I’ve been watching these cheap, cheerful, Chinese 7-inch headlamps sold through Amazon for quite a while. There are about twenty different sellers selling twenty different brand names of the same basic headlight. Normally priced around 25 to 30 dollars, this Qiilu brand light popped up on sale for 8 dollars and there was a coupon you could apply to the sale at checkout. It was a crazy good deal. When all was said and done Qiilu paid me 35 cents to receive their headlight. Ok, it wasn’t that good of a deal, but the light was like 7 dollars with shipping included.

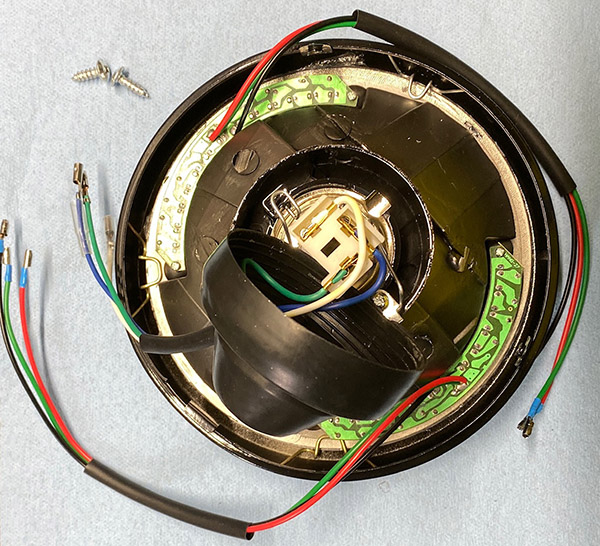

This headlight, like all of them on Amazon, comes with LED turn indicators or daytime running lights built into the outer edges of the lens. The entire LED cluster is removable but I plan on leaving them in and not connecting the wires. By the way, the light came with no wiring instruction so it’s kind of hit or miss. I only need the 3-wire main H-4 bulb for my project.

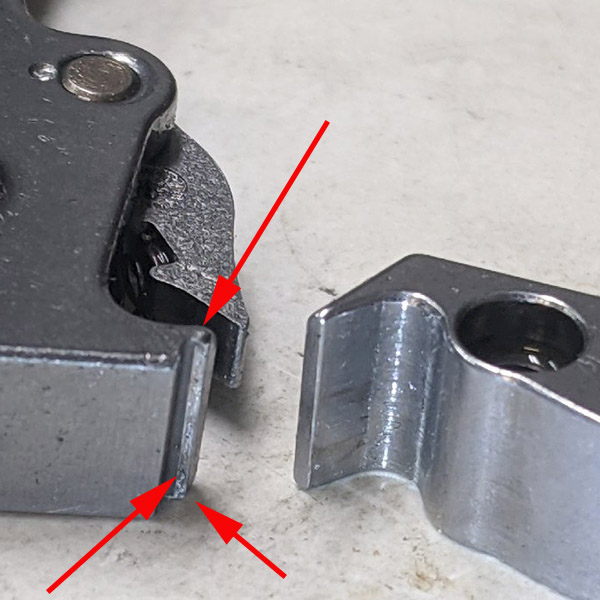

“What project is that?” You may well ask and I’ll tell you. The 2008 Husqvarna SMR 510 comes stock with the worst headlight ever installed on a motorcycle. It’s a 35w/35w incandescent type that has a strange socket more like a taillight bulb than a headlight. Replacement bulbs are easy to get online but impossible to find at any auto or motorcycle shop. And you’ll need to order a lot of them online as the stock bulbs only last about 250 miles before falling to pieces. The plastic reflector housing is slowly melting under the 35-watt bulb so increasing the wattage is out of the question.

I don’t know what went wrong with the reflector design but the Husky casts a gloomy glow not more than 30 feet ahead. Many a night I would ride home at 25 miles per hour, even then outrunning my lighting. As a stopgap I bolted on a large LED spotlight for off road use and it lights up things pretty well but is totally illegal for highway use as it blinds oncoming drivers the way I have it adjusted.

Enter the Qiilu. I’m removing the Husky headlight complete and replacing it with the Qiilu. The Qiilu uses standard bulbs found in any auto store so even if the bulbs continue to blow out I can re-light the sucker just about at will. The Qiilu reflector is twice as large as the stock Husky unit and uses a halogen bulb so I’m hoping for improved light pattern and strength.

But enough about my problems and me: How much headlight do you get for 8 dollars anyway?

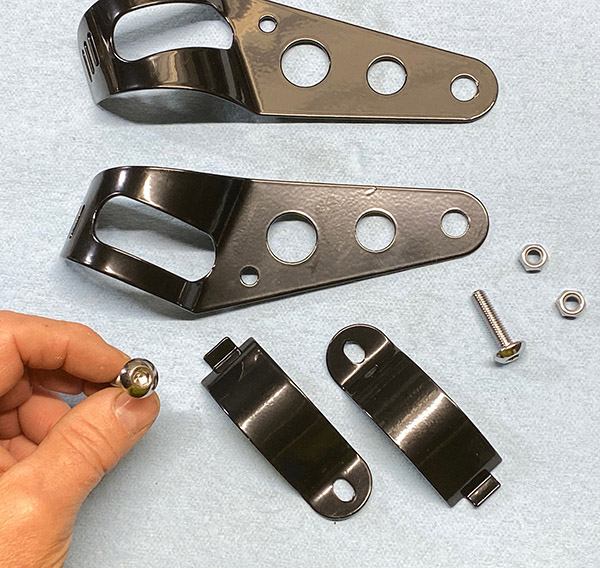

Turns out quite a bit. The Qiilu is mostly plastic except for the metal trim ring. The thing weighs nothing. The reflector and lens looks pretty nice. The light came with some universal mounting brackets and stainless steel, button-head fasteners that are worth 8 bucks all by themselves. I probably won’t use the brackets as I plan on fabricating a couple ears and re-using the Husky’s rubber band style headlight mounts. Any vibration I can muffle might make the bulbs last longer.

The Qiilu comes standard with a 35-watt bulb that is supposed to be yellow colored. I don’t see it but maybe a night it would. I’ll replace the bulb with a white 35-watt halogen that will cost more than the entire headlight.

The housing has a large opening in the back and I hope to stuff a lot of the loose, exposed wiring behind the stock headlight into the new housing. I may change the sheet-metal screws holding the rim to the housing to machine screws for a more secure attachment.

Look, this isn’t a super high quality lamp, but then I’m not a high quality person. It’s cheaply made but seems to have all the right parts in all the right places. The housing is not metal so will probably break if you hit a tree. The thing is, the Husqvarna headlight the Qiilu is replacing is even worse. I expect a rock hitting the Qiilu square in the lens will crack the thing but maybe not. For 8 dollars it’s worth a try and beats the heck out of no light at all.

More ExhaustNotes product reviews are here!

I met Charlie Wilson a couple of times when I was an engineer in the munitions business, so

I met Charlie Wilson a couple of times when I was an engineer in the munitions business, so