By Joe Cota

This is my tale about restoring a very ugly and broken vintage 1968 Ruger Blackhawk that had the safety conversion done by the Ruger factory. I think Skeeter Skelton would have approved! (Skeeter Skelton was an American lawman and prolific gunwriter well known to firearm enthusiasts.)

First, a little background on the single action revolver, or “sixgun” as they are called. In 1872 the US government was looking for a new service revolver to replace its older Colt and Remington cap-and-ball revolvers used in the Civil War. Colt developed a sixgun that utilized the then new technology metallic cartridge. Colt was the successful contractor and their cartridge gun was adopted by the government in 1873 as the 1873 Colt Single Action Army. The 1873 Colt SAA was shortly thereafter offered to the civilian market and became very popular with ranchers, lawmen, cowboys and bad guys alike. The “Peacemaker” (as Colt’s SAA became known) was priced around $15, which was most of a drover’s wages for a month.

After WWII a new-fangled gizmo called television started to become affordable. In 1948 about 1% of American households owned a television, and by 1955, 75% of American households owned at least one television set (black and white with “rabbit ears” antenna, of course). The TV set became the center of the living room, and the entire family would gather around the “set” after dinner. Hollywood’s golden age of TV westerns from the mid-1950’s through the 1960’s produced an astounding number of instant hits with shows like Have Gun Will Travel, Rawhide, Wanted Dead or Alive, and The Rifleman. All of them featured the Colt SAA and Winchester repeating rifles, or the “lever gun.” Every red-blooded American boy and his father and his uncles and even some moms wanted to own and shoot their very own Peacemaker. But there was a problem: The Colt sixguns were expensive and often not available.

That’s when Bill Ruger decided to give the public what they wanted. In 1953 Ruger introduced the Single Six revolver chambered in .22 Long Rifle. It was a sixgun for every boy! Two years later in 1955 Ruger introduced its Blackhawk in .357 Magnum. This was a sixgun for every man! They were and still are wildly popular. About 700,000 of the pre-1973 Ruger Single Six .22 revolvers were made, and well over a million New Model Single Six .22 revolvers were made after 1973. I’ll defer the exact number manufactured to the Ruger historians.

Ruger’s Single Six and the original Blackhawk single action revolvers were patterned after Colt’s SAA. The Ruger has a similar shape, size, look and feel as the Colt on the outside. But on the inside Ruger made some improvements. Ruger’s guns used modern high-strength carbon steel. Colt’s action ran on leaf springs prone to breakage. Ruger replaced the brittle leaf springs with much tougher coil springs made from piano wire. The Ruger guns are much tougher than the Colt.

One of the infamous traits both Ruger’s initial guns and the Colts share is the first small hammer cock position called the “safety” is not safe. A gun with all six cylinders loaded, if accidently dropped, is prone to the safety failing (resulting in a negligent discharge). Therefore both the Colt and pre-1973 Rugers should only be carried with five rounds loaded and the hammer down over an empty chamber. These pre-1973 Ruger sixguns are known as the “three-screw” Rugers, as identified by the three plainly visible screws on the left side of the frame, just as the Colts have three screws. The original Rugers are also called Old Models, for reasons that become clear in a minute.

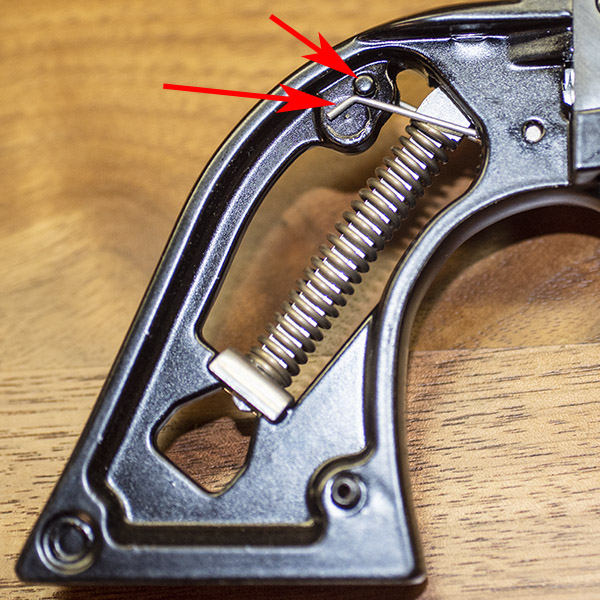

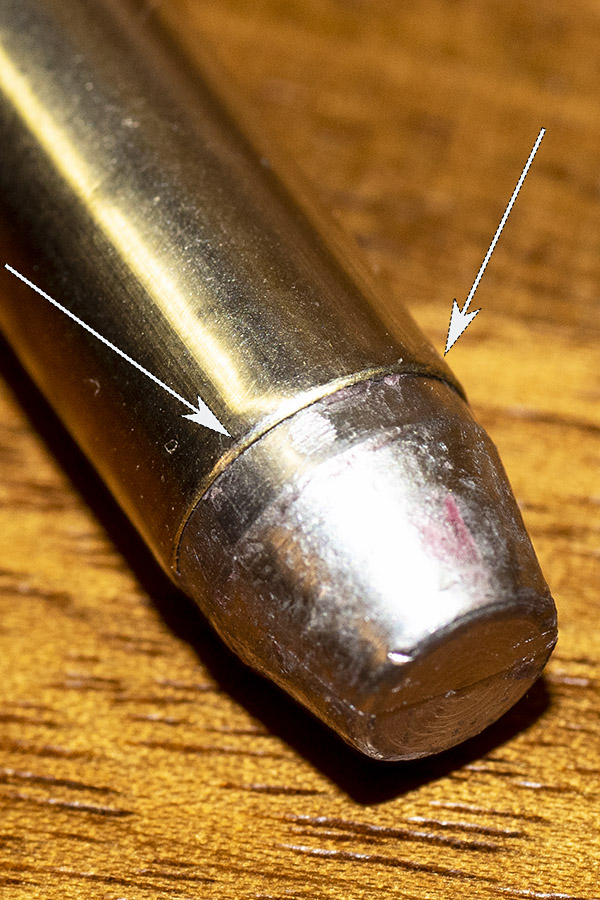

As the story goes, someone who didn’t follow what is clearly stated in Ruger’s owner manual to carry only with the hammer over an empty chamber, dropped their Old Model Ruger, fully loaded with six rounds, and shot himself in the leg. Apparently, there were other negligent discharges and expensive lawsuits. This prompted Ruger’s engineers to develop a safer design Ruger sixgun. This newer design is called the New Model Blackhawk. New Model Rugers can safely be carried with all six chambers loaded. Beginning in 1973 all the New Model Rugers have what’s called the “transfer bar safety.” It basically works by making a mill cut in the front (or face) of the hammer so that in the down position the hammer face can’t possibly touch the frame-mounted firing pin. When cocked back in the shooting position, a steel bar (the transfer bar) attached to the trigger mechanism is raised. When the trigger is depressed, the transfer bar fills the gap between the milled cutout on the hammer face and the firing pin, effectively “transferring” the hammer’s impact to the firing pin.

The 1973 and later New Model Rugers are easily identified because they do not have the three screws. They have instead two pins. Another difference is that there is no “half cock” position for loading the gun. The cylinder freely rotates for loading simply by opening the loading gate. The New Model Rugers work well enough but do not have the distinctive feel and clicking sound while cocking the hammer as do the Colts and old three screw Rugers. The New Model trigger is not quite as smooth as the older designs because of increased drag and the friction of the transfer bar as it moves into position. Some shooters claim they don’t notice the differences between the two, but I own both and I can feel the difference.

In 1975, Ruger engineers devised a method of retrofitting all of the “unsafe” pre-1973 sixguns with a makeshift transfer bar. They ran a campaign in the gun periodicals that prompted owners to ship their old guns to Ruger and they would “upgrade” the older guns to make them safe to carry with all six chambers loaded.

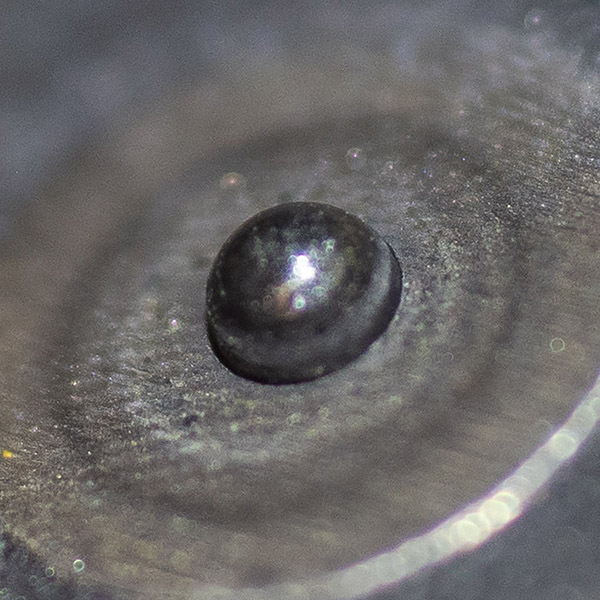

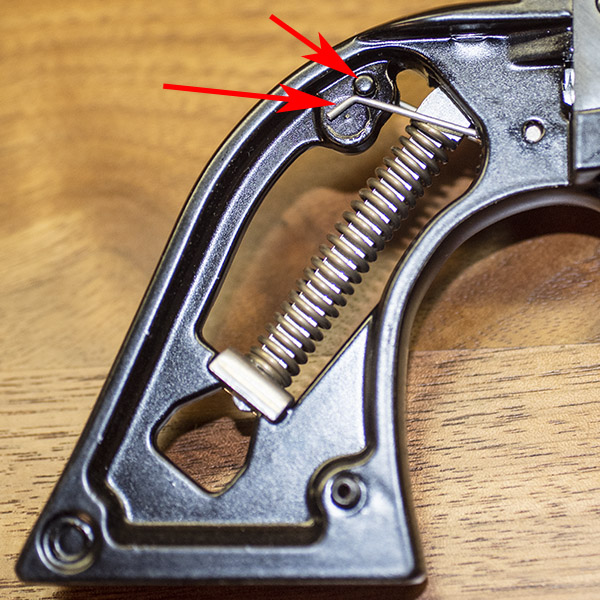

It remains unknown how many owners sent their guns back to Ruger, but apparently there were thousands because we see many of these retrofitted guns on the used gun market today. They are three screw guns that function similar to the New Model two pin guns, but unfortunately the trigger pull on the converted guns is absolutely terrible. The retrofit-style transfer bar scrapes up along the back side of the frame causing an awful, gritty, jerky feel. To make matters worse, the retrofit cylinder base pin is fitted with a small spring-loaded pin that also drags against the transfer bar to push it out and over the firing pin on its upward travel. If the retracting pin gets stuck, the transfer bar pushes into the firing pin, locking up the gun. The retrofitted three screw Rugers are pretty bad, taking all the smoothness from the action.

Ruger reportedly returned the retrofitted guns back to their owners with the original parts sealed a small plastic bag. Many of these plastic parts bags have been separated from the converted guns (they were either lost or thrown away). Ruger doesn’t offer any of these old parts for sale to the public, as they consider them unsafe. If an old unconverted three screw is sent in Ruger for any type of repair, they will return it to its owner with the transfer bar conversion installed, whether the owner asks for it or not. In fact, Ruger will not work on an unconverted old model gun without doing the conversion.

Unconverted three screw models (i.e., unaltered Old Model Rugers) today command premium prices among collectors. Even with the parts bag, the converted Old Models will never realize their true collector value because Ruger has permanently marked the converted guns with an “R” on the frame. The stamp is concealed underneath the grip frame to prove that the factory had done the conversion even if an owner wished to restore it back to its unaltered condition. Ruger will install the Old Model conversions but only if the owner sends the gun to them for installation, and Ruger will stamp the frame showing that they did the conversion.

Converted Old Model Rugers having the afterthought safety conversion are generally not very good shooters. However, restored back to original, these guns make very nice non-collectible shooters for those able to locate the original parts. The Old Model unconverted guns handle much better than the New Model guns, provided a most important safety rule is strictly adhered to. That rule is to never carry the restored-to-original Old Model Ruger with the hammer over a loaded cylinder. This brings us to the point of this story.

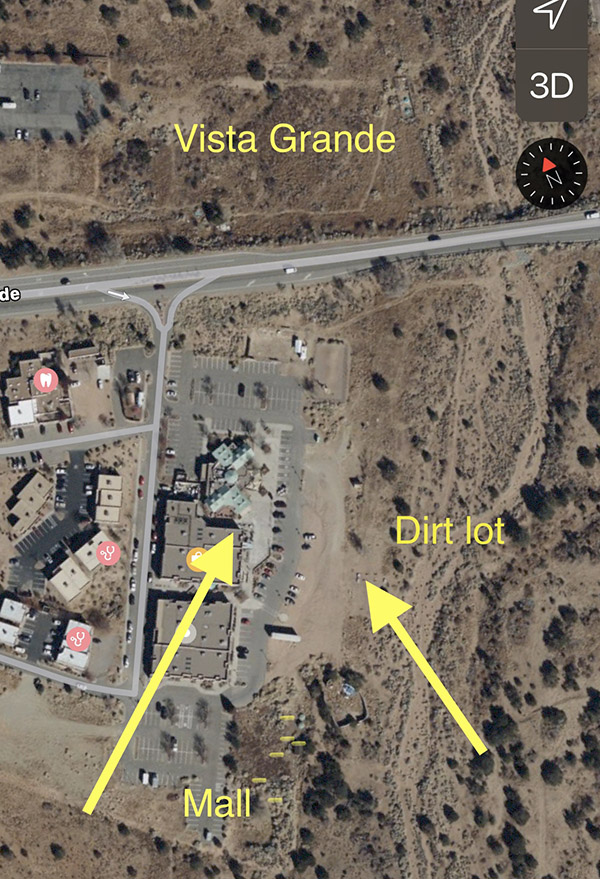

Six years ago I stumbled upon an Old Model 1968 three-screw Blackhawk being sold as a parts gun at the Ventura Crossroads gun show. The cylinder was totally locked up due to the transfer bar conversion (as described above). However, the asking price was so low that I won’t tell you the cost because you wouldn’t believe me. Besides being broken it had a ventilated rib that I had never seen before on any Blackhawk. It was truly an ugly duckling Ruger Old Model Blackhawk! But it had a great finish and the original factory grips, so I went for it without haggling over the price. Man, I’m not kidding. This gun’s price was so low it was almost free.

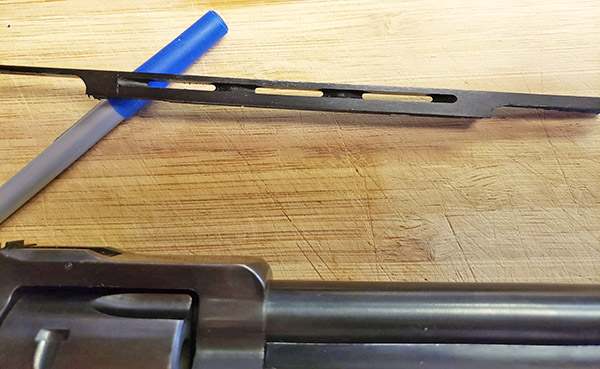

After the 10-day cooling off period, I brought the ugly little Old Model sixgun home, along with a brand-new, high-quality gunsmith screwdriver set. After disassembling the Ruger, I found that the cylinder was frozen because of the factory safety conversion. After cleaning it up and freeing the cylinder, the gun had the absolute worst sandy, gritty, heavy sticky trigger I’ve ever experienced. It now worked but it had a terrible action, and it was still the ugliest Blackhawk I had ever seen.

After more research I found that Ruger never made a Blackhawk with a ventilated rib. This gun had a phony aftermarket glued-on rib made by the Poly Choke company. I guess the owner wanted something that looked like a Colt Python and decided to dress up the Ruger for Halloween. I managed to pull the fake ventilated rib off without causing any damage to the barrel, but it wasn’t easy. The Poly Choke adhesive was pretty tough. After pulling the rib off, the remaining glue was removed using brake cleaner spray. By now the gun was looking pretty good again, but the action still sucked.

To smooth up the action, I removed the transfer bar conversion and replaced it with factory original parts to restore it to the original, classic “5-shooter” configuration. Unfortunately, the gun didn’t come with the old parts bag but I was determined to restore it. Now before any of the do-gooder Ralph Nader safety types out there proclaim “how irresponsible of you,” allow me to ask if you’ve ever seen an original Colt SAA with a safety conversion? Well, no, you have not because Colt had the good sense to not ruin their guns with an ill-designed stopgap transfer bar safety.

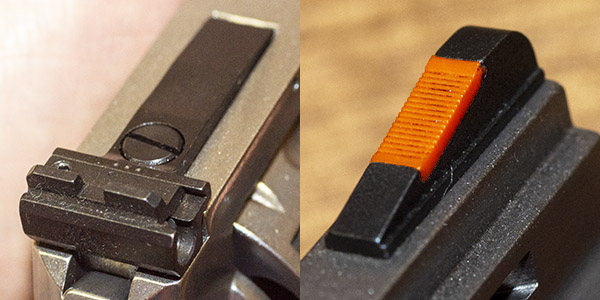

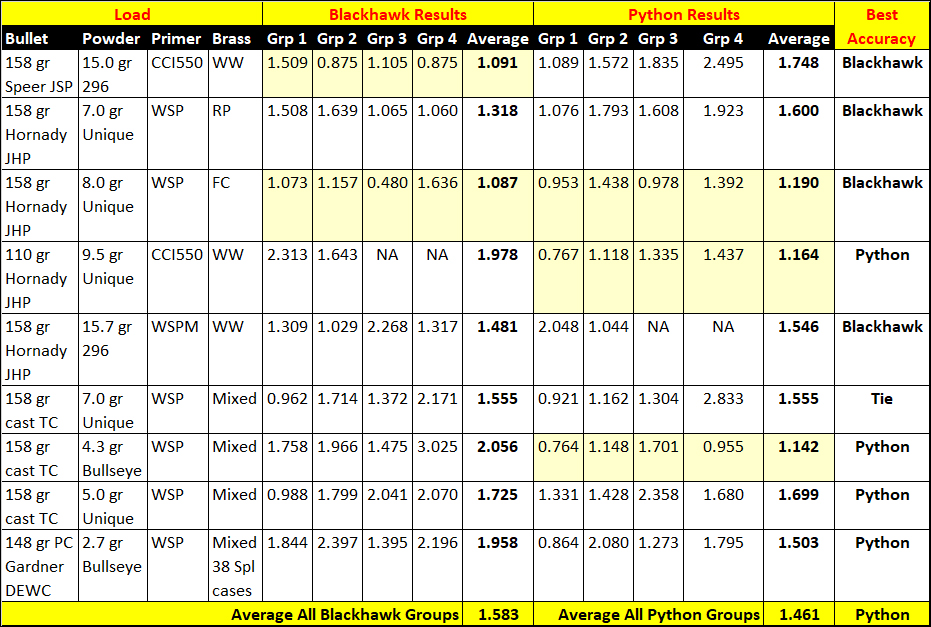

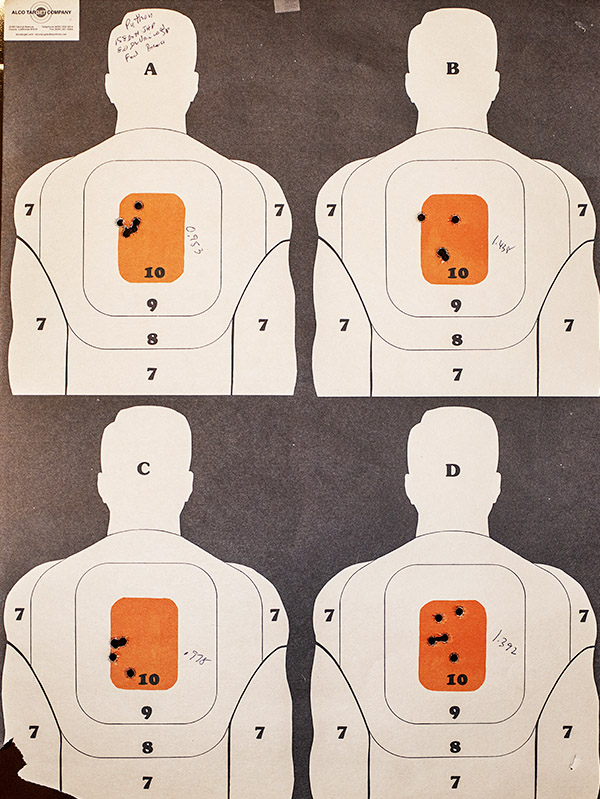

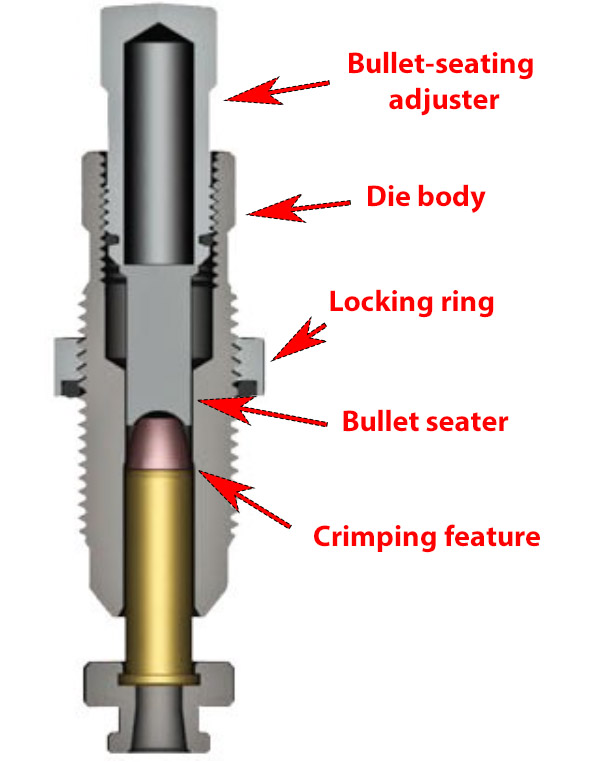

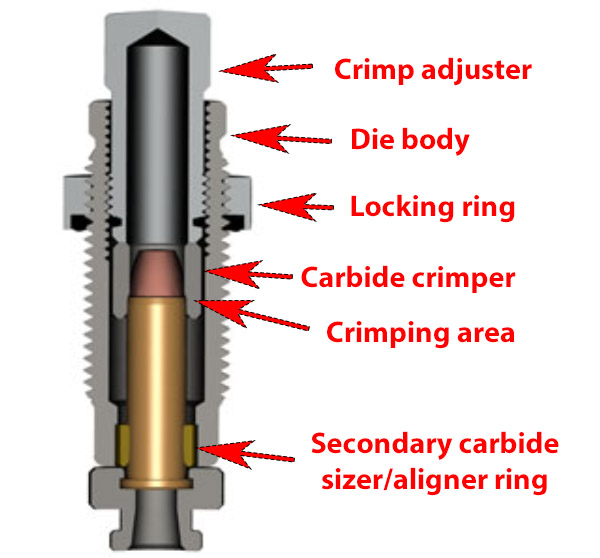

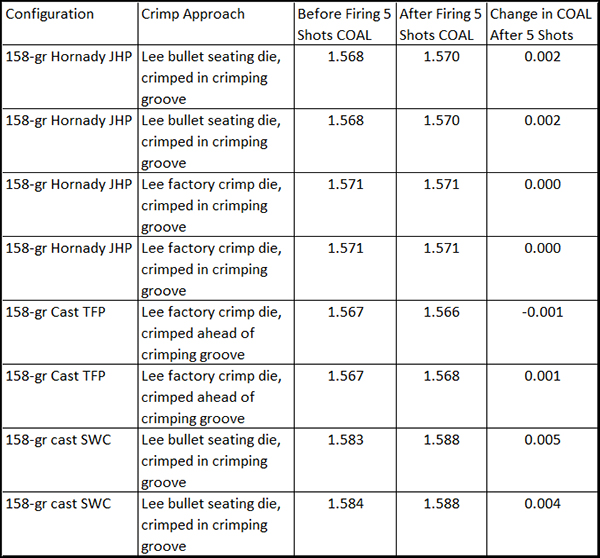

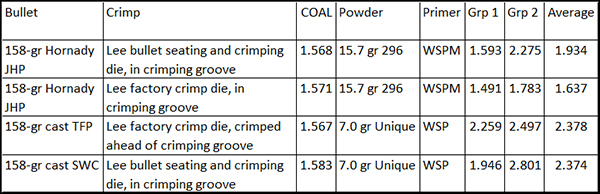

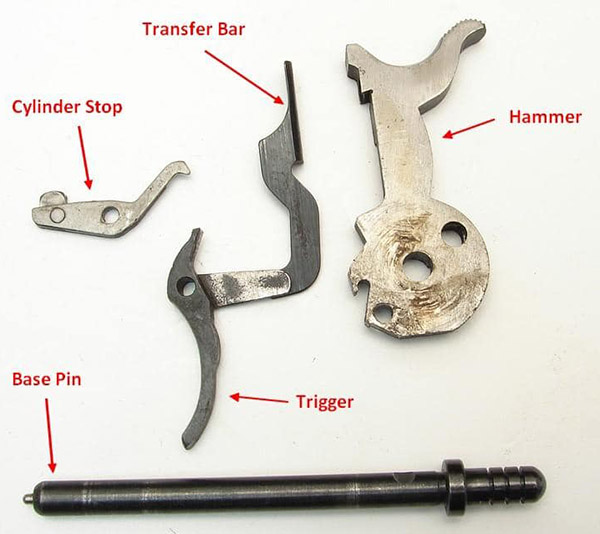

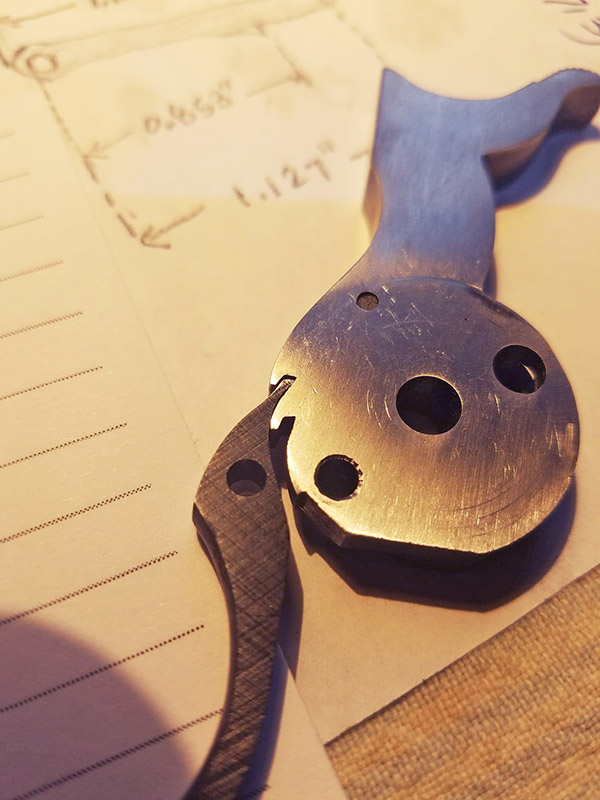

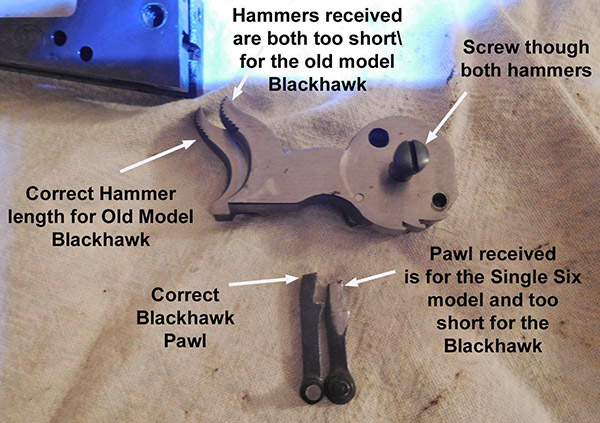

Finding the original parts for an Old Model Ruger is very difficult. Each part had to be purchased separately. It took several months to find all the parts and there were some hiccups along the way. Upon receiving some parts advertised as original Blackhawk parts, such as the hammer, I found that they were original parts for a Single Six model and were not compatible with the Blackhawk. Eventually all the original parts were acquired. The parts included a new hammer, trigger, base pin, cylinder stop, spring, screw, and pawl. The photos and captions tell the story about what it takes to restore converted guns and illustrates the differences between the original and retrofit parts.

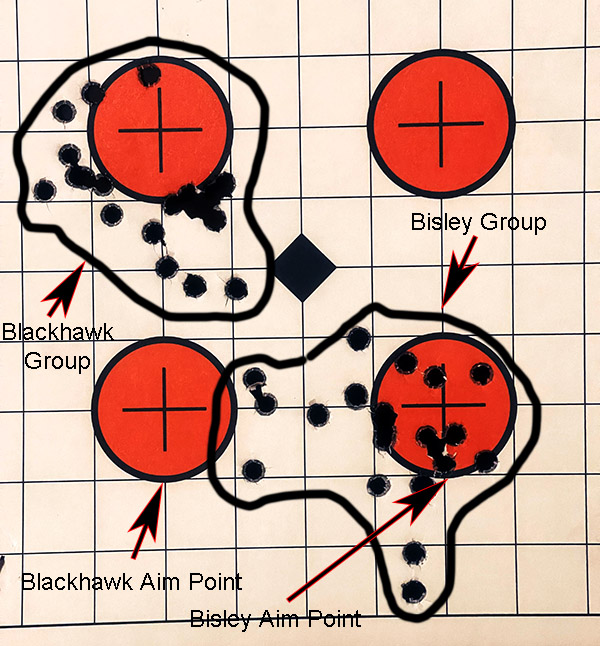

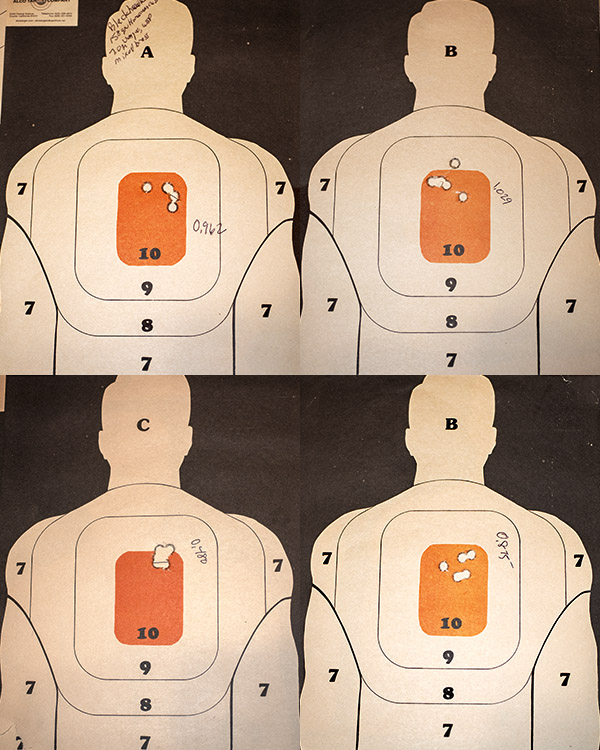

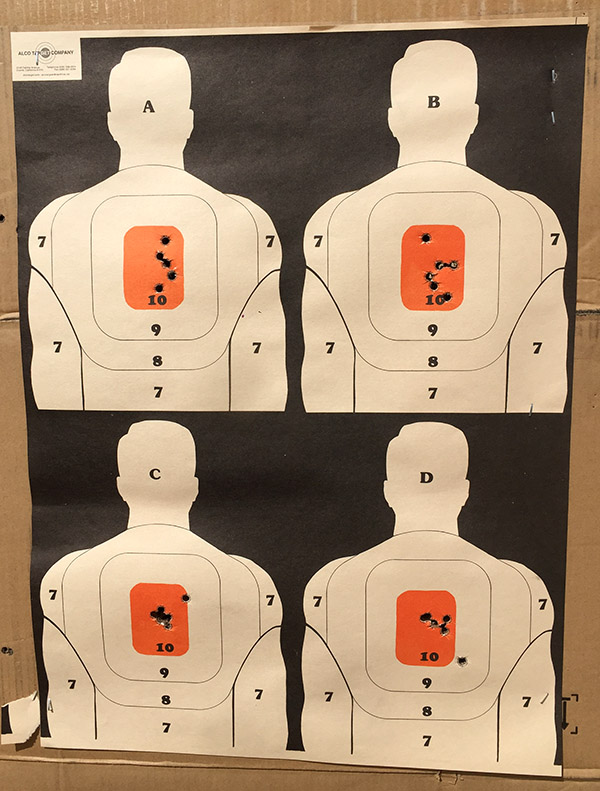

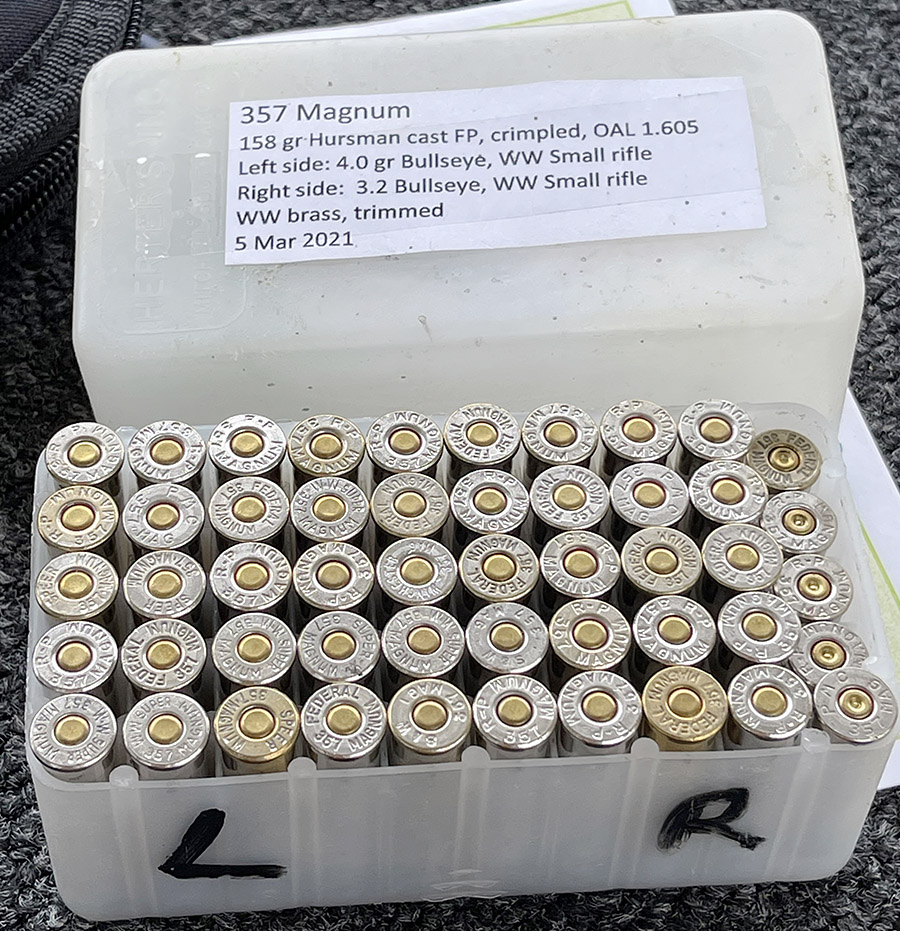

To make a long story short, all the original parts cost more than what I paid for the gun. But it was worth it. This is the smoothest Blackhawk trigger ever, and the accuracy is awesome. Only hand loaded, home cast Elmer Keith style bullets have been fired through it since acquired by me.

This Old Model Ruger has become one of my favorite .357 Magnum sixguns and I think that Skeeter would have approved of how this “parts gun” was salvaged.

Never miss an ExNotes blog: