By Joe Berk

Time flies when you’re having fun. It’s hard to believe it’s been a dozen years since I first visited Zongshen for CSC Motorcycles, and when I did, the RX3 wasn’t even a thought. I went to Zongshen looking for a 250cc engine for CSC’s Mustang replica (the photo above shows CSC’s Mustang and an original 1954 Mustang Pony). CSC’s Mustang replica had a 150cc engine and some folks said they wanted a 250, so we went hunting for a 250cc engine.

The quest for a 250 took me to a little town called Chongqing (little as in population: 34,000,000). I spent a day with the Zongers and, well, you know the rest. This is the email I sent to Steve Seidner, the CSC CEO and the guy who had the foresight to dispatch me to Chongqing. I was energized after my visit that day, and I wrote the email you see below that night. It was a dozen years ago. Hard to believe.

Oh, yeah, as you’re reading this…please click on the popup ads. The folks who put them up there pay us every time you do.

17 Dec 2011

Steve:

Just got back from the Zongshen meetings in Chongqing. This letter is a summary of how it went.

Our host and a driver picked us up in a Mercedes mini-van in the morning at the hotel. It was about a 1-hour drive to the Zongshen campus. Chongqing is a massive and scenic city (it just seems to go on forever). Imagine mid-town Manhattan massively larger with taller and more modern buildings, built in a lush green mountain range, and you’ll have an idea of what the city is like. We took a circular freeway at the edge of town, and the views were beyond stunning. It was an overcast day, and every time we came around a mountain we had another view of the city in the mist. It was like something in a dream. Chongqing is the Chinese name for the city. We in the US used to call it Chun King (like the noodle company). We drove for an hour on a freeway (at about 60 mph the whole time) to get to the Zongshen campus, and we were still in the city. I’ve never seen anything like it. The city is awesome. I could spend 6 months here just photographing the place.

The Zongshen facilities are huge and completely modern. The enterprise is on a landscaped campus (all fenced off from the public) in the city’s downtown area. We were ushered into their office building complex, which is about as modern and clean as anything I have ever seen. You can probably tell from this email that I was impressed.

Let me emphasize this again: The Zongshen campus is huge. My guess is that they have something in excess of 1.5 million square feet of manufacturing space.

Here are some shots of some of their buildings from the outside…they have several buildings like this. These first two show one of their machining facilities.

There were several buildings like the ones above on the Zongshen campus. It was overwhelming. This is a big company. The people who work there live on the Zongshen campus (Zongshen provides apartments for these folks). They work a 5-day, 8-hour-per-day week. It looked like a pretty nice life. Zongshen employs about 2,000 people.

Here’s a shot showing a portion of the Zongshen office building. Very modern, and very nicely decorated inside.

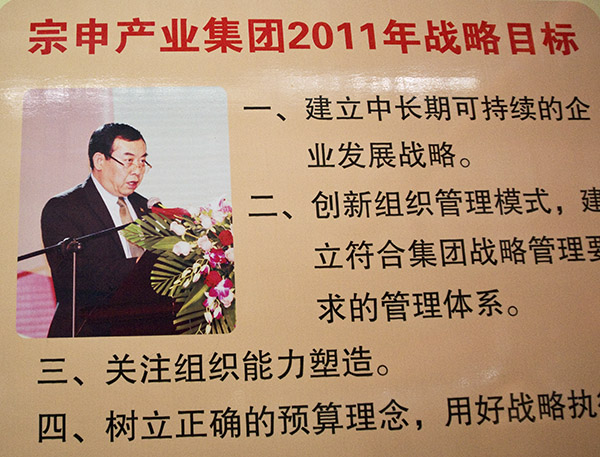

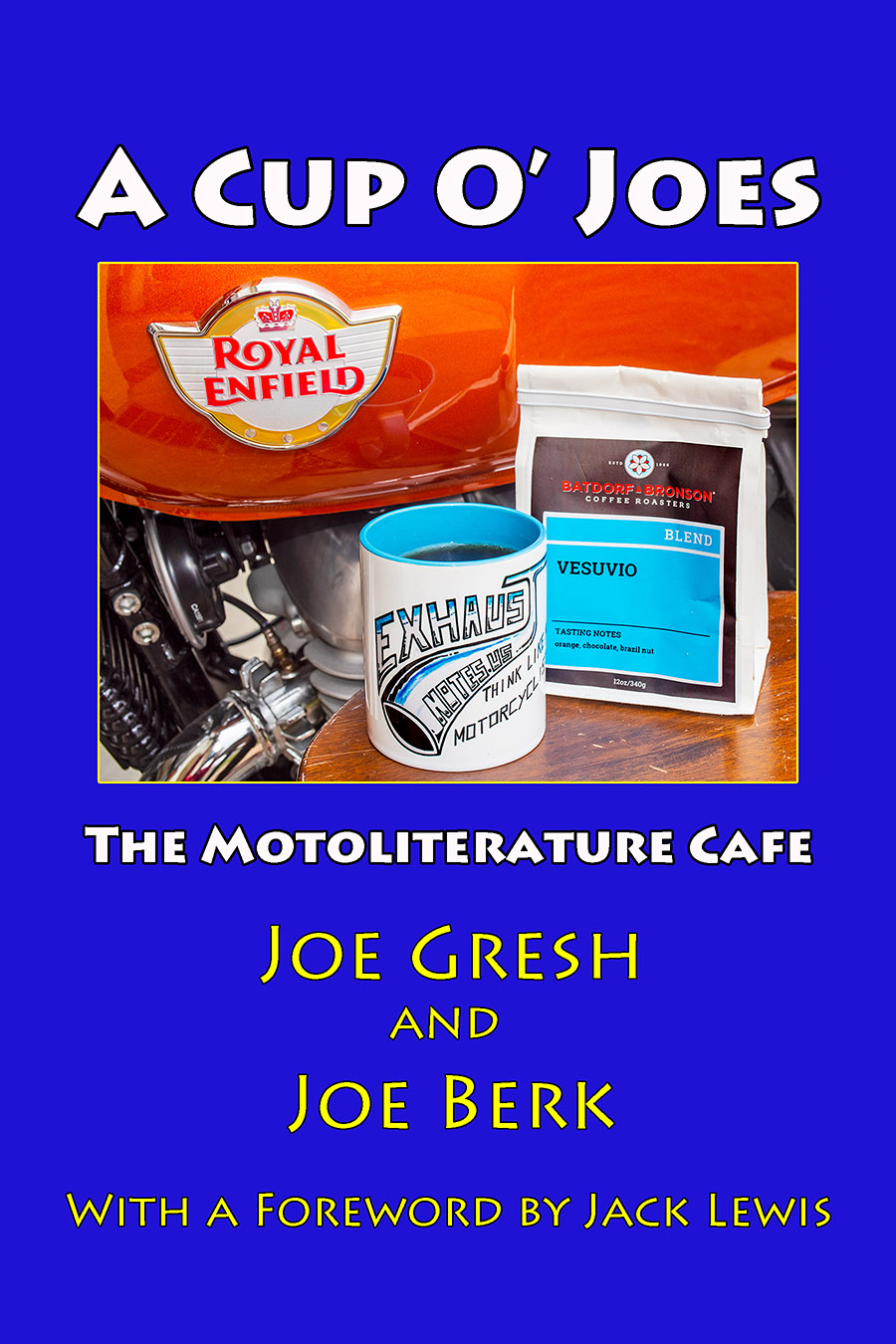

Zongshen is the name of the man who started the business. The company is about 20 years old. Mr. Zongshen is still actively engaged running the business (notice that he is not wearing a beret). I had the Chinese characters translated and what he is saying is “I want Joe to write our blog.”

Zongshen has a few motorcycles and scooters that have received EC (European Community) certification. They do not have any motorcycles that have received US EPA or CARB certification. They do have scooters, though, approved in the US. They have two models that have EPA and CARB certification. I explained that we might be interested in these as possible powerplants for future CSC motorcycles.

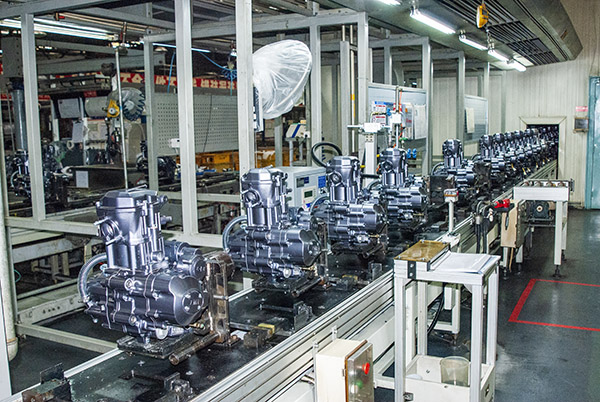

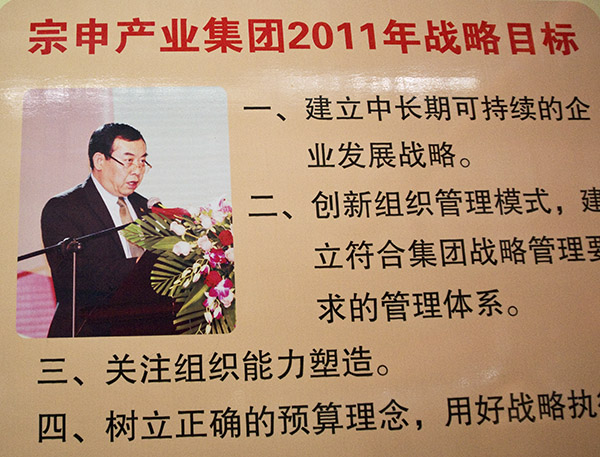

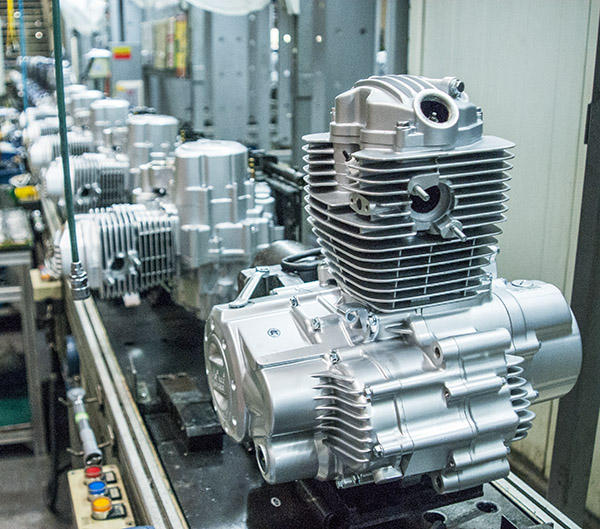

I asked to see the factory, and they took us on a factory tour. In a word, their production operation is awesome. The next several photographs show the inside of their engine assembly building (they had several buildings this size; these photos show the inside of just one). It was modern, clean, and the assembly work appears to be both automated and manual (depending on the operation). Note that we were in the factory on a Saturday, so no work was occurring. I was thinking the entire time what fun it must be to run this kind of a facility. Take a look.

Zongshen has onsite die casting capabilities, so they can make covers with a CSC logo if we want them to. Having this capability onsite is a good thing; most US manufacturers subcontract their die casting work and I can tell you that in the factories I have managed, getting these parts on time in a condition where they meet the drawing requirements was always a problem in the US. Doing this work in house like Zongshen is doing is a strong plus. They have direct control over a critical part of the process.

In addition to all the motorcycle work, Zongshen makes power equipment (like Honda does). I grabbed this shot as we were driving by their power equipment factory.

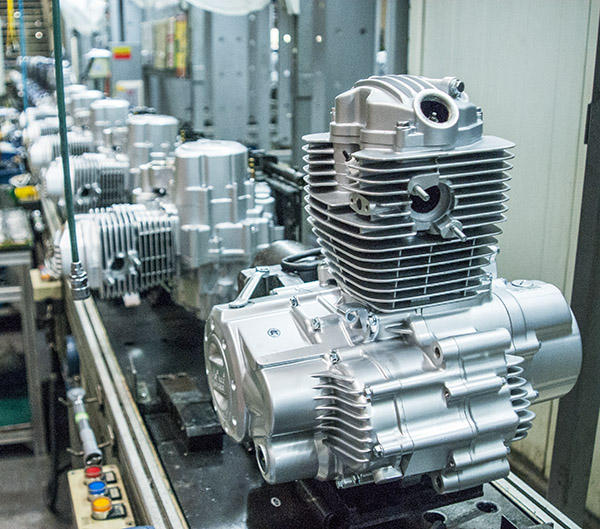

Here are some photographs of engines in work. Zongshen makes something north of 4,000 engines every day.

Yep, 4,000+ engines. Every day.

The engines above are going into their automated engine test room. They had about 100 automated test stations in there.

Zongshen makes engines for their own motorcycles as well as for other manufacturers. They make parts for many other motorcycle manufacturers, including Harley. They make complete scooters for several manufacturers, including Vespa.

These are 500cc, water-cooled Zongshen ATV engines….

Zongshen can make engines in nearly any color a manufacturer wants. When we walked by this display I asked what it was, and they told me it showed the different colors they could powder coat an engine.

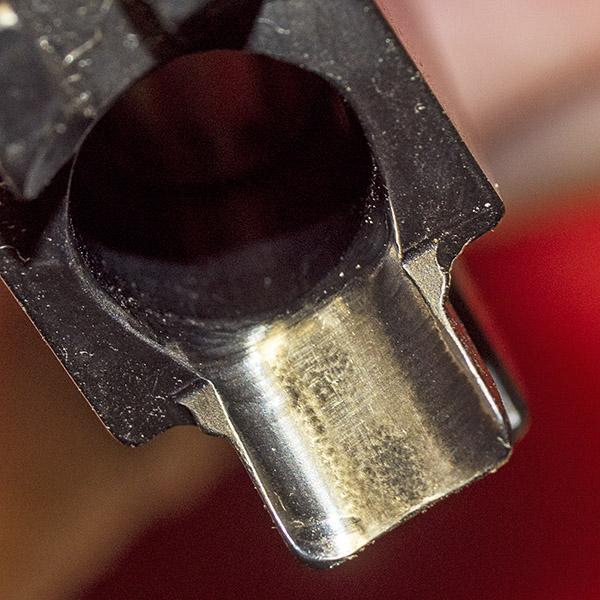

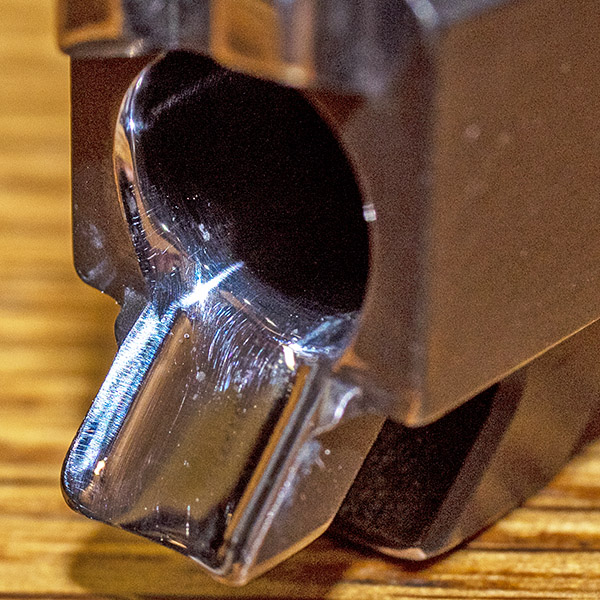

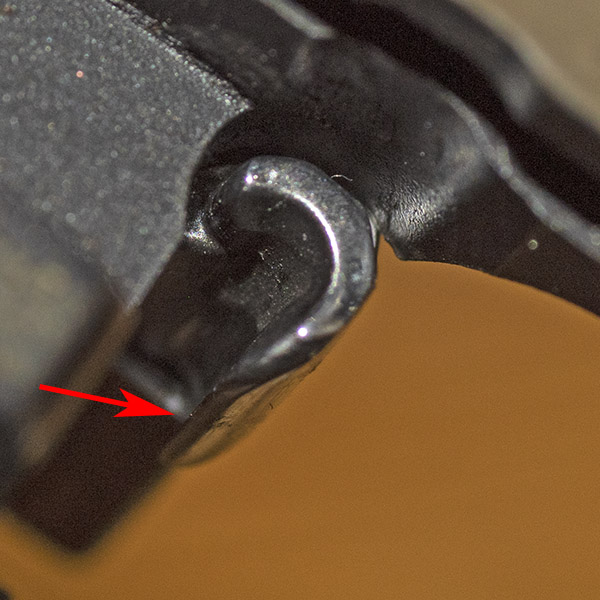

Quality appears to be very, very high. They have the right visual metrics in place to monitor production status and to identify quality standards. The photo below shows one set of their visual standards. These are the defects to avoid in just one area of the operation.

This idea of using visual standards is a good one. I don’t see it very often in factories in the US. It’s a sign of an advanced manufacturing operation. And here’s one set of their production status boards and assembly instructions…boards like this were everywhere.

The photo below shows their engine shipping area.

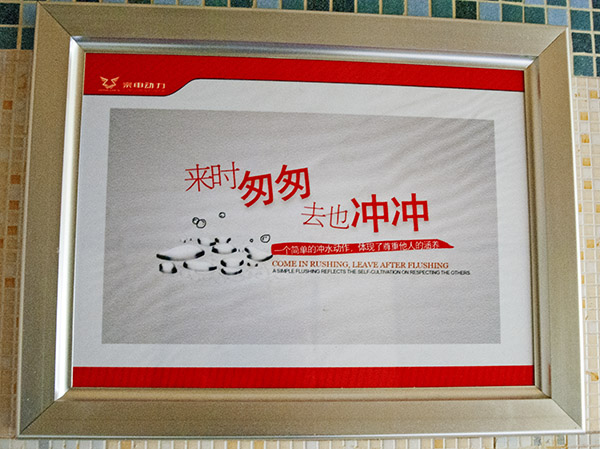

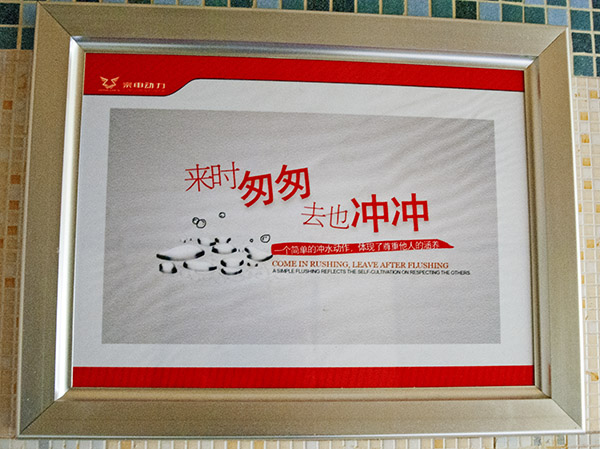

Here’s a humorous sign in the Zongshen men’s room…be happy in your work, don’t take too long, and don’t forget to flush.

As I said before, this entire operation was immaculate. Again, it’s a sign of a well-run and high quality plant.

We then briefly ducked into the machine shop. It was dark so I didn’t grab any photos. What I noticed is that they use statistical process control in manufacturing their machined parts, which is another sign of an advanced quality management approach.

I also have (but did not include here in this email) photos of their engine testing area. They test all engines (a 100% test program), and the test approach is automated. I was impressed. Zongshen’s quality will be as good or better than any engine made anywhere in the world, and we should have no reservations about using the 250cc engine in our CSC motorcycles. These guys have it wired.

My host then took us next to a factory showroom at the edge of the Zongshen campus. Here are a few photos from that area.

Check this one out…it’s a 125, and it looked to me to be a really nice bike.

Now check out the price on the above motorcycle. This is the all inclusive, “out-the-door-in-Chongqing,” includes-all-fees price.

Yep, that’s 8980 RMB (or Yuan), and that converts to (get this) a whopping $1470 US dollars. I want one.

The Chinese postal service uses Zongshen motorcycles….as do Chinese Police departments, and a lot of restaurants and other commercial interests. These green bikes are for the Chinese Post Office, and the red ones are for commercial delivery services.

Another shot from their showroom.

Zongshen also has a GP racing program, and they had their GP bikes on display with photos in the factory and the actual bikes in an office display area. Cool.

And finally one last photo, Steve, of Indiana Jones having a blast in Chongqing.

The bottom line, Boss, is that I recommend buying the 250 engine from these folks. Their factory is awesome and they know what they are doing. I write books about this stuff and I can tell you that this plant is as well managed as any I have ever seen.

I’ll be in the air headed home in a few more days. This trip has been a good one.

That’s it for now. I will send an email to the Zongshen team later today confirming what we want from them and I will keep you posted on any developments. Thank you for the opportunity to make this visit.

Joe

So there you have it. What followed was CSC becoming Zongshen’s North American importer, the RX3, the RX4, the TT 250, the San Gabriel line, the electric motorcycles, the Baja RX3 runs, the Andes Mountains adventure ride, the 5000-mile Western America Adventure Ride, the ride across China, the Destinations Deal ride, and more. Lots more. The first big ride with Zongshen was the Western America Adventure Ride, and in a few more days, we’ll post the story about how that came about. We were excited about hooking up with Zongshen; the Chinese were excited about riding through the American West. And ever since then, it has been one hell of a ride.

Stay tuned.

Never miss an ExNotes blog:

The latest from Dos Joes…buy your copy now!