I started playing with guns when I was a youngster and the disease progressed as I aged. I almost said “matured” instead of “aged,” but that would be stretching things, especially when it comes to shelling out good money for fancy guns. When I see a rifle I want, I haven’t matured at all. I sure have aged, though.

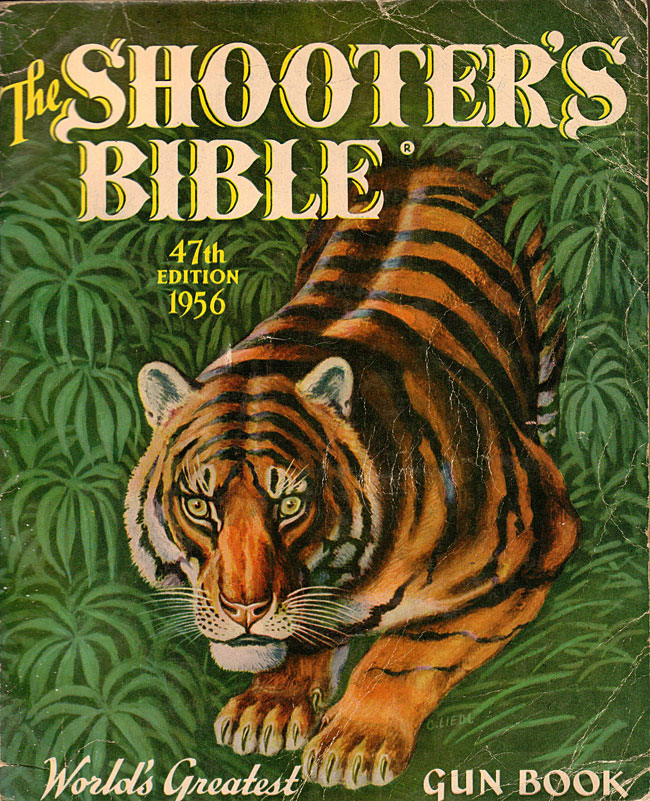

So anyway, when I was a young guy, I read everything I could about all kinds of guns, and I especially enjoyed reading about big game rifles. Really big game, as in Peter Hathaway Capstick chasing cape buffalo, Jim Corbett chasing man-eating tigers in India, and Colonel John Henry Patterson chasing the man-eating lions of Tsavo. It was all books and magazines back in those days. Al Gore was still a youngster and he had not invented the Internet yet, and if you wanted to read about cool things you went to a place called the library. One of the cool things to read about there, for me, was the .375 Holland and Holland cartridge, along with the rifles that chambered its Panatela of a cartridge. The descriptions were delicious…a magnum rifle firing a 300-grain bullet 3/8ths of an inch in diameter at 2700+ fps with the trajectory of a .30 06.

The .375 H&H goes all the way back to 1912, when it was developed by the great English firm of Holland and Holland. It’s still one of the best cartridges ever for hunting big beasts that snarl, roar, bite, stomp, and gore those who would do them harm. It was the first belted magnum cartridge. The idea is that cartridge headspaces on the belt (a stepped belt around the base), a feature that wasn’t really necessary for proper function, but from a marketing perspective it was a home run. Nearly all dangerous game cartridges that followed the mighty .375 H&H, especially those with “magnum” aspirations, were similarly belted. Like I said, it was a marketing home run.

As a young guy, I was convinced my life wouldn’t be complete without a .375 H&H rifle. You see, I had more money than brains back in those days. I spent my young working life on the F-16 development team, and my young non-working life playing with motorcycles and guns. I was either on a motorcycle tearing up Texas, or on the range, or hanging around various gun shops between El Paso and Dallas. In Texas, some of the shops had their own rifle range. People in Texas get things right, I think.

One of the shops I frequented was the Alpine Range in Fort Worth, Texas. The fellow behind the counter knew that I was a sucker for any rifle with fancy walnut, and when I stopped in one Saturday he told me I had to take a look at a rifle he had ordered for a customer going to Africa. He had my interest immediately, and when he opened that bright green Remington box, what I saw took my breath away. It was a Safari Grade Model 700 in .375 H&H. In those days, the Safari Grade designation meant the rifle had been assembled by the Remington Custom Shop, and that was about as good as it could possibly get.

The Model 700 was beautiful. Up to that point, I’d never even seen a .375 H&H rifle other than in books and magazines. This one was perfect. In addition to being in chambered in that most mystical of magnums (the .375 H&H), the wood was stunning. It had rosewood pistol grip and fore end accents, a low-sheen oil finish, the grain was straight from the front of the rifle through the pistol grip, and then the figure fanned, flared, flamed, and exploded as the walnut approached the recoil pad. I knew I had to own it, and I’m pretty sure the guy behind the counter knew it, too. Did I mention that the rifle was beautiful?

“How much?” I asked, trying to appear nonchalant.

“I can order you another one,” the counter guy countered, “but this one is sold. I ordered it for a guy going to Africa. I’ll order another one for you. They all come with wood this nice.”

“Has he seen this one yet?” I asked, not believing that any rifle could be as stunning. I knew that rifles varied considerably, and finding one with wood this nice would be a major score, Remington Custom Shop assembly or not.

“No,” the sales guy answered, “he hasn’t been in yet, but I can get another for you in a couple of days. Don’t worry; they’re all this nice.”

His advice to the contrary notwithstanding, I worried. This was the one I had to own. “How much?” I asked again.

“$342,” he answered.

Mind you, this was in 1978. That was a lot of money then. It seems an almost trivial amount now. The rifle you see in the photo above, especially with its fancy walnut, would sell for something more like $2,000 today. Maybe more.

“Get another one for Bwana,” I said. “This one is mine.”

“But this is the other guy’s.”

“Not anymore it’s not. Not if you ever want to see me in here again,” I said. Like to told you earlier, I was a young guy back then in 1978. I thought I knew how to negotiate. My only negotiating tool in those days was a hammer, and to me, every negotiation was a nail. You know how it is to be young and dumb, all the while believing you know everything.

“Let me see what I can do,” the sales guy said, with a knowing smile. When the phone range at 10:00 a.m. the following Monday, I knew it was the Alpine Range, and I knew the Model 700 was going to be mine. I told my boss I wasn’t feeling well.

“Another rifle?” he asked. He didn’t need to ask. He knew. We were in Texas. He had the disease, too.

In less than an hour, the rifle you see in that photograph above was mine. The guy behind the counter at the Alpine Range was good. He had already received a second Safari Grade Model 700, in .375 H&H, so the safari dude was covered. I asked to see the replacement rifle and the walnut on it was bland, straight grained, and dull…nothing at all like the exhibition grade walnut on mine. It made me feel even better.

I’ve owned my Model 700 .375 H&H Remington for more than four decades now. I’ve never been on safari with it and I have zero desire to shoot a cape buffalo, a lion, a tiger, or anything else, but I do love owning and shooting my .375 H&H. I’ve never seen another with wood anywhere near as nice as mine, and that makes owning it all the more special.

Like reading about guns? See all our Tales of the Gun stories!

Some days you just have to pick up your marbles and go home.

Some days you just have to pick up your marbles and go home.

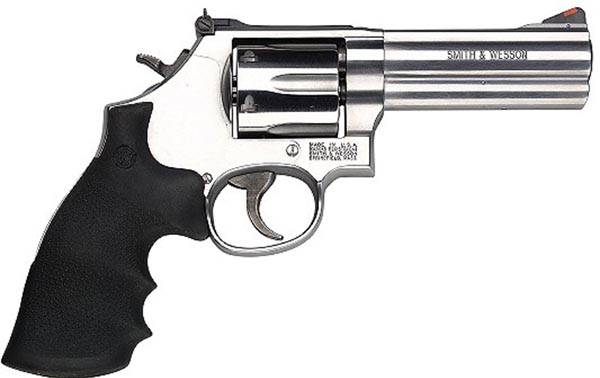

The Ruger would rust if you didn’t keep it clean and the bottles weren’t shattering enough to suit me so the next gun I bought was a stainless steel Smith and Wesson .357 revolver with a 4-inch barrel. When you pulled the trigger you could see the drum turn, the hammer draw back and flames shoot out the sides of the weapon. It was like a miniature cannon. You got dirty shooting the thing. The whole process of firing the S&W revolver satisfied me on so many levels that at this point I was perilously close to becoming a gun nut.

The Ruger would rust if you didn’t keep it clean and the bottles weren’t shattering enough to suit me so the next gun I bought was a stainless steel Smith and Wesson .357 revolver with a 4-inch barrel. When you pulled the trigger you could see the drum turn, the hammer draw back and flames shoot out the sides of the weapon. It was like a miniature cannon. You got dirty shooting the thing. The whole process of firing the S&W revolver satisfied me on so many levels that at this point I was perilously close to becoming a gun nut. For some reason, maybe it was God’s Hand, I didn’t become a gun nut. The trips out to Kitchen Creek became fewer. The ammunition got more expensive and the two pistols were packed away. It was only a few years ago that I dug the guns out. The Ruger was a mess. Rust had scarred its smooth gun-black finish and the mechanism was stuck. It took hours to get the thing cleaned up and the rest of the day to figure out how the various parts fit back into the handgrip. Being stainless, The Smith was fine, only needing a bit of oil to loosen things up.

For some reason, maybe it was God’s Hand, I didn’t become a gun nut. The trips out to Kitchen Creek became fewer. The ammunition got more expensive and the two pistols were packed away. It was only a few years ago that I dug the guns out. The Ruger was a mess. Rust had scarred its smooth gun-black finish and the mechanism was stuck. It took hours to get the thing cleaned up and the rest of the day to figure out how the various parts fit back into the handgrip. Being stainless, The Smith was fine, only needing a bit of oil to loosen things up. This Christmas CT gave me one of those heavy steel spinner targets, the kind with a large round target on the bottom and a smaller one on the top. When you manage to hit the thing the target spins around like a kinetic lawn ornament. I guess CT enjoyed our day at the range more than I did. Now she wants a Mosberg pump shotgun and one of those scary looking assault style rifles. You know, for home protection. It seems like we might end up with a gun nut in the family after all.

This Christmas CT gave me one of those heavy steel spinner targets, the kind with a large round target on the bottom and a smaller one on the top. When you manage to hit the thing the target spins around like a kinetic lawn ornament. I guess CT enjoyed our day at the range more than I did. Now she wants a Mosberg pump shotgun and one of those scary looking assault style rifles. You know, for home protection. It seems like we might end up with a gun nut in the family after all.