There’s a Facebook group called Snub Noir and I enjoy it. They have a lot of good info there about concealable revolvers, and it projects kind of a ’40s/’50s/’60s vibe having to do with private investigators and police officers (and movies, TV shows, and novels from that era). It’s centered on the Colt and Smith snubbies of the day, and on today’s snubbies, too. If you’re into snub nosed revolvers, you’ll like this place. If you visit it, you’ll understand the Gats and Hats thing.

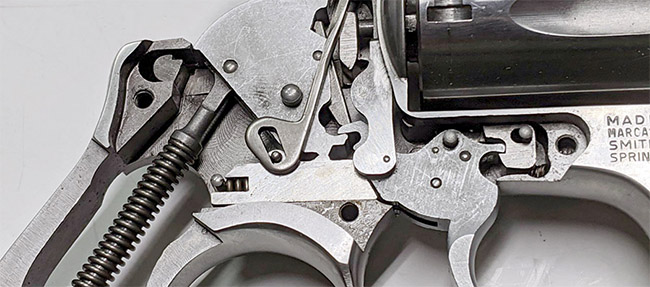

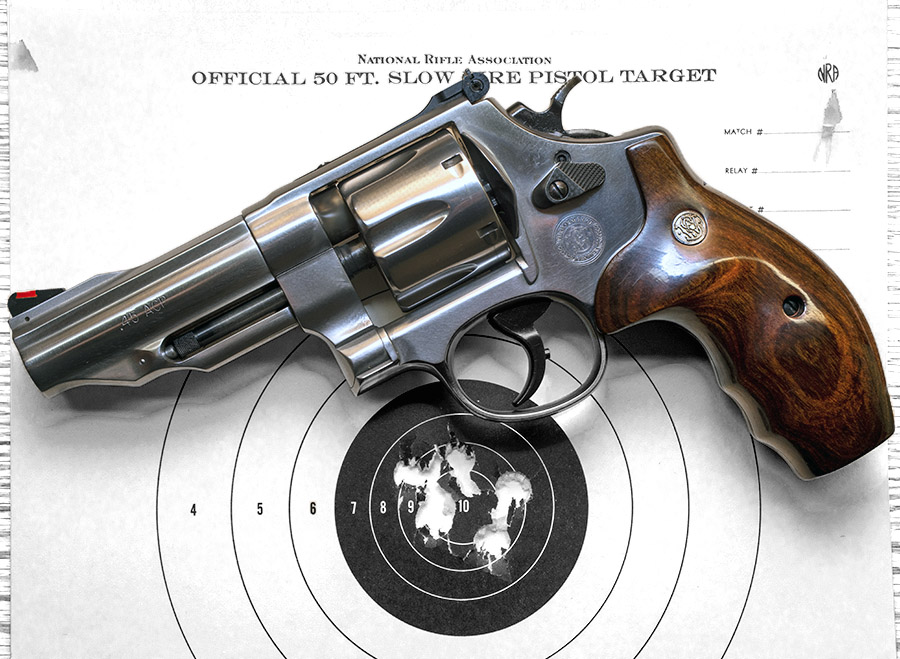

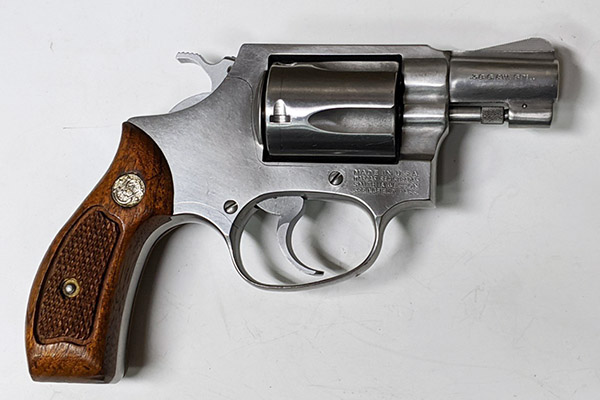

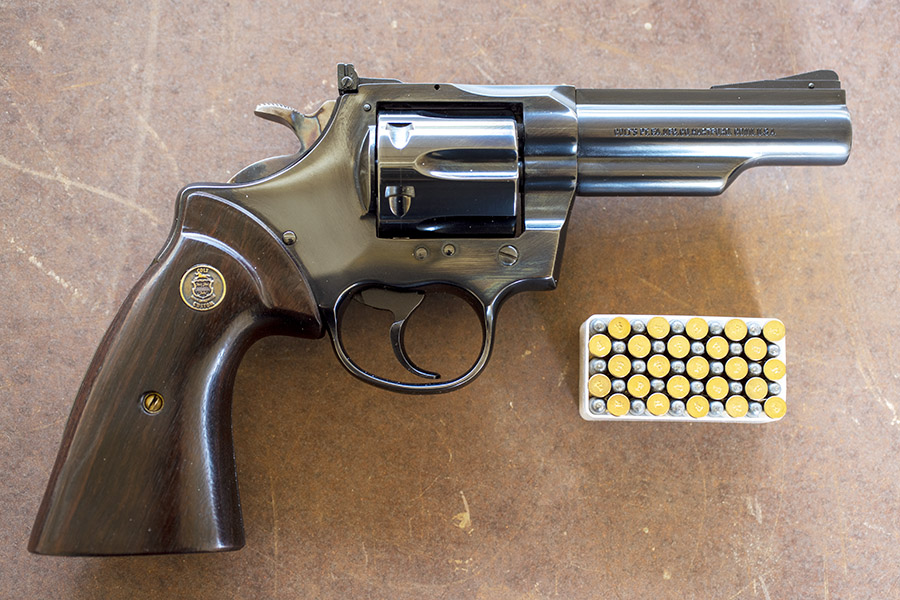

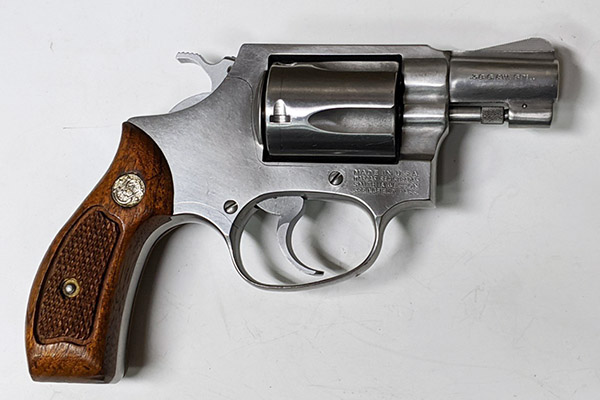

That beautiful S&W Model 60 you see in the big photo above is my personal carry gun and it’s a sweet piece. It’s been selectively polished, it has Altamont grips, and it has a TJ action job (you can read more about TJ’s work on his website and I’ll give you a few more links on my Model 60 at the end of this blog). I’ve done a fair amount of load testing with the Model 60 and I know the loads it likes from accuracy and shoot-to-point-of-aim perspectives. The best load is the FBI load, which is a 158-grain bullet over 3.5 grains of Winchester 231 propellant.

I wanted to try something different, though. I’ve shot the Model 60 at 50 feet, 25 yards, 50 yards, and 100 yards. I know, I know: Those latter two distances are not really what the snub nose revolver designers had in mind when they designed these guns. But I was curious when I did those tests. I know a retired police officer who can hit a clay target at 50 yards (the kind you dust in trap or skeet shooting).

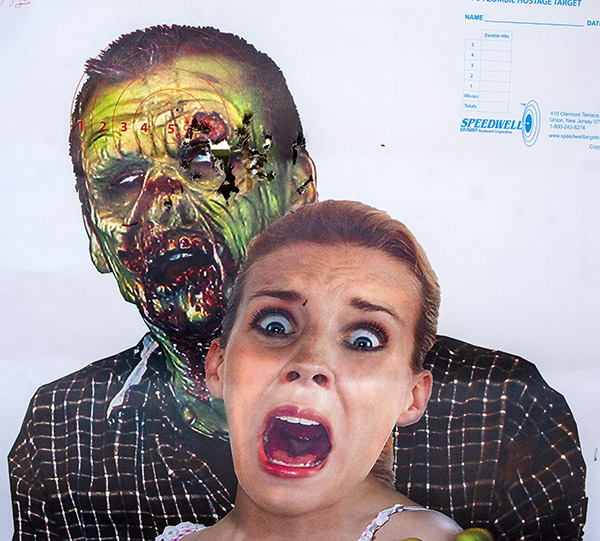

The police sometimes qualify at 7 yards, and I think that’s more in line with what a snubbie is intended to do. And, you know, there’s this zombie apocalypse thing that’s coming down the road. I’ve done my homework, and I know that most zombie hostage incidents (i.e., where a zombie is holding a damsel in distress) occur at 7 yards. I wondered: How would I do firing my Gat double-action as quickly as I could at 7 yards? I want to be prepared, you know.

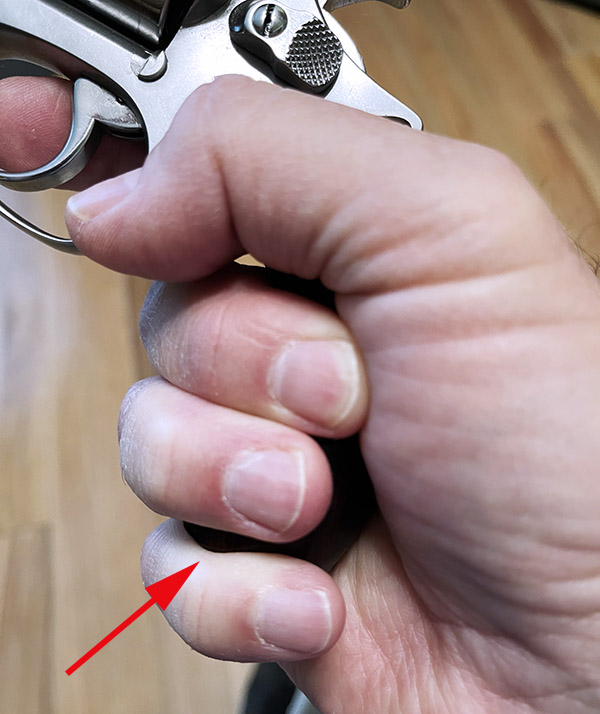

Fortunately for me, zombie-holding-hostages targets are readily available on Amazon, so I grabbed a couple and headed to the range to test my hostage rescue skills with two different loads. The first was the old bullseye target competition .38 Special standard: A 148-grain wadcutter (in this case, copper-plated wadcutters from Xtreme Bullets) over 2.7 grains of Bullseye propellant. It’s the load I’m set up to produce in large quantities on my Star reloader, and it’s the load you see in the top photo (the Dr. Seussian Gat in the Hat pic). The other is the FBI load mentioned above: A 158-grain bullet and 3.5 grains of Winchester 231 secret sauce.

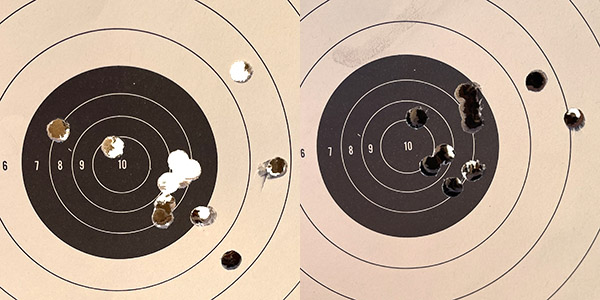

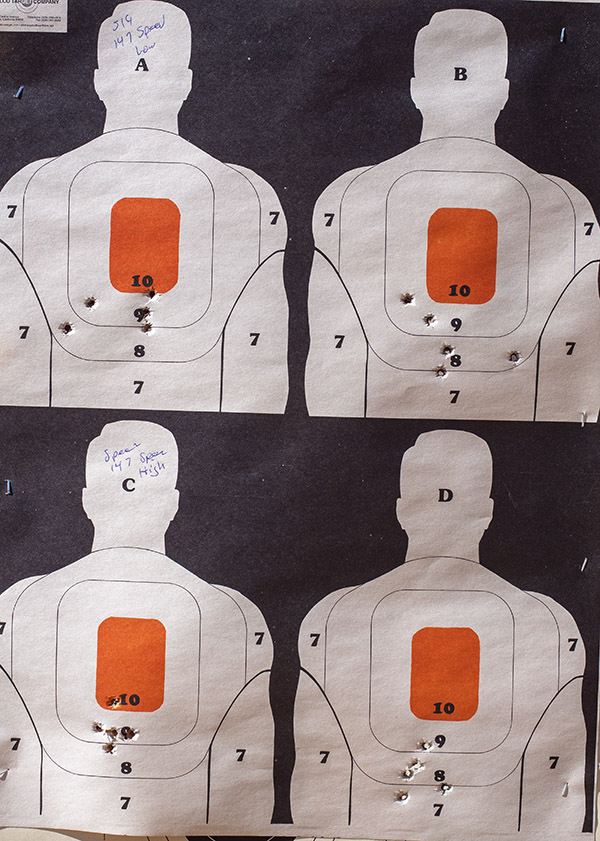

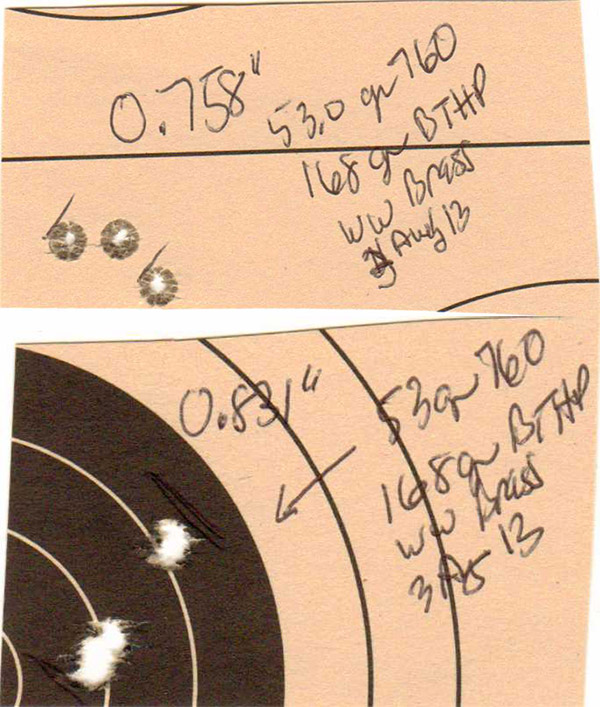

So how’d I’d do? The short answer is not too bad. Not as good as I thought I would, but good enough and certainly close enough for government zombie work. The first target (the one immediately below) shows the results of six full cylinders (30 rounds, as the Model 60 holds five rounds). The good news is 29 of those shots went directly into the zombie’s noggin and none hit Betty (the hostage).

The bad news? One of the wadcutter bullets tumbled. Fortunately for Betty it went right over her head. You can see the bullet’s outline in the target above. It might have been that the Star threw a light load on that round, or maybe a case split and let too much pressure escape, or maybe these light target loads are marginal in the Model 60’s short 2-inch barrel. Win some, lose some. Betty’s okay, though…that’s the important thing.

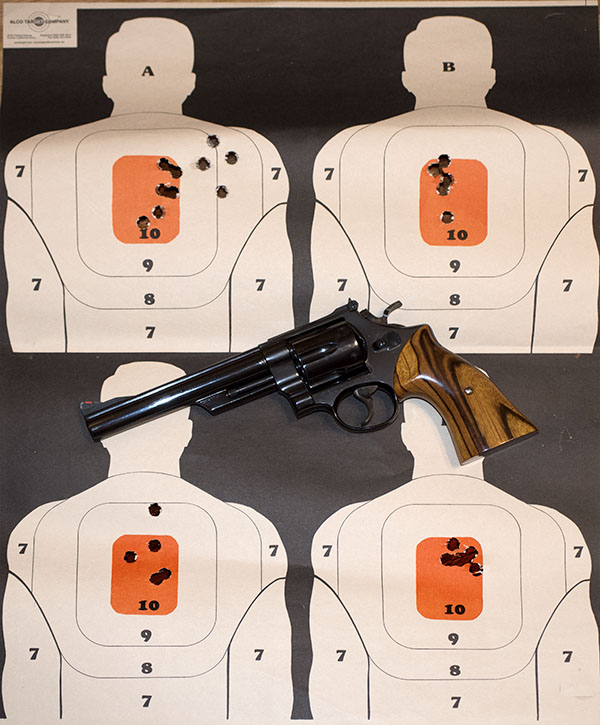

Not surprisingly, the FBI load did much better (old J. Edgar know what he was doing against both zombies and commies, I think). The 30 holes you see in Mr. Zombie below went into a tighter group, none of the bullets tumbled, and most importantly, none of them went into Betty.

I feel better now. I know if I can keep my wits about me and I have my Model 60, and if I can get the zombie to pose with Betty like you see above at 7 yards, he’s toast and Betty’s going to be just fine. For any zombies who follow the ExNotes blog: You’ve been warned.

Never miss an ExNotes blog…sign up for free:

As this blog’s title states, this blog is Gats and Hats I. Will there be a Gats and Hats II? Stay tuned, my friends. Two more days, and we’re calling in the heavy artillery.

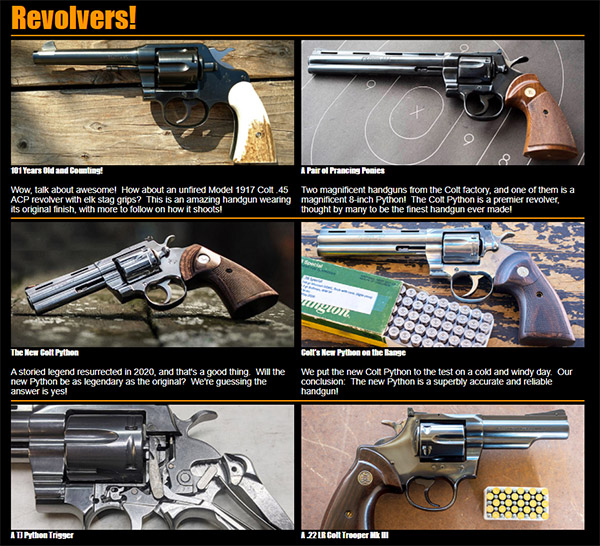

More gun stories? Hey, it’s what we live for!

Want to know more about the Model 60 featured in this blog? It’s all in the links below: