By Joe Gresh

In 2019 we booked a campsite at Chaco Canyon in northern New Mexico. Chaco Canyon was a fairly large Native American city that served as the capital for the Chaco people a thousand years ago. Strung out along the canyon within walking distance of each other there are several large, condominium-style structures, some reaching 5 stories high and all of them with courtyards, living areas, kivas, and storage rooms. The condos were built with fantastically intricate stonework consisting of millions of large and small stones. Chaco society was well organized and their mathematics and architectural engineering were well advanced, as it would need to be in order to produce such big, complex buildings.

Also in 2019 the plague hit and Chaco Canyon was closed to visitors, so we never made it to the campground. The same thing happened in 2020, so we missed Chaco that year and instead spent our time arguing on the Internet about masks and vaccines with medically-trained basement dwellers. In 2021 we had a reserved campsite near the cliffs of the canyon and not long before we were due to arrive the cliff calved, covering our campsite with boulders. The campground was closed in order to clean up the rubble. The section where we were booked is still closed.

In 2022 we again called the ranger station at Chaco Canyon and reserved a site. All looked well in 2022 but a day or two before we were to leave CT came down with a nasty cold and we decided camping would be no fun with one of us sick in bed. Reluctantly, we cancelled our reservations yet again. Our efforts to see Chaco Canyon seemed cursed. We decided to try again in 2023 and figured March would be a good time to go. We wanted to avoid the hot summer months. Building up to March everything was going swimmingly; this would be the year we finally made it to the historic Native American site.

And then the rain started. We watched the weather reports coming in from Chaco Canyon: rain, snow, hail. It rained at Chaco Canyon every day the week before we were to go. All roads leading to Chaco Canyon involve quite a few miles of dirt. The rougher, south entrance to the canyon was closed due to the muddy road being impassable. We didn’t care: we were going to Chaco even if we drowned in mud. Farmington was our staging area for the camping expedition and we drove in spotty rain all day to get there. Turning north out of Albuquerque on Highway 550 we stopped for gas. While I was filling the gas tank it started snowing. Then the wind picked up to a brisk gale. The last 50 miles to Farmington were in a drizzly rain mixed with sleet. We made it to our motel where it rained all night long. The normally well-maintained north entrance road to Chaco Canyon was starting to look a bit iffy.

The next day was overcast and rain threatened, but the morning was drama free with only a light dusting of snow on our way to the entrance to Chaco. If you’re going to visit Chaco Canyon you’ll no doubt read horror stories about how rough the road is leading to the canyon. Keep in mind the people fretting about the road are driving giant RVs held together with staples and chewing gum. You may lose a kitchen cabinet or an ill-considered propane tank. If you are driving a car or truck you’ll be fine. Unless it has rained five days straight before you arrived.

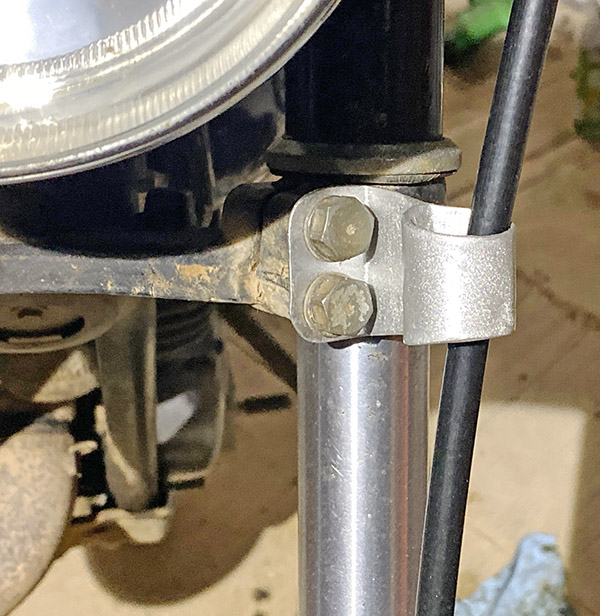

Turning off Highway 550, the first 8 miles to Chaco Canyon are paved and then the road turns into wide, graded dirt. This section was very muddy and CT put her Jeep in 4-wheel low and locked the front and rear differentials. She couldn’t go very fast because the Jeep wanted to spin into the ditch at the slightest sign of ham-fisted steering. Down hills were exciting; the Jeep kind of drifted to the bottom in a semi-controlled slide. The mud wasn’t deep, only a few inches, but it was like driving on ice covered with ball bearings and oil.

We saw two other vehicles on our 23-mile ride and one of them was stuck in a ditch. CT is a big believer in recovery gear so she has straps and chains onboard at all times. Unfortunately this means we have to stop and help people who get stuck in a mud bog. The guy was so glad to see us. We came to a gentle stop 30 feet past the deepest part of the mud hole. “You got a rope?” I asked Mr. Stucky.

“No I sure don’t,” he said. I gave a dejected look at the mud.

“Do you guys have anything we can use?” he asked.

“Yeah, we got something.” I stepped into the mud and pulled CT’s clean ARB tow strap out of its clean zipper case.

“I think if you can pull me back onto the road I’ll be ok. I was going too fast and spun out.”

I was only half listening to Stucky. All I could think of was that this means we have to get CT’s ARB tow strap muddy with this sticky goo and then I’ll have to clean it later.

Walking was hard due to the mud sticking to our boots and the slipperiness, but we managed to connect our nice, clean, tow strap to Stucky’s SUV and pulled his rig backwards towards a less muddy area. Stucky’s mini SUV didn’t want to leave the ditch and it crabbed along spinning wheels and slinging mud for 100 feet before it popped out of the rut and onto what passed for the road. I started to wind up the tow strap when Stucky, sensing my disappointment, said, “Here, let me get that. No need for you to get any muddier.” I was muddy already, but I handed Stucky the strap. I wanted him to feel like he had a stake in not getting stuck again. As Stucky coiled the ARB tow strap mud oozed between each wrap. We were only a few miles to the campground from this point.

Once you make it to Chaco Canyon the roads are paved so we had no trouble finding the ranger station or our campsite. The place was nearly deserted. Stucky’s little teardrop trailer was the only other camper at Chaco that day. Fast moving clouds scudded from west to east bringing alternate periods of sunshine, snow, rain and hail. During a sunny spell we set our Campros tent up on the nice, raised tent platforms provided to each camping spot. The raised tent spots are built from pressure treated 8×8 beams laid out in a square totaling 14 feet by 14 feet. The squares were filled with nice, soft dirt and we were damn near glamping, you know? I guess if I were more observant, the tie down clevises screwed into the pressure treated lumber would have given me a hint about wind speeds in Chaco Canyon.

We watched the looping, 15-minute Chaco Canyon video at the ranger station’s little movie theater and then decided to set up and get our junk sorted out. It was windy and cold but we had plenty of warm clothing to wear. CT brought along 6 jackets, 7 hats, and 3 duffle bags full of thermal underwear. The tent was heaving and snapping; it took two people to hold it still long enough to assemble the thing. The temperature started dropping as soon as the sun went down. A campfire was out of the question in this wind so we made our bed, ate a little cold-cut snack for dinner, drank hot, Dancing Goats coffee and sat at opposite sides of the tent holding the corners down.

Moving all the heavy gear to the perimeter of the Campros tent seemed to keep it from blowing over. We were able to snuggle together in the sleeping bag and kept from freezing, which was the whole reason I wanted to go camping with CT in the first place. We saw 27 degrees that night and the wind never stopped blowing. The next day was slightly warmer and the sun was peeking out from the clouds, but it was even windier.

Due to the weather all the ranger presentations were cancelled. We signed up for a Chaco tour led by a Navajo business called Navajo Tours USA. We used these guys before at the Bisti Badlands and they are great fun. The tour started at 10 a.m. and we went to each condominium and wandered around while our guide told us about the different stone patterns and construction details of the buildings. Usually Chaco great houses have a basement level and many of the places we were walking had filled in with dust and sand over the preceding thousand years.

Above the basement there were three or four stories. Each level was accessed by a ladder from the level below. This system continued on until you reached the roof. The floors were made from large wood beams, called vigas in Spanish. Over the beams were placed smaller sticks and an adobe floor. The vigas hauled to Chaco came from the mountains many miles away. I figure there must have been some sort of money or economy that would have allowed workers to drag those beams and still be able to sustain a living wage.

The walls of the condos were fairly thick. Starting at the bottom the walls were three feet thick or more. The walls tapered as they rose, becoming thinner floor-by-floor. Top-floor walls might only be one foot thick. Originally, the inner walls were plastered smooth with some sort of lime coating. In a few spots you could still see the factory stucco. There were windows that let light into the rooms. Inner rooms were dark but they had openings that aligned with outer windows that allowed outside light to penetrate several rooms deep. The outside windows had wooden shutters for winter use.

The winds, strong already, were picking up and at times you’d be blown off balance. Each gust brought a stinging blast of sand and my eyes were getting full of grit. The Chaco people situated their buildings according to astronomical events. Usually one long, straight wall aligned with the rising sun at the solstices. Sometimes the wall pointed towards a particular star. The building was a giant calendar.

There is a lot more to the Chaco culture, the long, straight roads they built, where their food came from, and why the city was abandoned after only a few hundred years, but it was late in the afternoon and getting colder. The wind was so strong I couldn’t hear our guide very well. Light hail was falling and wisps of snowflakes juked and stutter stepped in the air. As much as I enjoyed the lecture I was glad when it was over. I like it outside but there is such a thing as too much outdoors. We went back to the campsite to have a little hot tea.

Camp was a disaster. Our Campros tent looked like a downed weather balloon. Tent poles had broken, stakes were pulled out and the rain fly was detached and flapping in the breeze. Inside the tent everything was covered in dirt blown in through the screened roof. We tried to get the tent propped back up but when I pulled on it things started ripping. We managed to get the rain fly back over the wreckage and placed large boulders on the corners to hold it in place. It was snowing again. There was nothing to be done with the wind blowing so we went to the ranger station and loitered. I bought a ceramic coffee cup with a Chao Canyon logo; it was good to be out of the wind.

By 7 p.m. the wind eased up a little and we went back to camp to try to salvage what we could. Our first chore was emptying the Jeep before it got dark. The idea being if we couldn’t fix the tent we could retreat to the Jeep and sleep in the back. Sure it would be cramped but at least we had a heater in the car. And the car wouldn’t blow over. Maybe.

We managed to get the tent propped back up with the short, broken poles. The short poles made every other dimension wrong. The main ridge pole had a huge S curve and there were wrinkles all over the place. It wasn’t a thing of beauty. Besides the broken poles, the upwind corners were ripped where the tent stake loops attach. We propped heavy stuff in those corners to hold the tent’s shape. Next we cleaned up all the sand as best we could and finally got organized enough to have another cold dinner and hot coffee. A campfire was out of the question because neither of us wanted to bother. In retrospect, when we left that morning we should have lowered the tent and placed rocks on the rain fly to hold it down. I believe it would have survived without a problem. I have no gripe against the tent: it went through a hurricane.

The jury-rigged tent stayed up all night long and by morning the sun was out and it was a relatively warm 40 degrees. Blue sky shined in through our open tent door and the wind was a gentle breeze. If our reservations were made just two days later we would have had a totally different feel for Chaco Canyon. It would have been nice Chaco Canyon instead of mean Chaco Canyon. The muddy road had dried up and was now passable by standard automobile. The campground started filling up as we packed our gear. Old Joe would have folded up the battered tent with the broken poles and torn corners, taken it home and stored it for 43 years thinking he was going to fix it one day. New Joe tossed it in the dumpster.

Those long-ago Chaco people had it much better in their thick stone buildings. Maybe the climate was different then, but I suspect not that much different. And it was an unusual weather pattern that saw all the other campers cancel their reservations leaving only Stucky, his dog and us in the entire joint. The campgrounds were nice with clean bathrooms, flush toilets and heat, but no showers. We never did get to see all the buildings because it was so windy and cold. CT and I want to back to Chaco Canyon and explore more but maybe next time we’ll go when the weather is more clement.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

You know what to do: Please click on the popup ads!