My Rock Island Armory Compact 1911 is a favorite. I carry with factory ammo (Winchester’s 230-grain hardball, like I had in the Army). But that’s not what I shoot on the range; there, I shoot reloads exclusively. This blog answers a question keeping all of us awake at night: Where do different loads shoot compared to factory ammunition?

What you’re going to see aren’t tiny target groups. The Rock Compact 1911 is a concealed carry handgun. I know Facebook trolls can shoot dime-sized 1911 groups at 100 yards with both eyes closed. What you see below are my groups.

I have three favorite loads for my .45. The first is one I’ve been shooting for 50 years. That is a 230-grain cast roundnose bullet (I like Missouri bullets, although I’ve had good luck with just about any cast 230-grain roundnose), 5.6 grains of Unique, whatever primers I can find, and whatever brass I have on hand. I use the Lee .45 ACP factory crimp die on all my ammo; overall length is 1.262 inches. This load is a bit lighter than factory ammo, but not by much. The good news is it feeds in any 1911 (it doesn’t need a polished ramp and chamber) and wow, it’s accurate.

The next load is a 200-grain cast semi-wadcutter bullet (I use Missouri or Speer), 4.2 grains of Bullseye, anybody’s primers, and mixed brass. Cartridge overall length on this one is 1. 255 inches. The semi-wadcutter profile usually needs a polished feed ramp and chamber.

The third load is a 185-grain cast semi-wadcutter bullet and 4.6 grains of Bullseye. For this test, I had CCI 350 primers. My usual 185-grain cast load uses 5.0 grains of Bullseye and a CCI 300 primer, but primers are tough to find these days so I dropped the powder down to 4.6 grains. Lately I’ve been using Gardner powder-coated bullets. They look cool and they’re accurate. Cartridge overall length is 1.260 inches. Like the load above, this one needs a polished ramp and chamber, too.

And then there’s factory ammo. I use 230-grain hardball from Winchester. Just for grins I measured its overall length; it is 1.262 inches. Factory hardball typically runs between 1.260 and 1.270 inches.

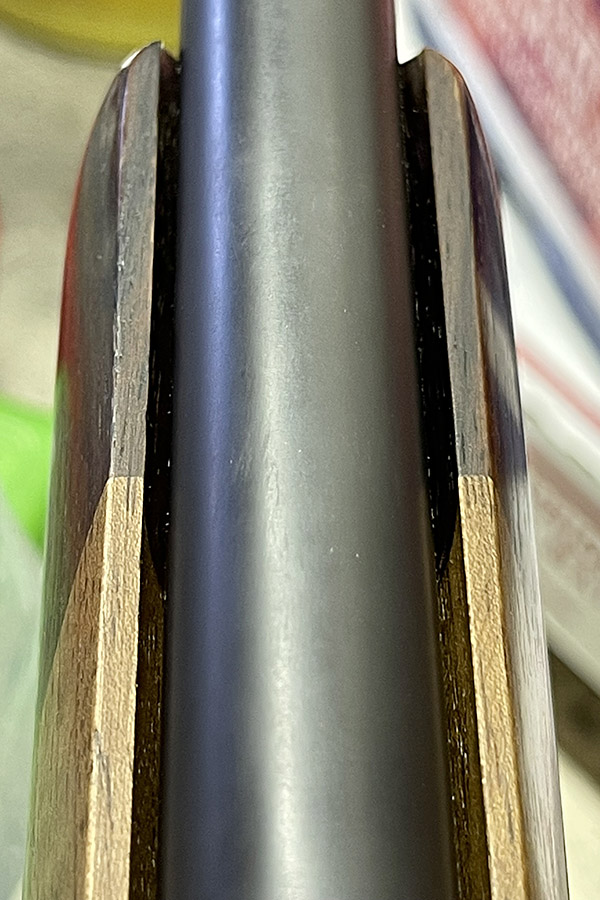

Good buddy TJ over at TJ’s Custom Gunworks polished my Compact’s ramp and chamber (it feeds anything), he recut the ejector (no more stovepiping) and fitted a better extractor, he polished the barrel and the guide rod, he engine-turned the chamber exterior, and he installed red ramp/white outline Millett sights. The Compact didn’t need a trigger job; it was super-crisp from the factory. I added the Pachmayr grips. You can read more about the Rock here.

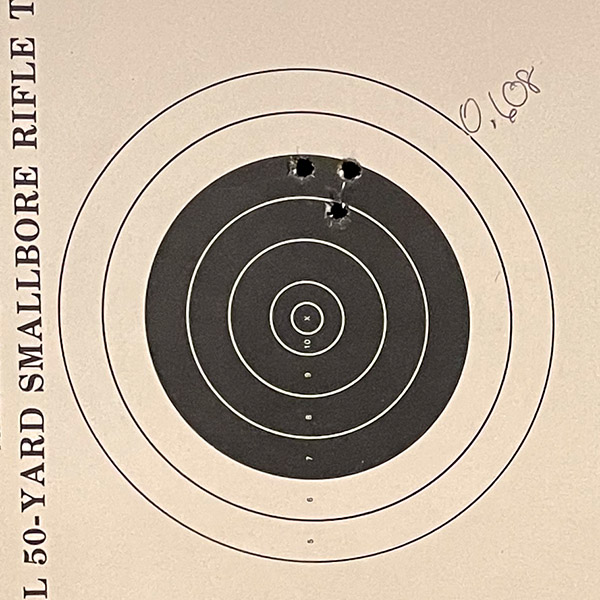

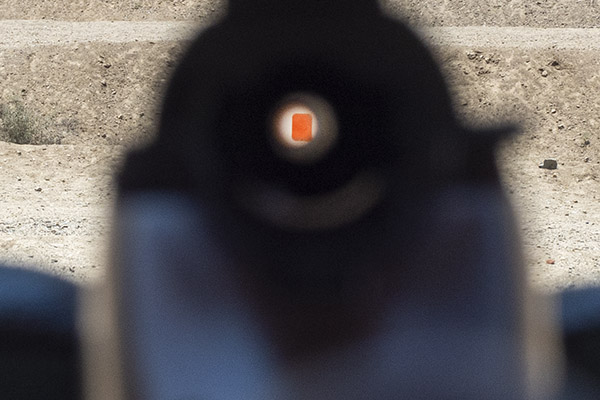

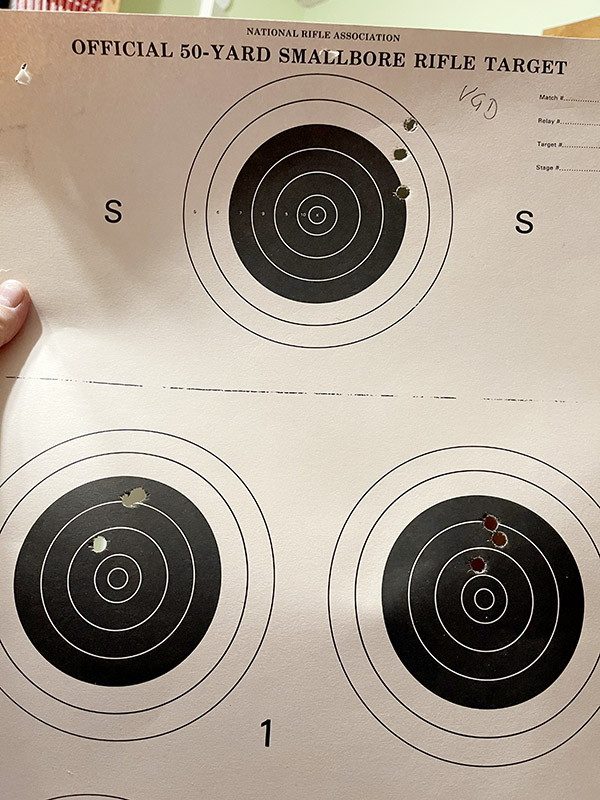

All shooting was at 50 feet, all groups (except with factory ammo) were 5-shot groups, I used a two-hand hold, and my point of aim was 6:00 on the bullseye.

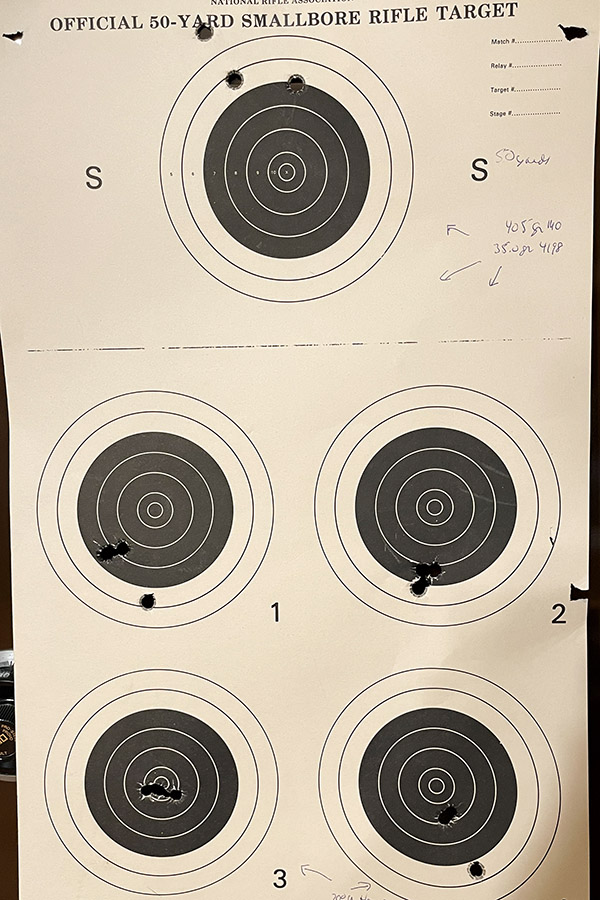

I shot my first set of four groups with the 185-grain cast semi-wadcutter load. As you can see on the target below, the groups move around a bit. That notwithstanding, the center of the groups seems to be pretty much right on the point of aim.

About that 4.6 grains of Bullseye with the CCI magnum primers: The standard load (5.0 grains of Bullseye and regular primers) is a much more accurate load.

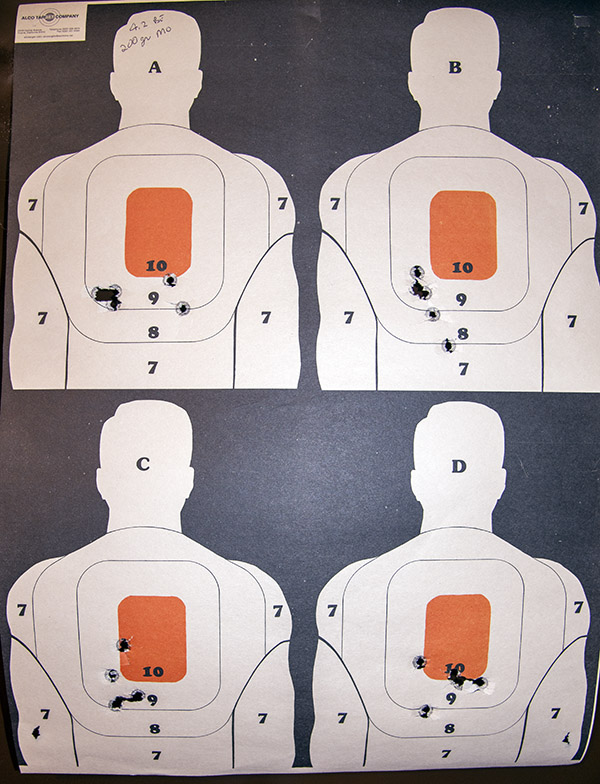

The next four groups were with the 200-grain cast semi-wadcutter. The center of these groups is maybe just below the point of aim. Maybe. It’s very close to the point of aim.

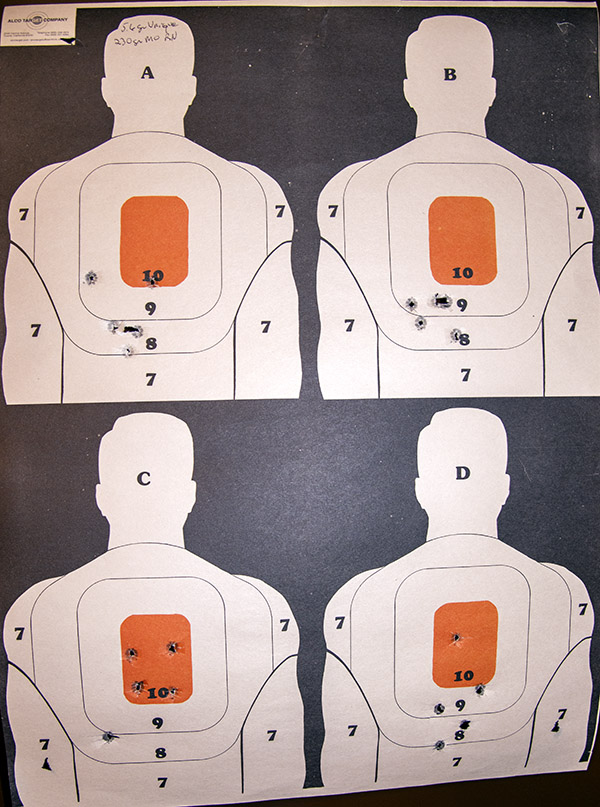

Next up was the 230-grain cast roundnose load. The groups are about 2 inches below the point of aim and maybe slighly biased to the left, but they’re still pretty close.

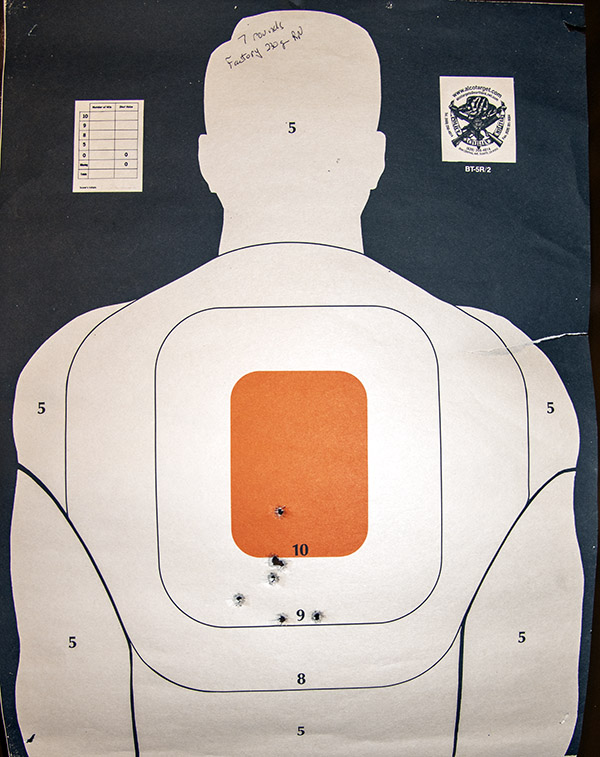

My last shots were with the Winchester 230-grain roundnose factory ammo. I used a full-sized silhouette target (not the four-targets-per-sheet targets you see above) and again, I held at 6:00. The point of impact is just about at point of aim (maybe a scosh lower).

The bottom line? The Compact shoots different loads to different points of impact, but the difference isn’t significant. Predictably, the 230-grain loads shoot a little lower than the 200-grain loads, and the 200-grain loads are a bit lower than the 185-grain loads. Factory ammo shoots essentially to point of aim. The differences wouldn’t matter on a real target. For a fixed sight combat handgun all are close enough for government work.

One last comment: Every load tested fed and functioned perfectly with my TJ-modified Compact Rock. If you want world class custom gun work, TJ’s Custom Gunworks is the best.

What’s next? I’m going to repeat this test, but with a Turnbull-finished Smith and Wesson 1917 revolver. That’s going to be fun.

More Tales of the Gun!

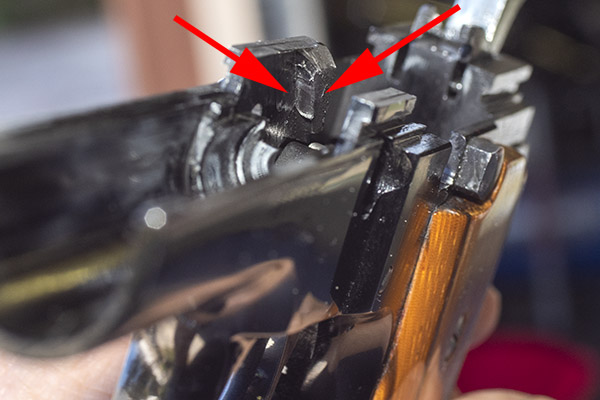

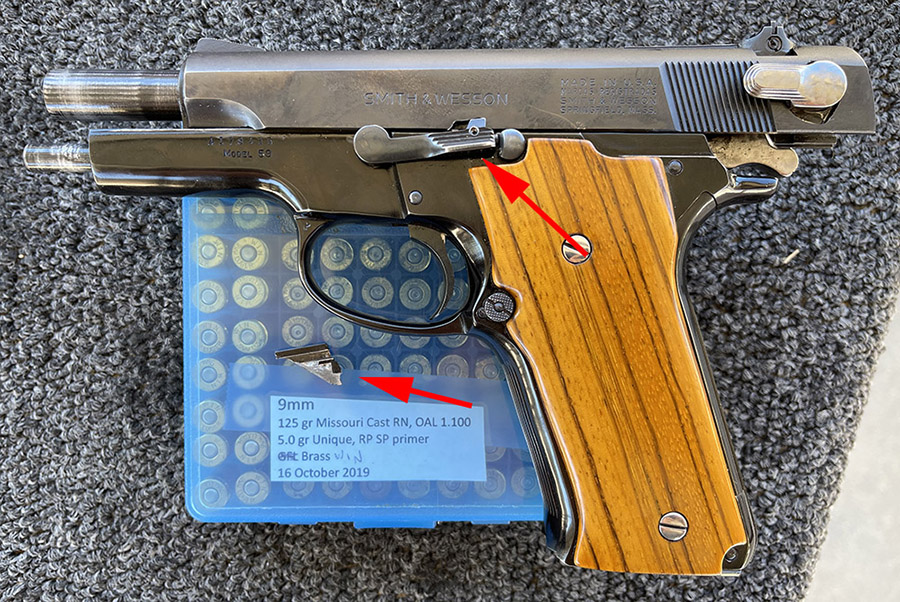

The arrows in the next pic point to the matching right side of the Model 59 frame. Note the worn area. It’s where the barrel ramp contacts the frame ramp when the gun recoils. That ramp (along with the mating ramp on the barrel) drops the barrel slightly to disengage it from the slide when the slide moves to the rear. You can see this area took a beating over the last 50 years. The photo shows the opposite side of the frame, where it didn’t break.

The arrows in the next pic point to the matching right side of the Model 59 frame. Note the worn area. It’s where the barrel ramp contacts the frame ramp when the gun recoils. That ramp (along with the mating ramp on the barrel) drops the barrel slightly to disengage it from the slide when the slide moves to the rear. You can see this area took a beating over the last 50 years. The photo shows the opposite side of the frame, where it didn’t break.