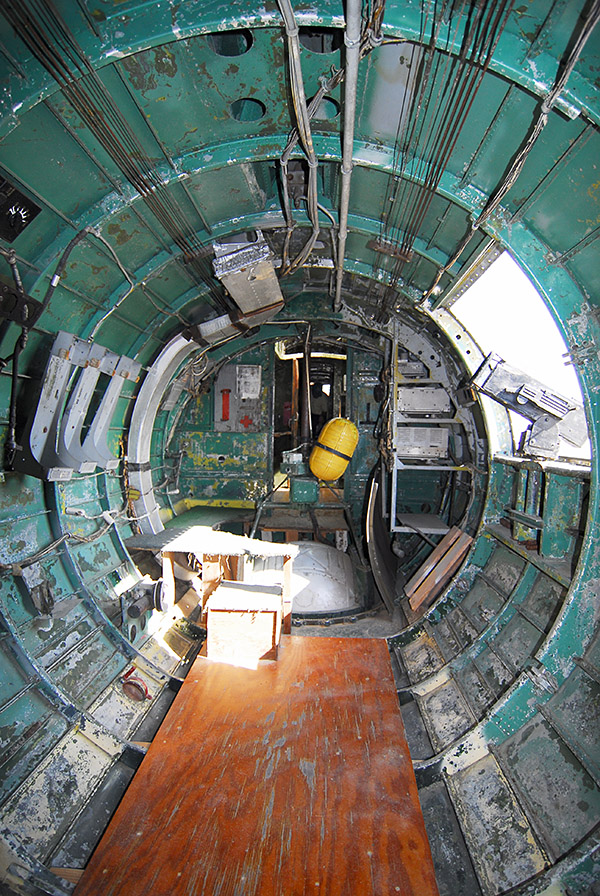

From there, it was a quick ride to the Chino Airport’s Planes of Fame Museum. I’ve always loved that place. The idea was to grab an interesting photo or twenty in a place jam packed full of interesting photo ops. Trust me on this, boys and girls…if you’ve never been to the Planes of Fame Museum, you need to go.

From there, it was a quick ride to the Chino Airport’s Planes of Fame Museum. I’ve always loved that place. The idea was to grab an interesting photo or twenty in a place jam packed full of interesting photo ops. Trust me on this, boys and girls…if you’ve never been to the Planes of Fame Museum, you need to go.

Anyway, these are a few of my favorite shots from that day…I was working the Nikon for all it was worth and I was having a good time. I could win this, I thought.

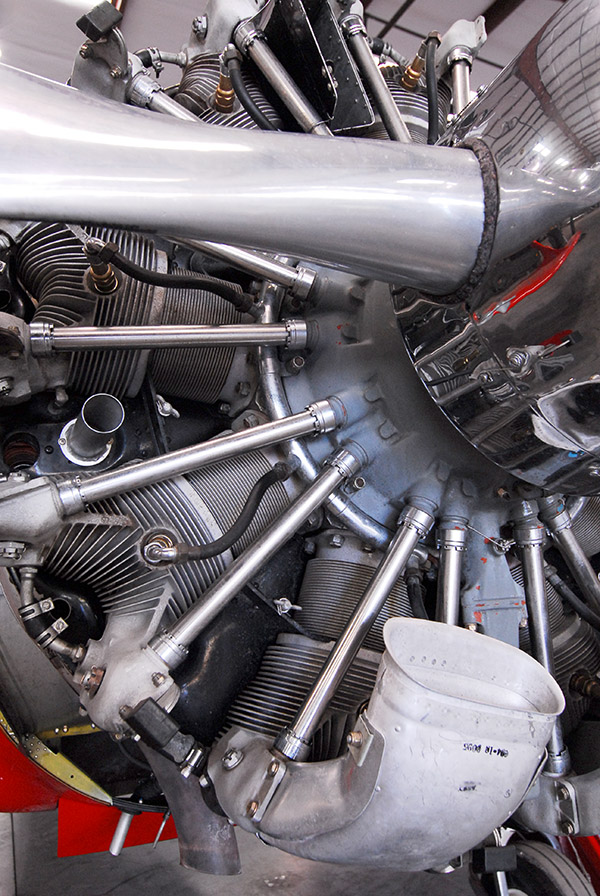

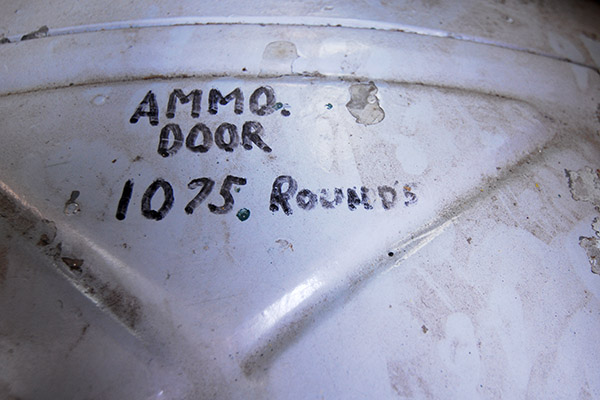

My last few photos of the day were of my reflection in that big radial engine you see above, and then it hit me. Like a politician who knows never to let a good crisis go to waste, when I have a camera that’s how I feel about reflective surfaces. I was getting some good shots of myself in the polished prop hub, and then it hit me.

“Hey Marty,” I said. Marty is my riding buddy. You’ve seen him here in the ExNotes blog in many places. Mexico. Canada. All over the US. “Get in the picture right here.”

And he did. That’s when I grabbed the photo you see at the top of this blog, and as I saw the image through the viewfinder, I knew I had a winner. It captured what the day had been about. Great photography. Air cooling and internal combustion. Riding. Friendship.

So we rode from the Planes of Fame Museum over to the photo shop and uploaded all our shots. We returned that evening when the winners would be announced. I wasn’t interested in placing. I wanted to win. And I knew I would. Or at least I knew I should. The funny thing was, the two judges were the camera store owner and the local Canon sales rep. I could see they were having a tough time. They were down to two photos, mine was one of them, and they were struggling with the decision. I think my photo was the clear winner. But alas, I shot it with a Nikon. This was a Canon contest being at least partly sponsored by a BMW dealer (and I rode a Triumph). The Germans and the Japanese. The Axis powers. Still trying to make up for World War II. Not that it bothers me. Much. But I should have won.

Never miss any of our stories…sign up here for free!