By Joe Gresh

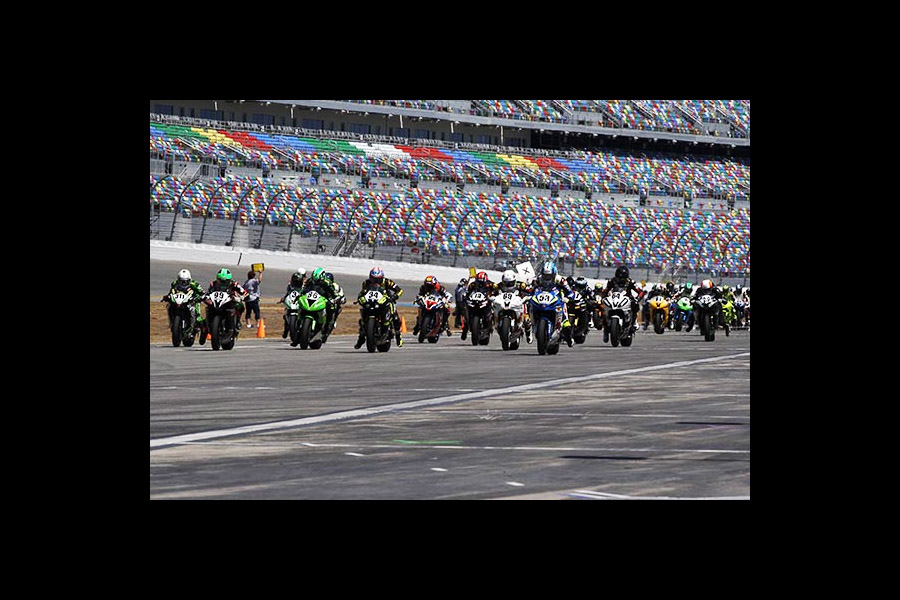

See that gap? That narrow space between the semi-truck hauling 20-foot long, 6-inch diameter solid aluminum rods and the BMW M6? I’m taking it, man, riding the horn button and twisting the throttle: zoom-zoom. See that intersection? The one with a whirlpool of scooters, three-wheeled single-cylinder diesel trucks and at least a hundred cars spinning left leaving eddys of pedestrians lapping at the edges? I’m a Hurricane Hunter riding straight into the maelstrom buffeted from side to side, tip-toeing around, swerving, cussing, sweating and focused, man, focused.

China’s city traffic requires all your intensity, taxes all your ability and is like nothing I have ever seen on the planet. There is no respite. There is no pause, You must lock on and track hundreds of individual trajectories from every point on the compass, constantly. Insane traffic scenarios unfold at a lightning pace, there’s no time to marvel at the stupidity. There’s only time to act.

The chaos is cultural: Chinese motorists drive like they’re riding a bicycle because they were only a few years ago. In less than one generation the Chinese have gone from pedals to 125cc Honda clones to driving millions of air-conditioned automobiles on surface streets designed for a sleepy agricultural nation. At any given moment dozens of traffic rules are being broken within 50 feet of your motorcycle. It’s a traffic cop’s dream.

Except that there aren’t any. For a Police State there are not many police in China. I’ve ridden entire days and not seen one Po-Po. My Chinese friends tell me the police show up for collisions but otherwise stay low-key. Because of this hands-off approach stop signs are ignored. Red lights mean slow down. You can make a left turn from the far right lane and no one bats an eye.

China uses the drive-on-the-right system but in reality left-side driving is popular with large trucks and speeding German sedans. Get out of the way or die, sucker. Painted lane-stripes are mere suggestions: Drive anywhere you like. Of course, sidewalks and breakdown lanes are fair game for cutting to the front of the cue.

China’s modernization process has happened so fast that the leap from two-wheeled utility vehicle to motorcycles as powersports fun never really occurred. In China there are millions of people riding motorcycles but relatively few motorcyclists.

If the cars don’t get you there are other strange rules that serve to dampen the popularity of Chinese motorcycling as a hobby. Motorcycles are banned on most major toll ways between cities. Law-abiding motorcyclists are shunted off to the old, meandering side roads. Which would be fun if they weren’t so infested with heavy, slow moving semi-trucks and near certain construction delays. In practice, since tollbooths have no ability to charge motorcyclists, Chinese riders blow through the far right lane, swerving to avoid the tollgate’s swinging arm. Ignore the bells, shouting and wild gestures of the toll-takers and roll the throttle on, brother.

Being banned from the highway is not a deal breaker, but being banned from entire cities is. In response to crimes committed by bad guys on motorcycles many cities remedied the problem by eliminating motorcycles altogether. Sales of new motorcycles in these forbidden cities is non-existent.

Rules designed to discourage motorcycling abound. Vehicles over 10 years old are not allowed to be registered, thus killing the used and vintage scene. Gasoline stations require motorcyclists to park far from the gas pumps and ferry fuel to their bikes in open-topped gas cans. Add to that the general opinion of the public that motorcycle riders are shifty losers too poor to afford a car.

So why do Chinese motorcyclists bother to ride at all? It’s not the thrill of speed; 250cc is considered a big bike in China and it’s really all you need to keep up with the slow moving traffic. I’ve spent a lot of time with Chinese riders and even with the language barrier I get that they ride for the same reasons we do: The road, the rain, the wind. After being cooped up in a high rise apartment (very few Chinese live in single-family homes) I imagine the wide-open spaces between crowded cities must seem like heaven. They did to me. Chinese motorcyclists and Low Riders ride a little slower, taking long breaks to smoke a cigarette, drink in the scenery or just nap. Every motorcyclist you meet is instantly your dear friend because we share this passion and despite all the minor regulatory hassles everybody knows love conquers all.

More epic motorcycle adventures? You bet!

Help us bring you more stories: Please click on the popup ads!

Want to read all about the China ride? Pick up a copy of Riding China!

On our return ride it was time to make food choices again. Choosing to stop at the first crowded place made sense. We soon discovered an establishment and radioed to each other that this looked acceptable. Instantly, all eyes were upon us as we sat down in a three-walled, white-paint-chipped open room. One thing we found in Vietnam wat that when you order food, you don’t always get what you asked for. Often you get what they have, even though they will nod their head to your request while saying “ya ya ya.” In this restaurant we kept it simple and ordered pho.

On our return ride it was time to make food choices again. Choosing to stop at the first crowded place made sense. We soon discovered an establishment and radioed to each other that this looked acceptable. Instantly, all eyes were upon us as we sat down in a three-walled, white-paint-chipped open room. One thing we found in Vietnam wat that when you order food, you don’t always get what you asked for. Often you get what they have, even though they will nod their head to your request while saying “ya ya ya.” In this restaurant we kept it simple and ordered pho.