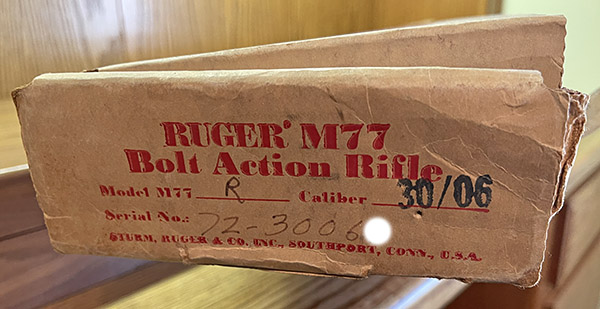

By Joe Berk

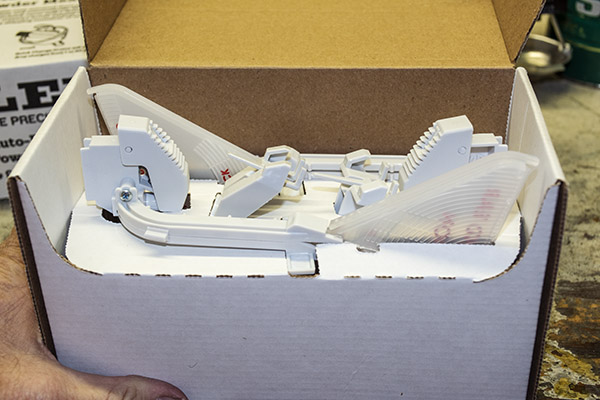

I promised an update on my Smith and Wesson 9mm Shield, and this is it. I’ve put 2,500+ rounds through the Shield (all reloads with different bullets and powders). Until I recently took my Shield to good buddy TJ, I was growing increasingly dissatisfied with the pistol’s frequent failures to extract, and I wasn’t alone. If you Google “failure to extract” and “Smith and Wesson Shield” you’ll find a lot of people are having this issue. My problem is in the rearview mirror, though, and my Shield is 100% reliable now. That’s because of TJ. I’ll get to that in a minute.

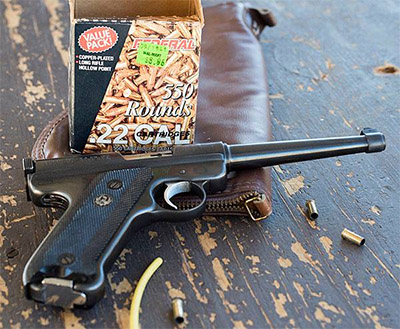

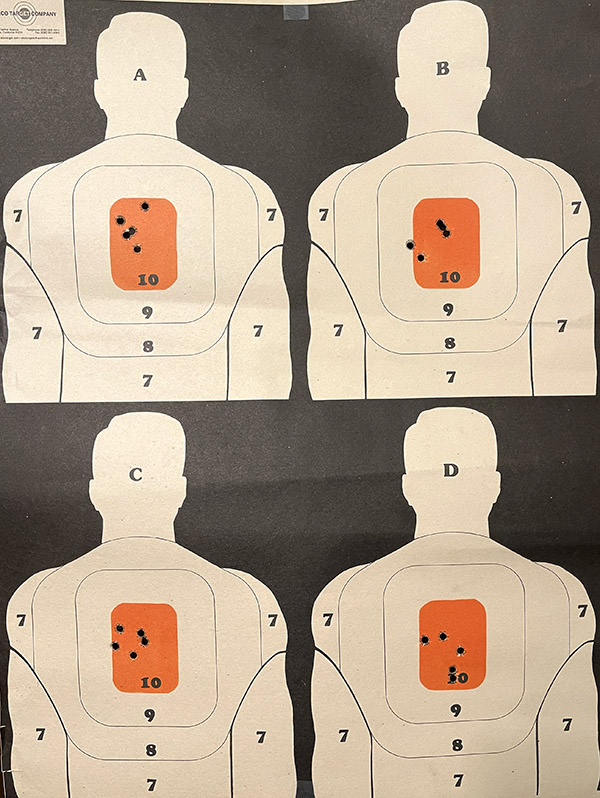

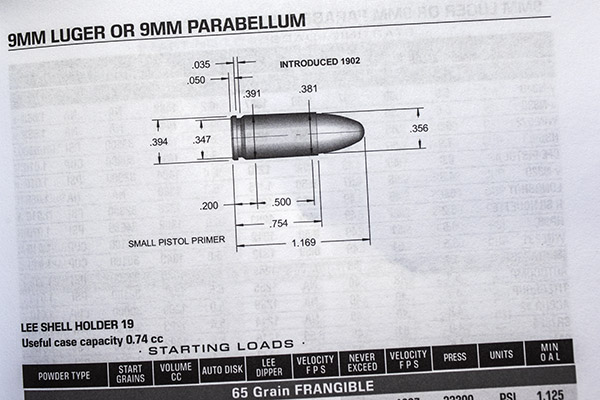

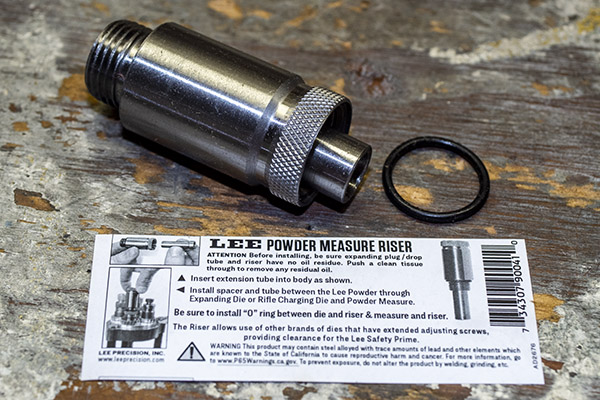

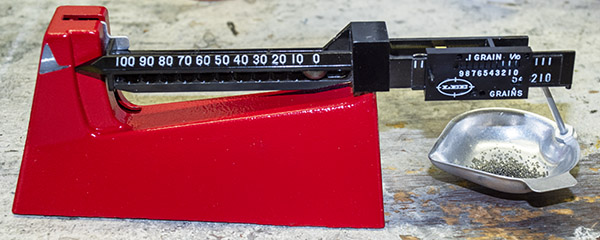

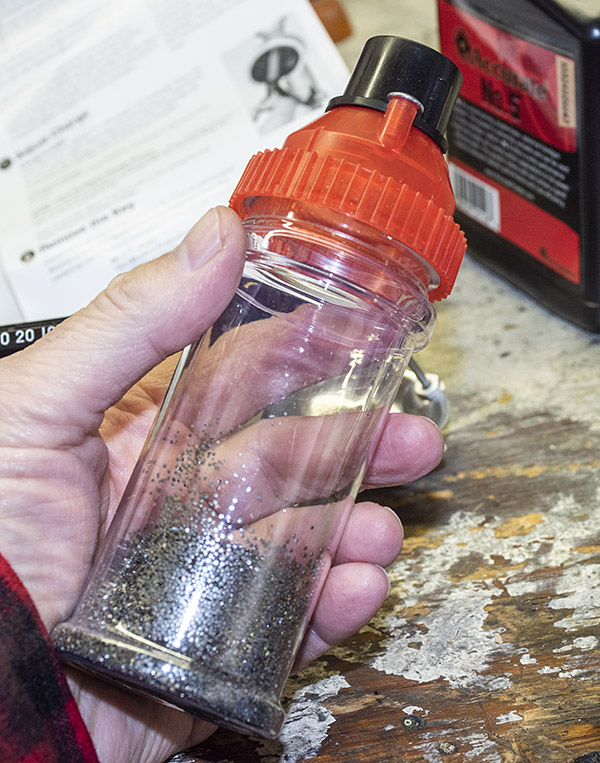

That target above? It’s 50 rounds at 30 feet through my Shield, shooting offhand. If you’re a reloader, here are the load specifics:

-

-

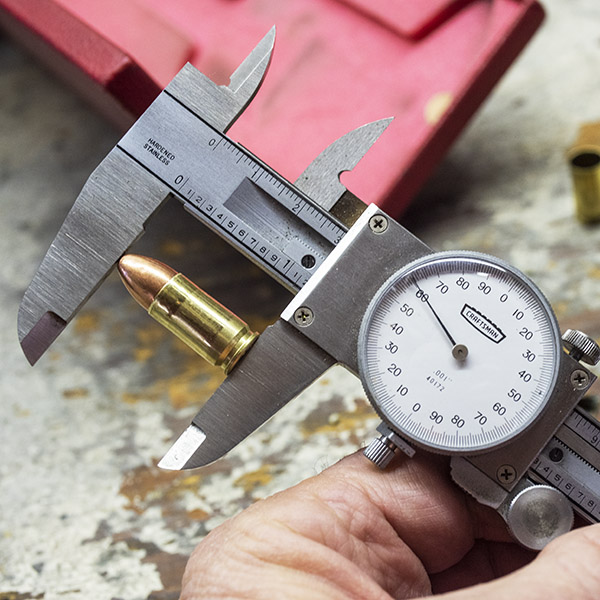

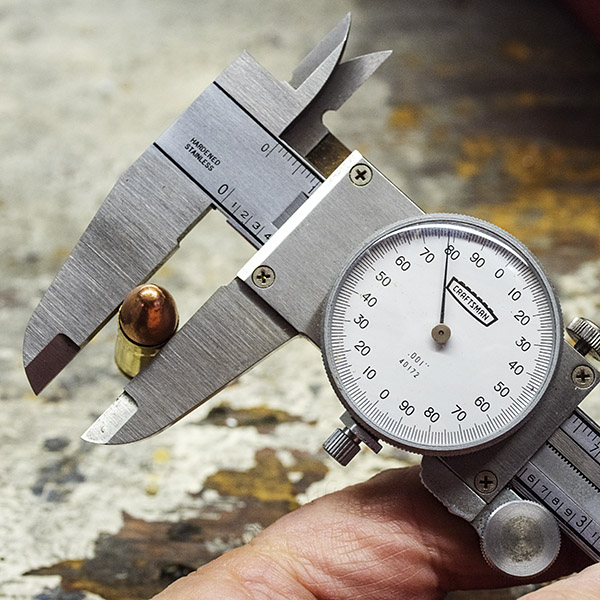

- Jim Gardner 125 grain powder coated roundnose bullets (Jim sized these to 0.356 inch, which is his standard bullet).

- Cartridge overall length 1.145 inches.

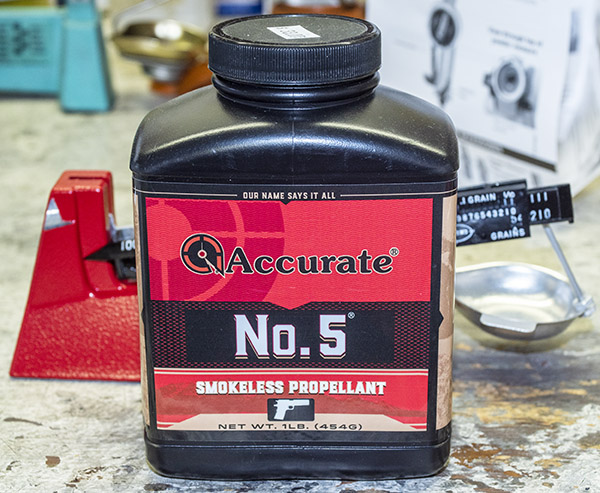

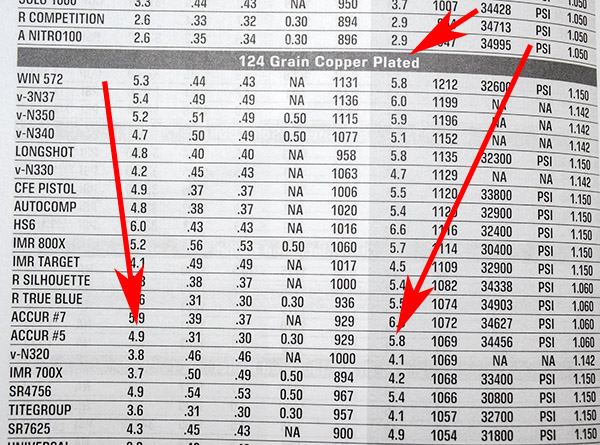

- 5.4 grains of Accurate No. 5 propellant.

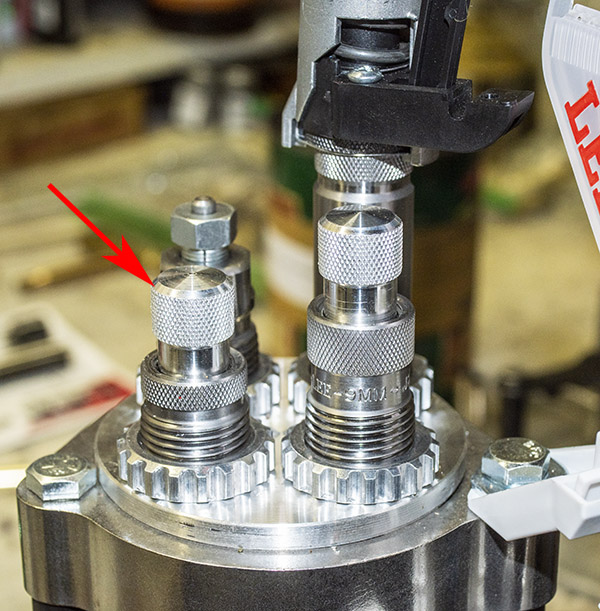

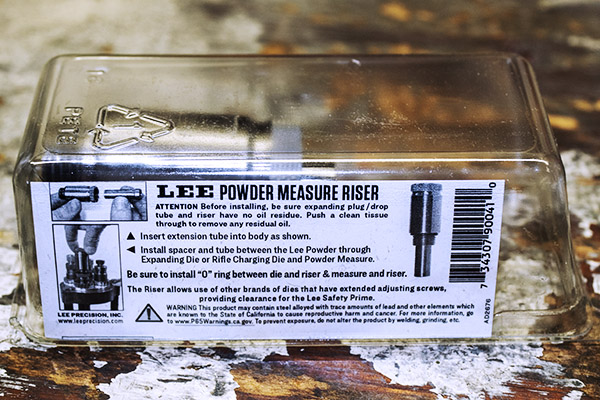

- Lee factory taper crimp (light crimp; see below).

- Ammo loaded on Lee Classic 4-Turret press.

- Mixed brass.

-

Ordinarily, I tailor a load to the handgun, and I thought I would be able to do that relatively easily with the Shield. I found that not to be the case. The Shield seemed accurate enough with nearly every load I tried, but nearly all had reliability issues. On the low end, the lighter loads didn’t have enough energy to cycle the action (a common enough problem on compact semi-autos). Light, mid range, and hot loads all gave the Shield extraction issues. The Shield experienced a failure to extract about every other magazine. It was very frustrating. I scoured the Internet forums for this issue and the opinions were all over the map. Here’s a smattering of the drivel I found:

-

-

- Don’t use Winchester ammo because the rims are smaller (I measured them; that was baloney).

- Don’t use cast bullets because they hang up (I knew that was baloney).

- Don’t shoot aluminum ammo (which I never do, anyway).

- Don’t shoot 115-grain bullets.

- Don’t shoot 125-grain bullets.

- Don’t shoot 147-grain bullets.

- Clean your gun after every round (seriously?).

- Don’t limp wrist your gun (again, seriously?).

- Don’t do this, don’t do that, don’t do this other thing…

- Do this, do that, do this other thing…

-

It was all written by people who apparently love the sound of their keyboards clacking. None of it was useful information. I felt stupid for wasting my time reading it.

Help us keep the content coming: Please click on the popup ads!

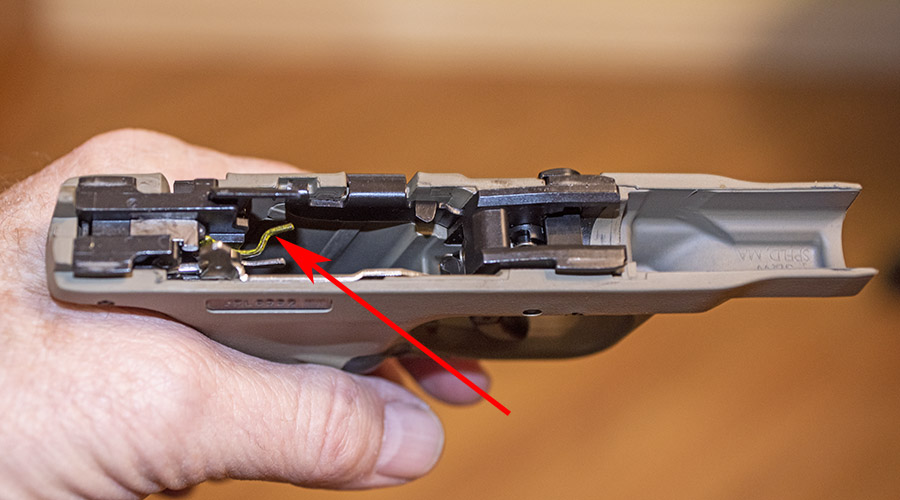

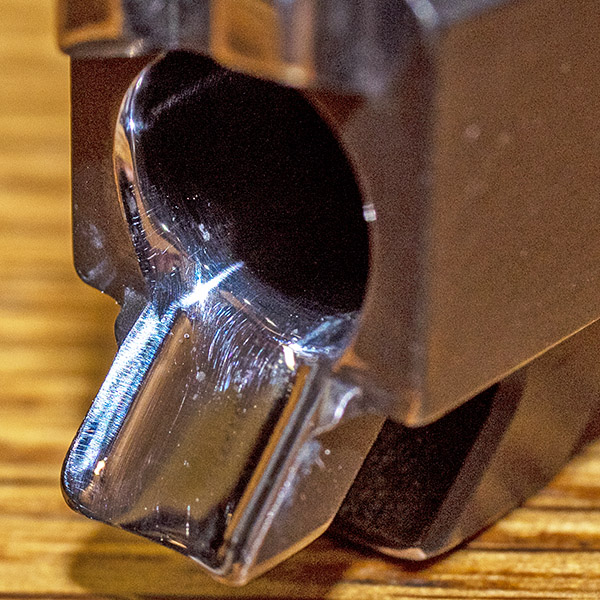

What I found was that the extraction problem occurred more with powder coated bullets than either plated or jacketed bullets. Other than that, there wasn’t a lot of correlation between any of the load variables I could play with and the gun’s failure to extract propensity. Then, during one range visit when I had a failure to extract, I fell back on my failure analysis background. I put the loaded gun down on the bench (being careful to keep it pointed downrange) and took a photo with my iPhone.

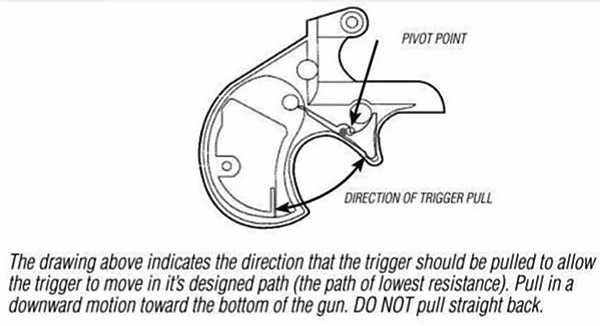

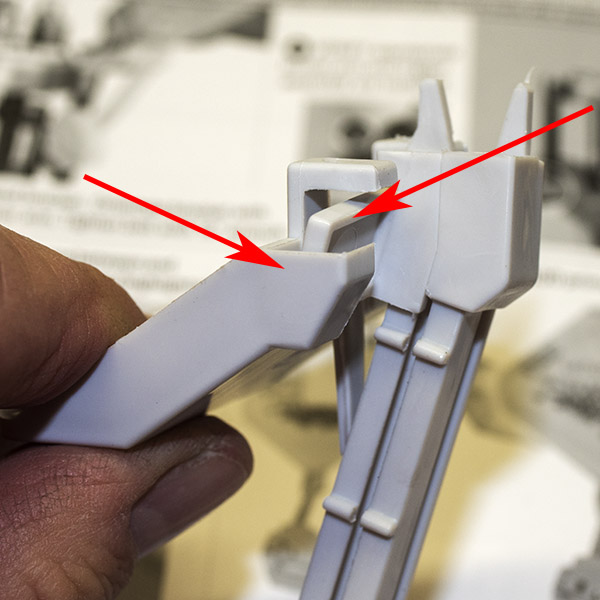

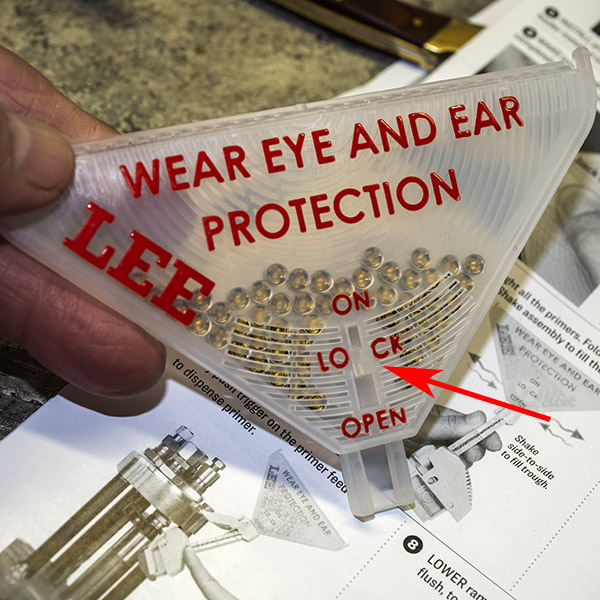

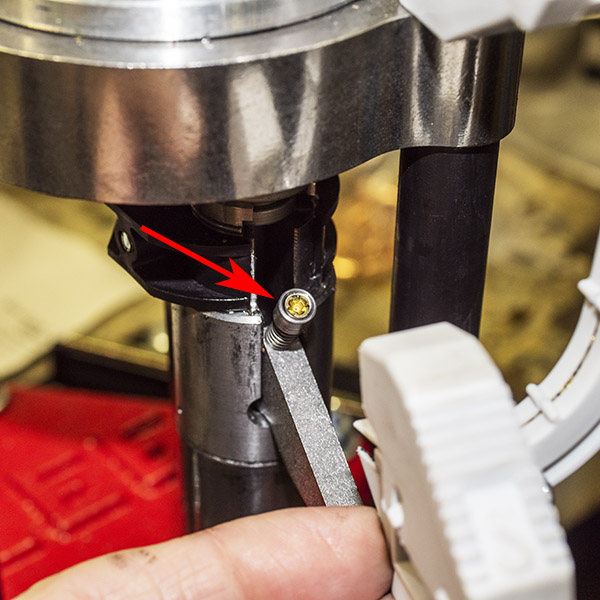

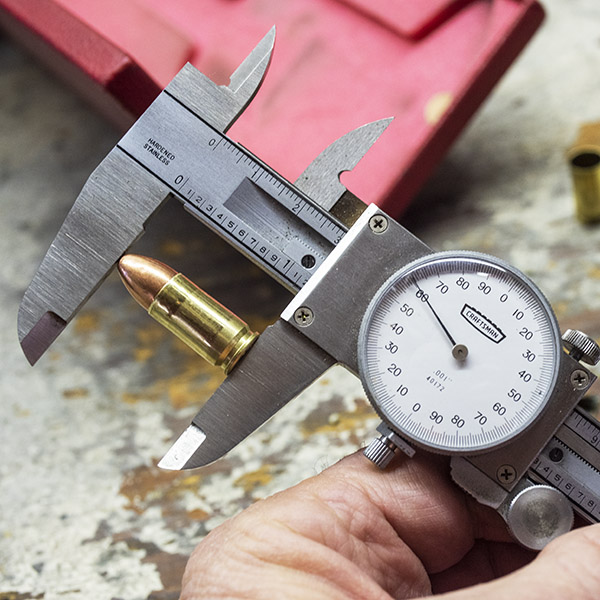

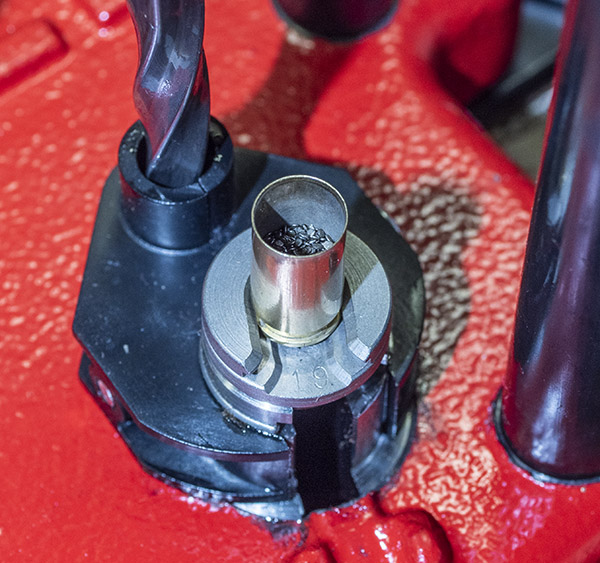

Wow. How about that? It was apparent that the case being extracted was hanging up on the case mouth of the round still in the magazine, and it was a strong enough obstacle to pull the extractor off the rim. This brought up a lot of questions in my mind centered on the crimp and the bullet. The Gardner bullets have a slight ramped step just north of the crimp. And when I crimp a bullet for a semi-auto, I put a slight taper crimp on it with the Lee taper crimp die. I want enough of a crimp to remove the case mouth flare (part of the reloading process to assure the bullet will enter the case mouth without shaving lead or copper), and enough to assure the cartridge will chamber easily. Maybe I didn’t have enough crimp, I thought, and that was causing the case being extracted to hang up.

I examined my ammo and I thought it looked good (actually, I thought it looked great; like most reloaders, I enjoy looking at my finished ammo). But, to make sure, I loaded another box with as much taper crimp as I could get out of the Lee die. Lee is right when they say their taper crimp die makes it impossible to deform a case: I put a very pronounced crimp on all the cartridges in the next box of ammo. But that wasn’t the answer, and it created a new problem. With a semi-auto like the 9mm or the .45 Auto, the cartridge headspaces on the case mouth. When I used a more pronounced crimp, I started getting misfires. The rounds were going too far into the chamber, and the firing pin wasn’t igniting the primers reliably. Nope, more crimp wasn’t the answer.

At this point, I was getting a little frustrated. All these problems aside, I wanted to like my Shield. I wanted to use it as my concealed carry weapon, so I needed the thing to be reliable. Faced with this issue, I knew it was time for what works every time: A visit to TJ’s Custom Gunworks.

TJ examined the Shield. He observed that the magazine positions the first cartridge in the magazine unusually high in the gun, and that was probably aggravating the failures to extract. But there’s not really anything you can do about that. It’s the gun’s design. It is what it is.

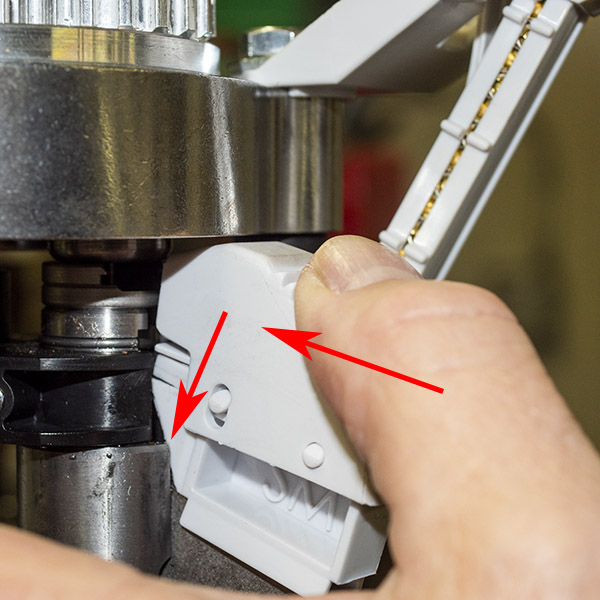

TJ then took a look at the extractor. It was pretty dirty with combustion residue, but he felt it should work. TJ, honest as always, told me he could polish the ramp and the chamber (they come from the factory pretty rough), but he didn’t know if that would fix the failures to extract. I asked TJ to proceed.

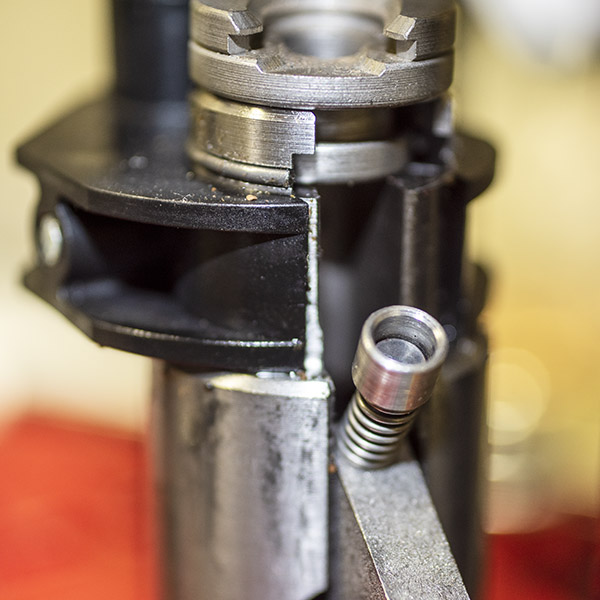

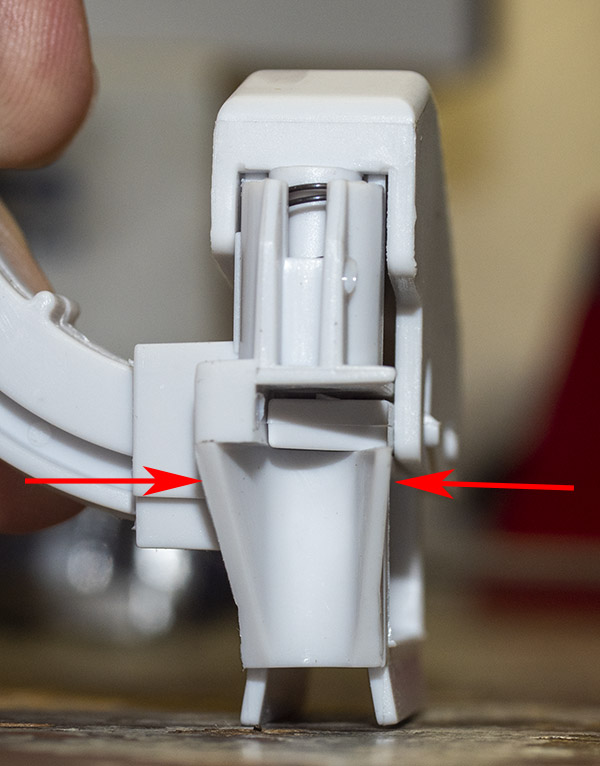

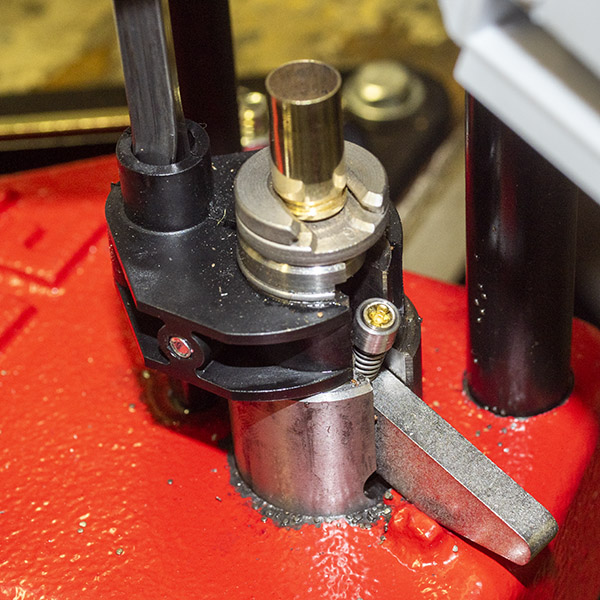

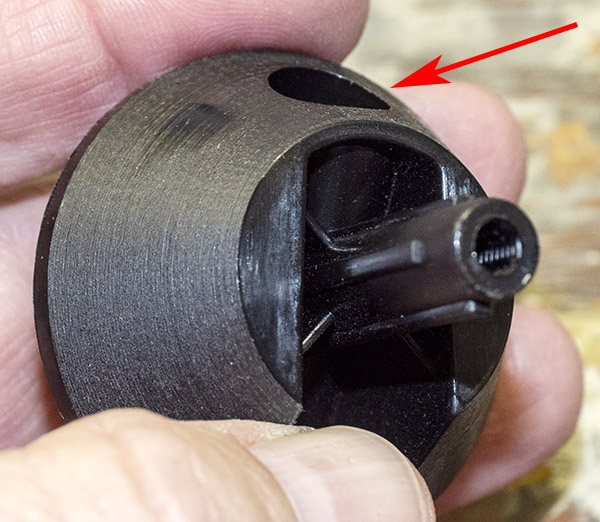

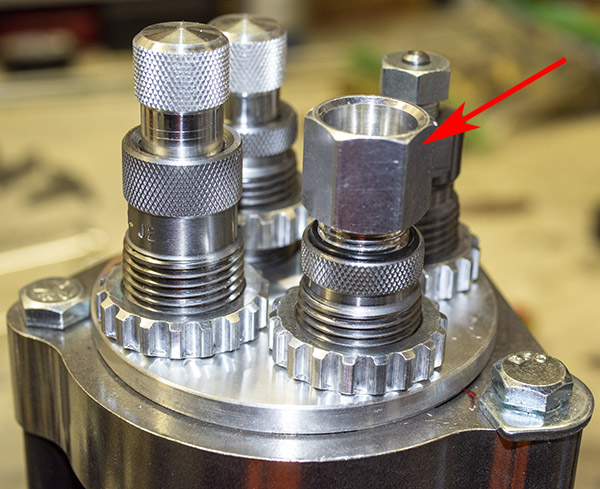

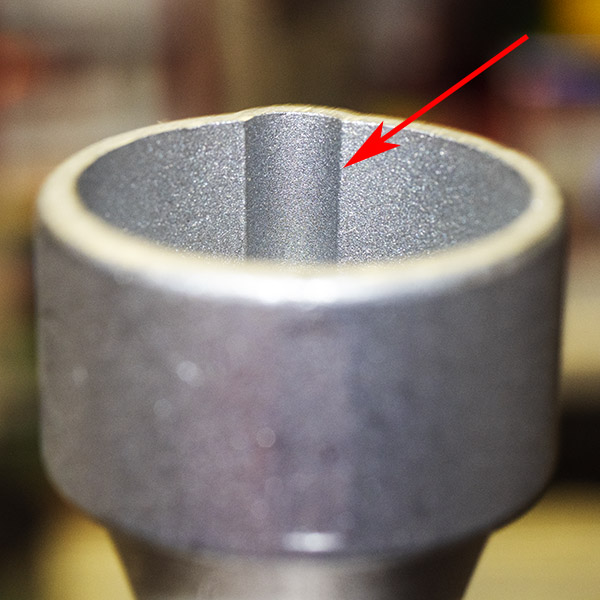

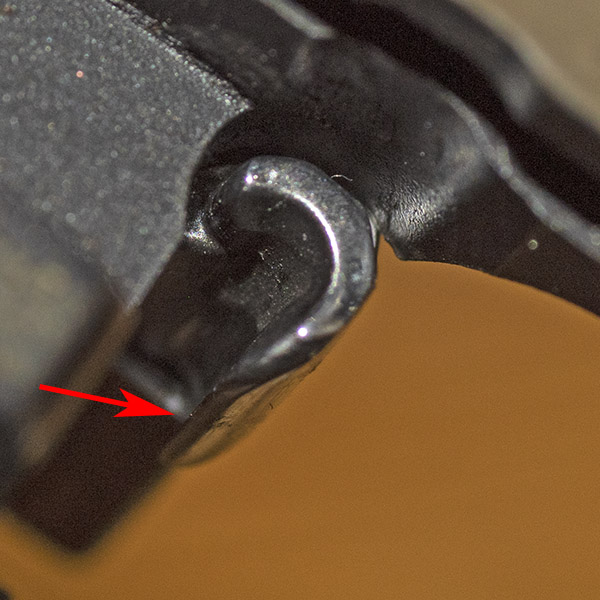

Here are a couple of photos of the chamber and the ramp as they come from the Smith and Wesson factory. The Shield always fed and chambered reliably; it was only the extraction that was an issue. TJ explained that if the chamber is rough, it can hang on to the fired case as it is being extracted. I’ve experienced that on other guns. The Shield’s chamber and its ramp looked about like I’d expect them to look on a mass-produced pistol, which is to say not very good. I asked TJ to work his magic on both the ramp and the chamber.

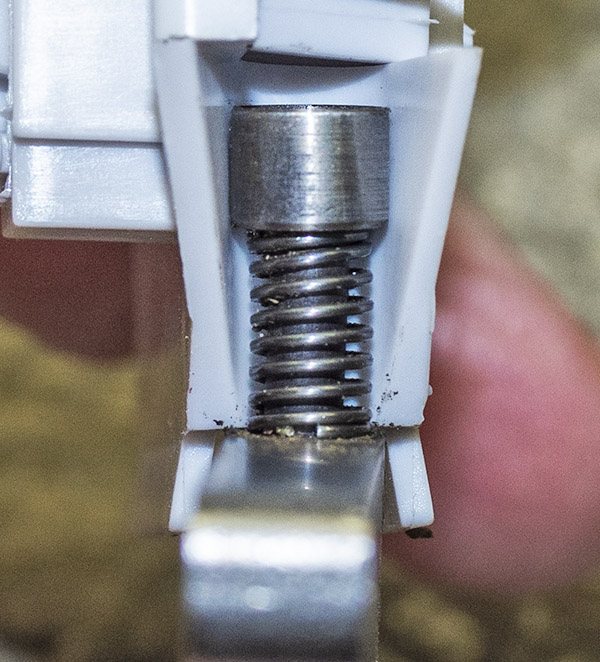

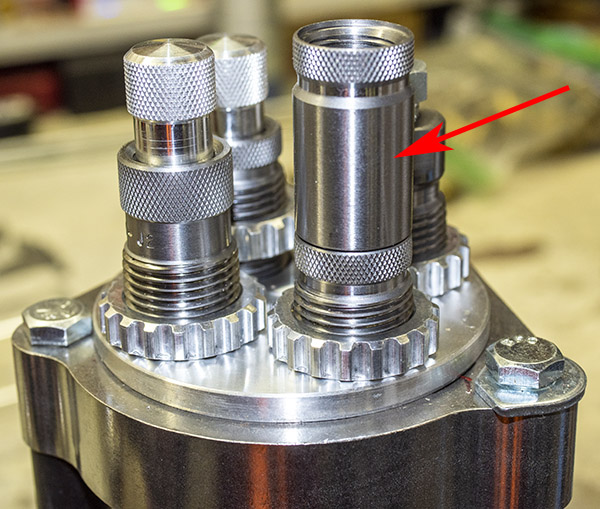

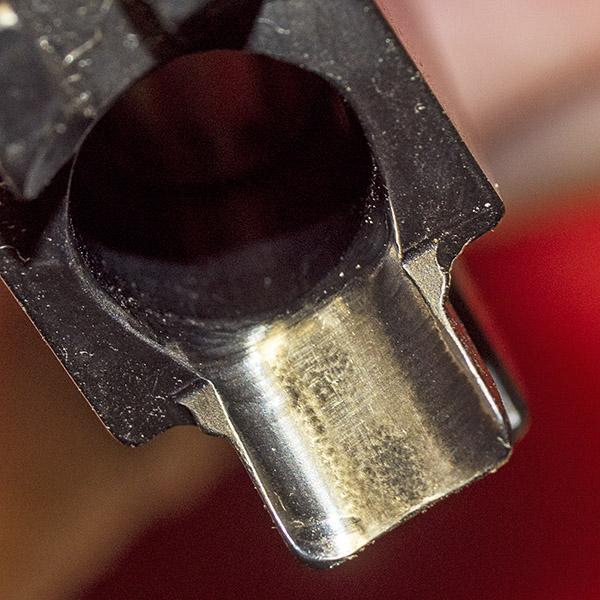

TJ did his usual excellent job, and here’s what things look like now.

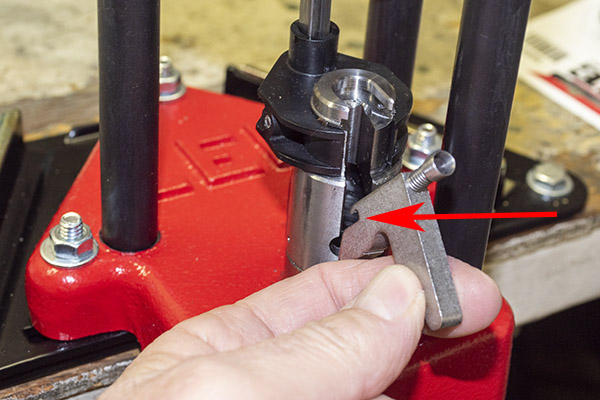

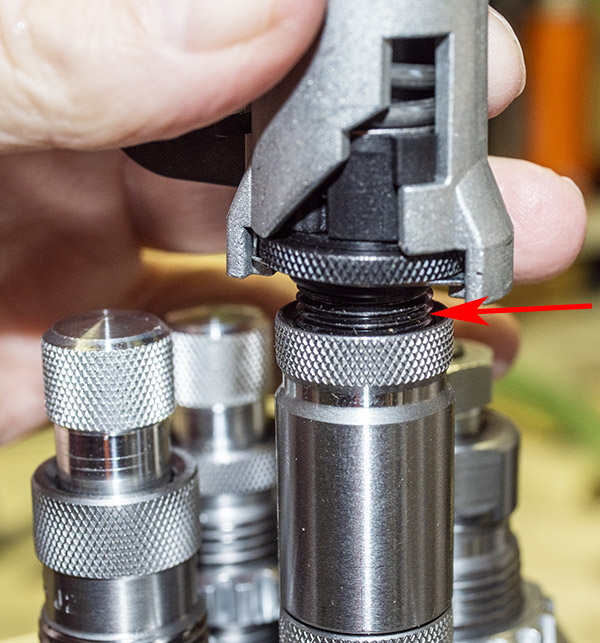

TJ told me he also put a slight undercut on the extractor to allow it to get a better grasp on the case rim.

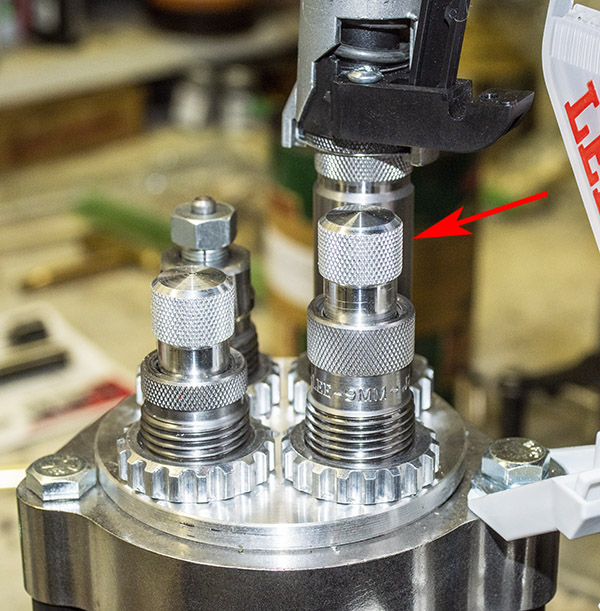

I picked up my Shield a few days later and went to the range that afternoon. The Shield is now what it is supposed to be. You saw the target at the top of this blog. I fired 50 rounds without a single failure to extract and eject. The gun just feels a lot smoother and slicker now. My Gardner bullet and Accurate No. 5 load is perfect. And the recut extractor drops the cartridges in one nice small pile on the floor behind me. Wow. I’m impressed. Then, just to make sure (and because I was having so much fun) I fired another box of 50 rounds (again, with ammo loaded on the Lee Classic Turret press using the load at the top of this page).

The Lee Classic Turret press does a magnificent job, and now, so does my Smith and Wesson Shield. It’s the way the pistol should have come from the factory.

It’s bothersome that most of my recent gun purchases have required additional work to get them to perform the way they should. In my former life as an aerospace manufacturing guy, I used to manage organizations with machine shops. I know it would cost a little more for the gun companies to do the kind of things TJ did to my Shield (and several other guns, for that matter). I wish the gun companies would do that; they ought to just hire TJ as a consultant (he knows what they need to do). The bottom line here? If you have a Smith and Wesson Shield and you want it to be what it is supposed to be, get in touch with TJ.

There are a lot of things I like about the Shield. Accuracy and illuminated sights are at the top of the list. You can get a feel for its accuracy from the targets shown here. None of this was bench rested; it was all shooting offhand on an indoor range with banging and clanging and brass flying all around me.

I found that after firing a a box of ammo, gunshot residue tends to occlude the sides, front, and rear of the front sight, and that causes the red to glow a lot less. But that’s a minor point. The Shield’s high visibility sights are great.

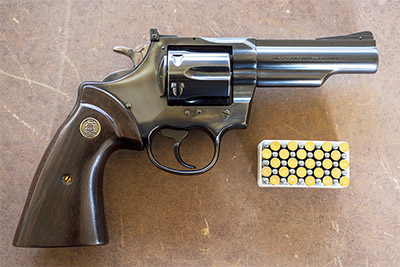

I bought a Bianchi leather holster for the Shield. It’s similar to the Bianchi I use with my Compact 1911. When I put the Shield in its holster I was surprised: It’s really not any smaller than my Compact 1911. It’s a bit narrower, but by the time both guns are holstered, the overall width is about the same. Where the Shield has a clear advantage, though, is weight. And even though the Shield with its polymer frame is much lighter than the Compact 1911, the recoil is quite a bit less than the .45. Now that the Shield has been made more reliable by TJ, it will make a good concealed carry gun. Incidentally, TJ worked his magic on my 1911, too. It’s one of the most reliable handguns I’ve ever owned.

Never miss an ExNotes blog: