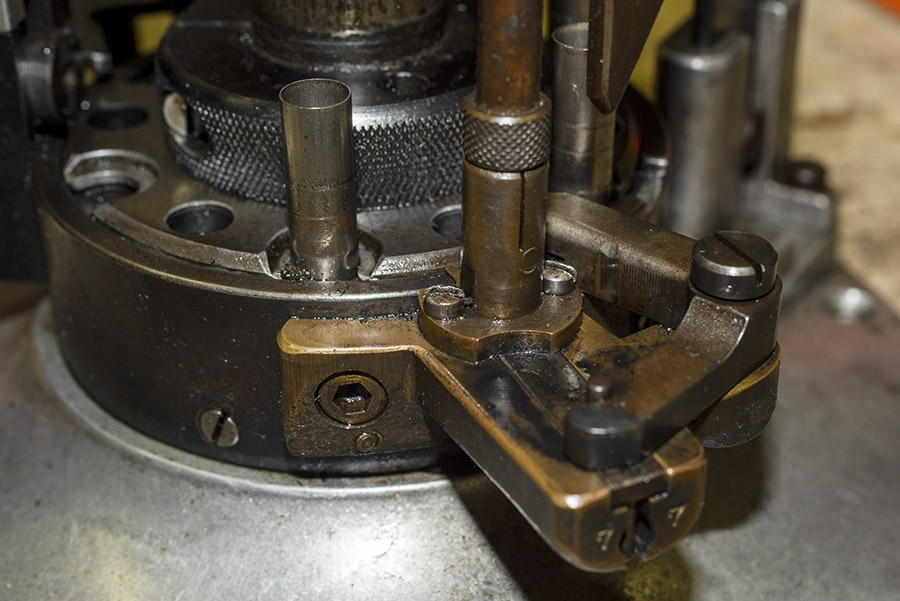

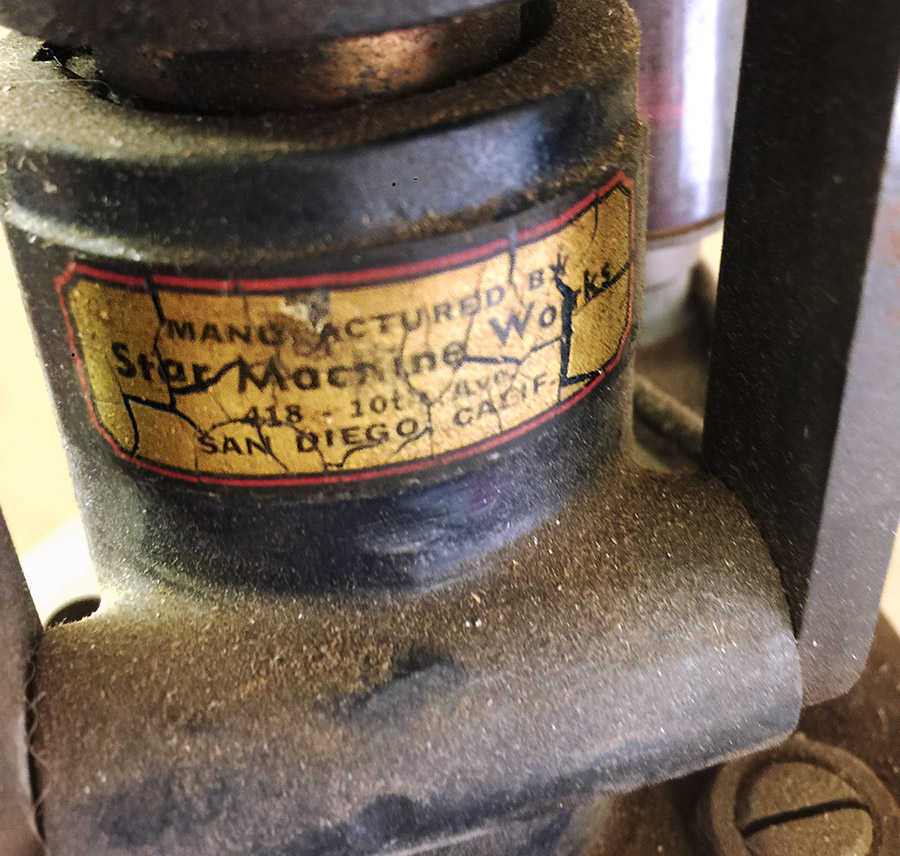

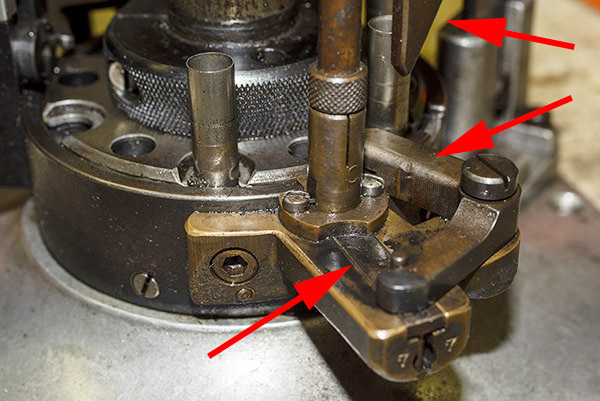

The next steps in bringing the Star progressive reloader back to life focused on the primer feed mechanism. That subsystem consists of the primer follower rod (the upper red arrow in the photo below), the primer magazine (the middle arrow in the photo below), the primer pickup and feed mechanism (the lower red arrow in the photo below), and the primer seating device (which is under the base of the reloader, as you’ll see further along in this blog).

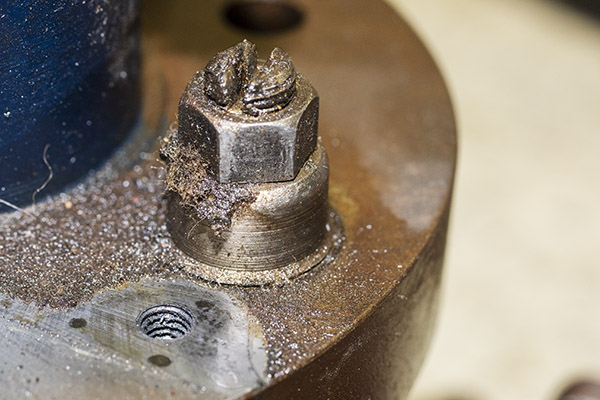

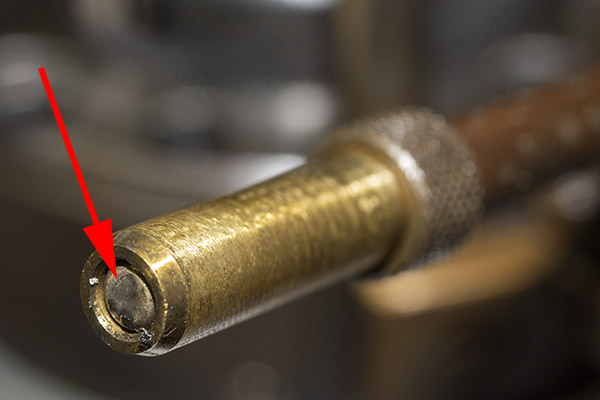

In looking at the primer feed mechanism, the primer magazine , and the primer follower rod, I could see they were mighty funky and thoroughly oxidized. I wondered if they were all made of brass. The tip of the primer follower rod obviously was (see the photo below), and probably the feed mechanism base was, but the magazine tube and other parts were so corroded I couldn’t tell.

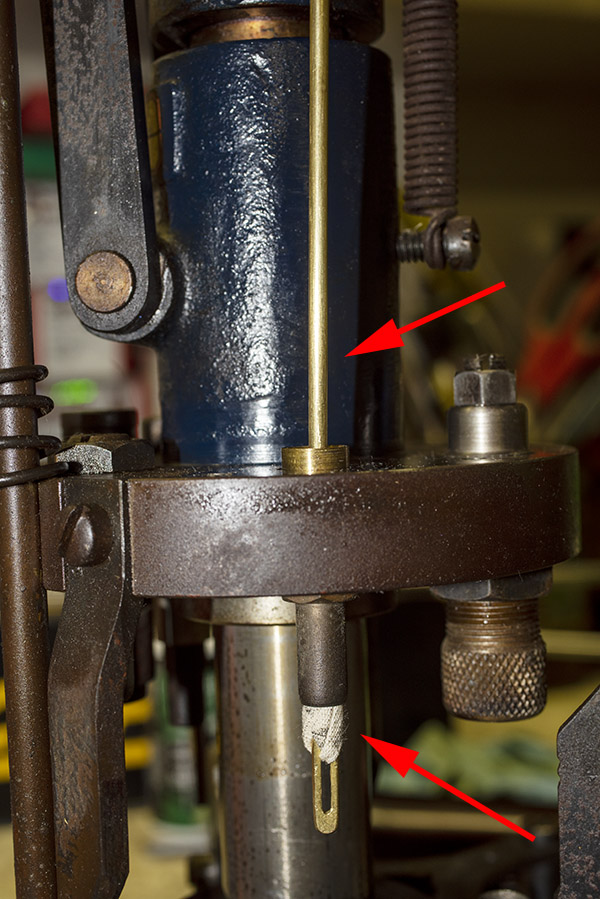

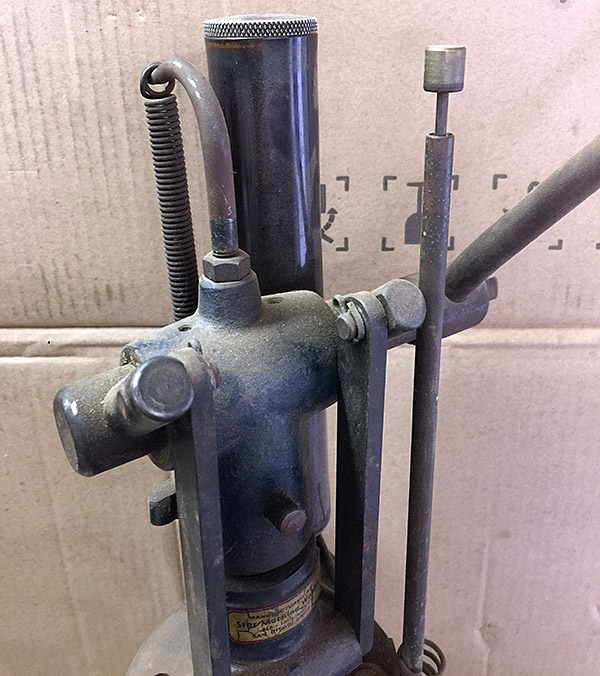

Then I realized I had another question. See the spring in the photo below? That one through me for a loop. I couldn’t see that it served any function, and all the online references I found for Star reloaders did not show it. So I sent an email to my good buddy Bruce over at Star Machine Works (the outfit that restores and sells parts for Star equipment).

Bruce responded quickly. Here’s what he told me:

Hi Joe,

The spring is a hitch hiker on your machine. Nothing to do with a Star.

Bruce

A hitch hiker. That got a laugh.

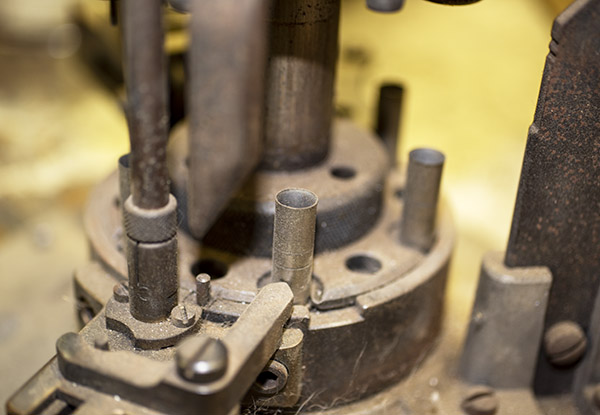

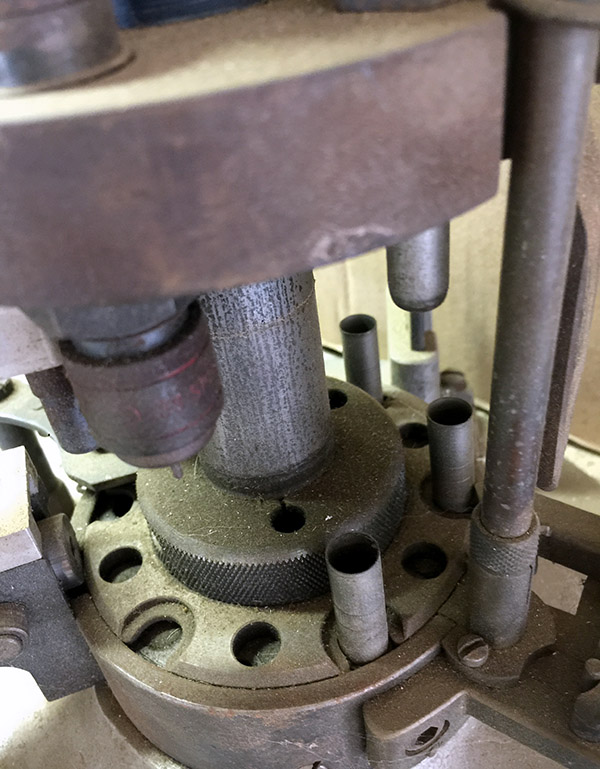

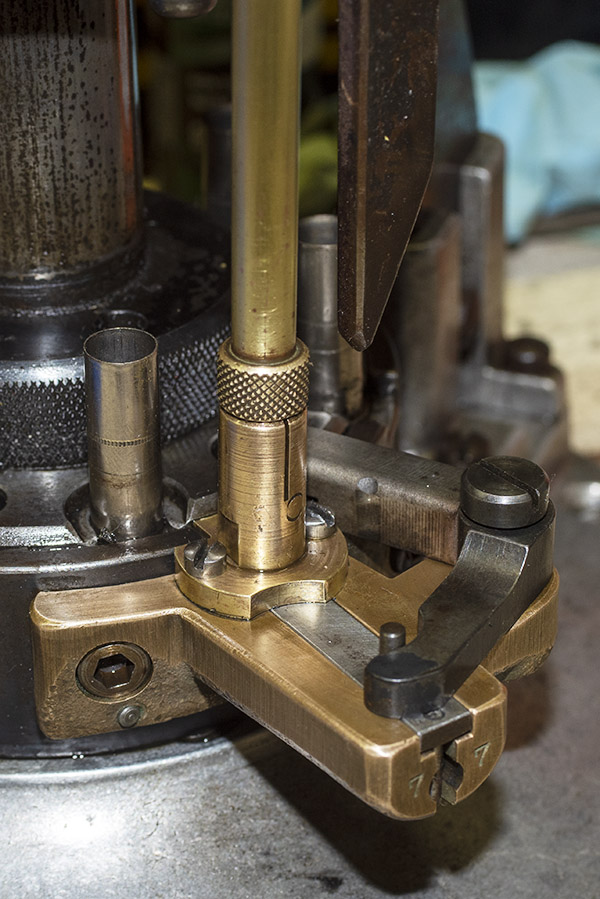

The primer pickup and feed mechanism (shown below) is what takes primers from the primer magazine and pushes them below the empty case. That L-shaped lever on the right? It’s the primer slide angle lever (shown by the lower arrow). It’s actuated when the primer feed cam (shown by the middle arrow) descends as the tool head is lowered on each stroke. The lever in turn actuates the primer slide in the feed mechanism (shown by the lower arrow), and that’s what picks up a primer from the magazine and positions it underneath the empty case.

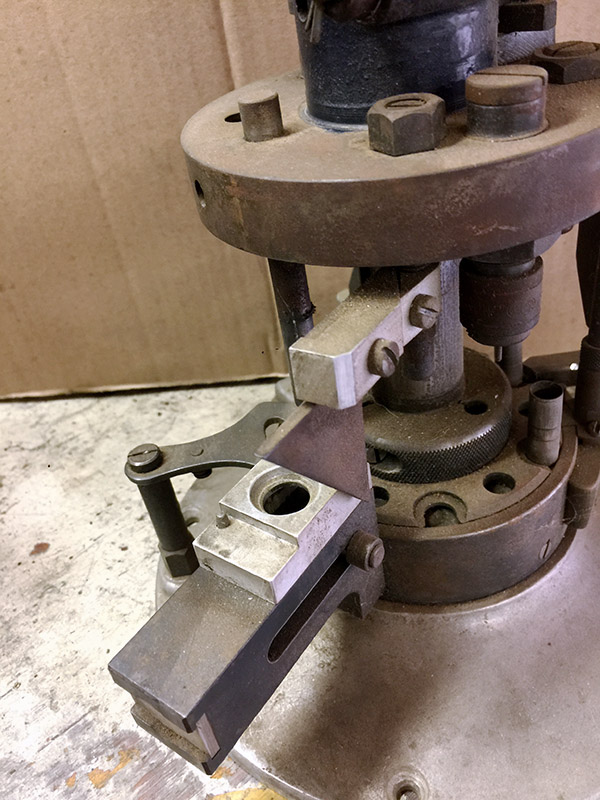

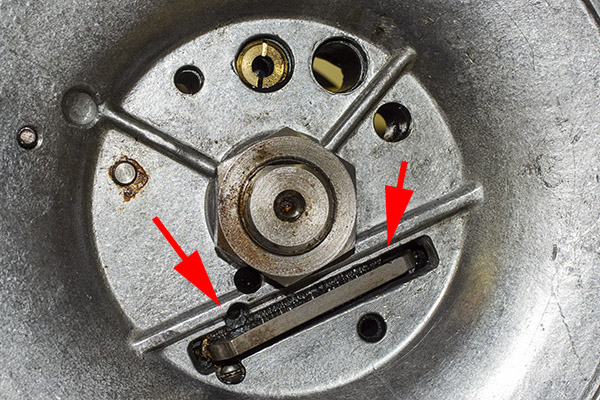

With the primer now in position beneath a .38 Special case, it needs a way to be inserted into the case. The Star has a clever way of doing this that takes advantage of the fact that there’s a shaft in the tool head that descends with the tool head when the main lever is pulled. When the main lever is actuated and the tool head descends, the shaft fits through a hole in the shell plate and extends into the base of the reloader. The tip of the shaft pushes one end of a pivoted lever down, and that then pushes the other end of the lever up. That end actuates a plunger that seats the primer into the empty case. Here’s what the lever looks like underneath the reloader.

Like I said, it’s all quite clever. The guy that designed the Star was a mechanical genius.

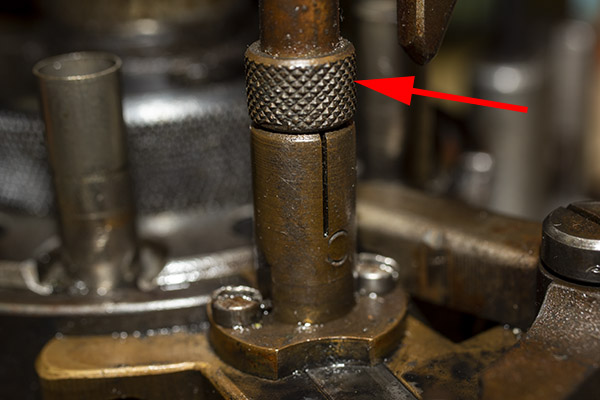

Here’s a photo of the primer follower rod. It sits on top of a stack of primers in the primer magazine. Its weight pushes the primers down each time one is transferred from the primer magazine by the primer slide.

The knurled knob below allows you to grasp the primer magazine to remove the tube from the primer feed mechanism. It doesn’t unscrew; it’s just a tight slip fit into the feed mechanism.

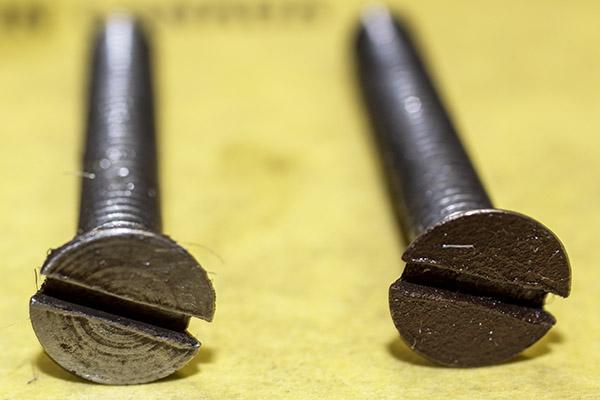

When I removed the primer magazine, I could see that the tube was made of brass. There were still a couple of primers in it. I doubt they would fire; they were probably soaked in oil.

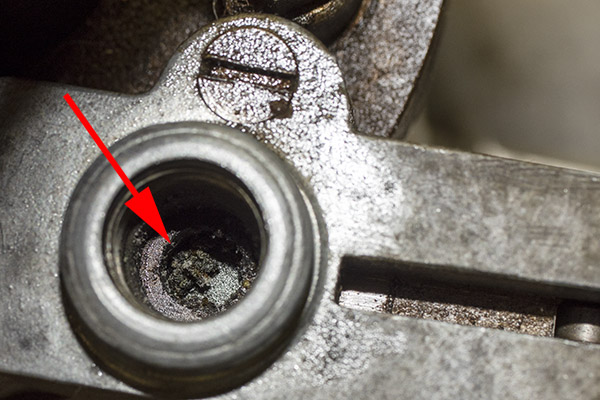

When I removed the primer slide angle lever screw, the primer slide was pushed out by its spring. As I was disassembling the primer feed mechanism, I found that the primer slide still held a primer. These parts were pretty funky. In a working reloader, you don’t want any oil in this area. It will contaminate the primers and make them inert (we only want “ert” primers when reloading ammo).

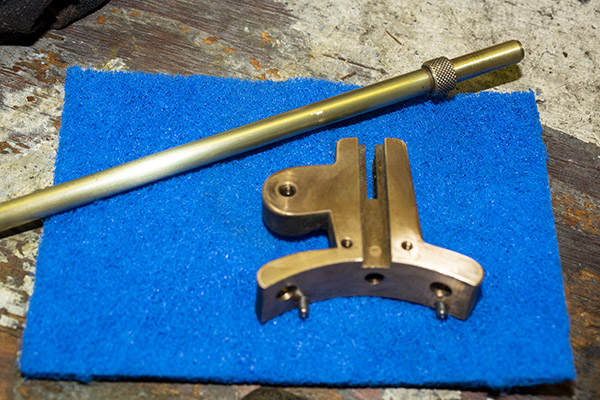

Check out the funk on the primer slide angle lever. This machine had been rode hard and put away wet, I think. My spraying it down with WD 40 to clean didn’t help in that regard. But it sure helped to clean up the Star.

I then unscrewed the two screws holding the primer magazine socket to the primer feed mechanism housing. Here are the parts in all their glorious funkiness.

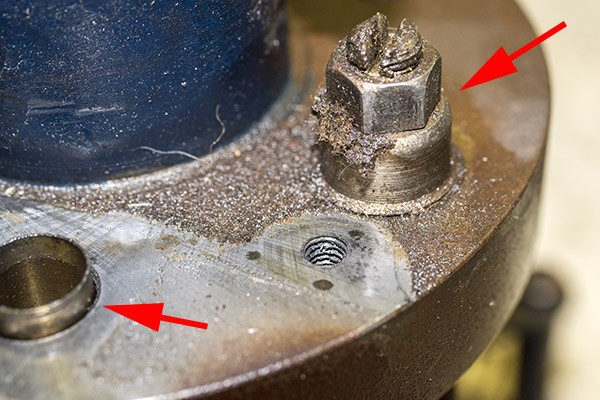

The primer feed mechanism base is attached to the steel floor base with two large Allen bolts.

I removed the Allen bolts and then took the primer feed mechanism base off the machine. It had two pins to locate it on the Star reloader’s base.

Here’s another exploded view photo of the primer feed mechanism and its components.

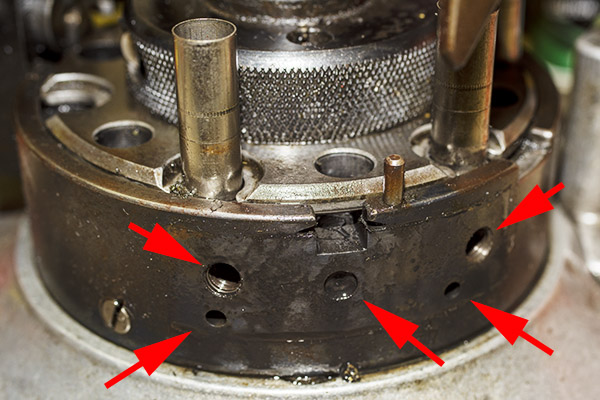

The photo below shows the reloader’s steel base and where the primer feed mechanism attaches. The upper two arrows point to the Allen bolt attach points. The lower two arrows point to the locating holes (this is where the two pins mentioned above fit). The arrow in the middle points to the hole for the primer slide spring. The rectangular slot is where the primer slide enters the reloader base to position a new primer beneath a .38 Special case.

The steel base is a blued steel part. It’s just like the bluing on a gun. This is a pretty cool feature. There’s a fair amount of corrosion and discoloration on my Star, but it’s part of the machine’s charm. I hit it with some OOOO steel wool and Kroil

, but I’m not going to reblue it. I like its patina.

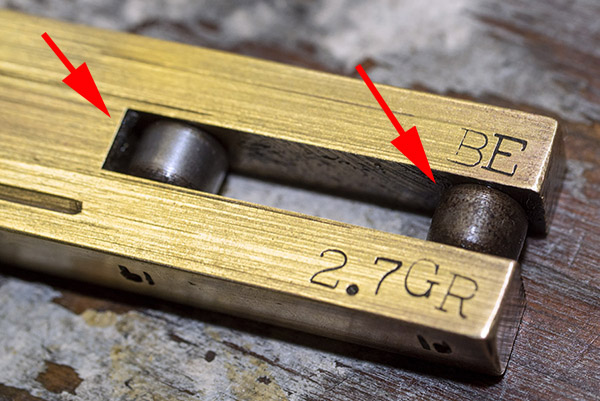

I next turned my attention to the primer magazine (the long tube I pointed out earlier). When I withdrew the primer magazine from its slot, I could see the lower end of the tube was brass, but I still wasn’t sure about the entire tube. I went to work on the tube with Scotchbrite and that did the trick. Hello, Beautiful!

I worked on all of the primer feed mechanism’s brass pieces with Scotchbrite. The brass finish came up nicely. This project is coming together fabulously well.

After cleaning and polishing everything, I reassembled it all. I could have polished everything to a mirror finish, but you know the drill: This is a resurrection, not a restoration. Like I said above, I like the patina look. This machine might be older than me, and I sure don’t look like new. We match, the Star and I do. Old. Funky. The ultimate in personalized patina. That’s us.

In the photo below, you can see the primer cam to the right of the brass magazine tube. It’s the part that actuates the primer angle lever. You’ll get to see it all in a short video in just a minute. People like videos, Gresh tells me. We aim to please.

It’s beautiful, isn’t it?

So how does it all work? Gloriously well, thank you. Take a look:

Next up? It’s going to be the case feed mechanism, and that will be the topic for our next Star blog.

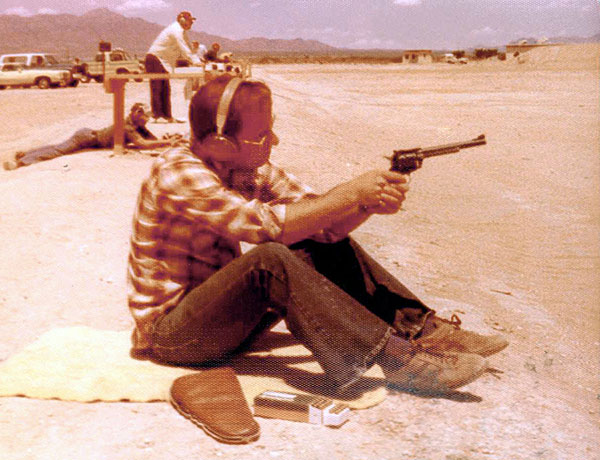

I’ll share with you that the blogging part of this Star resurrection business is lagging behind the actual resurrection. Yep, I actually have the Star running already, and it’s running well. You’ll see how I got there in future blogs, and those blogs will be right here in the not too distant future. But I don’t mind jumping ahead a tiny bit to tell you that I picked up my Model 60 Smith and Wesson yesterday morning and I fired the first few rounds I made on the Star through it. They worked just like they were supposed to, as did the Model 60. That’s a story for a future blog.

Stay tuned, my friends!

Hey, here are the Star resurrection blogs so far, along with our other Resurrection projects!