The town of Weed is our last chance for gas or groceries. It’s a small place, population 20, and every Weed-ian citizen is packing heat. The chick working at the only store in town sports some kind of .45 auto that wobbles a crazy figure 8 on her hip as she totes pallets of soda pop from the storage shed into the store. The tall cowboy who delivers propane has a revolver on his hip also but that gun is not nearly as active.

Look there: a soccer mom wearing a white cowboy hat, plaid shirt, jeans and a 9mm pistol goes into the store for a gallon of milk. Mid-sized dogs hop out of a Polaris side-by-side, both dogs strapped with camouflaged vests that sport bandoliers of ammunition and pup-optimized night-vision goggles. Tactical mutts, man. A small child, not more than 2 months old waves about a menacing AR-15 while his head lolls in an elliptical orbit. Each complete cycle baby’s hard eyes lock onto mine and dare me to steal his candy before rotating on.

Okay, okay, I’m joking. The baby wasn’t carrying an AR-15. Needless to say, the crime rate is low in Weed. Either that or the woods are full of spongy ground and failed attempts. Mike and I fill our gas tanks at Weed not so much because we need fuel but because it’s more an offering to the forest gods before we leave civilization. Cover me while I pump the 87 octane.

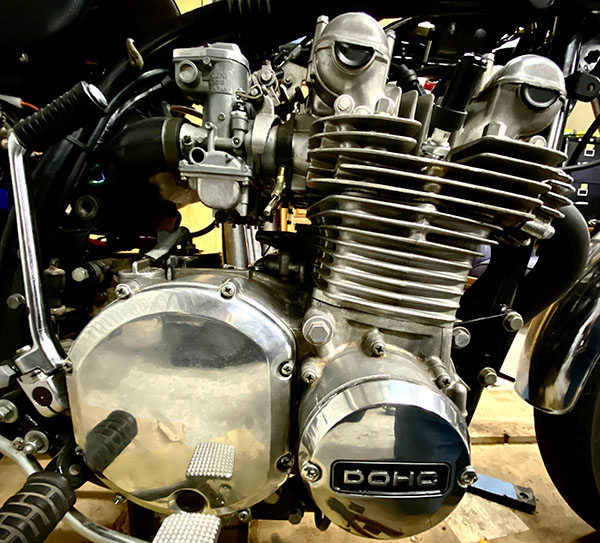

Mike has a BMW 650 and I’m on my Husqvarna 510. We leave Weed heading west and after the even smaller town of Sacramento, Aqua Chiquita Road rises into a dark green forest of pines and aspens. This is the Lincoln National Forest. National and state parks may be closed due to Covid but here in New Mexico rough camping in the forests is still allowed.

We originally planned on camping further west, on Thousand Mile Trail, but an interesting unmarked side road caught our attention so we wandered off to see where it went. You can do stuff like that when you have no destination.

The side road was bumpy and almost all rock. Not loose rock, but solid rock. We bounced along for a mile and the road dipped into a sandy mud hole. Off to the right was a wide, shallow valley covered in lush green grass and dotted with grazing cows. “What do you think?” asked Mike. “Lets go check it out.”

The valley was much smoother than the road. There were tangles of old barbed wire sprinkled among the cow patties. Each time we would stop at the perfect camping place another perfect camping place was just a little further ahead. We kept following the Valley Of Perfect Campsites until it split off into two directions. We made camp at the junction of the two valleys on a slight rise that gave a commanding view of the pastoral scene.

I mean camping doesn’t get any better than this: no people, no RV’s, the camp even had a pre-constructed fire-ring and enough firewood for a month. Setting up my new tent was easy. I’ve used pup-style tents for years and they are all the same simple sleeve with two poles. One modification I’ve learned over the years is to use bungee cords for tying off the end poles. In a hard wind the bungees stretch but don’t yank the tent pegs out of the ground.

The pup tent was easy enough to rig but my new air mattress made up for it. I bought a Soble brand mattress with a built-in pump. The deal is, you remove the cap and then the plug on the square pump area. Next you push down on the square pump to fill the mattress. And you pump. And you pump. I started grumbling, “This damn mattress pump isn’t doing anything!”

I pumped and pumped. Sweat started trickling down my sides and still I pumped. Then I tried inflating it by blowing into the fill hole. After 20 minutes of struggling I was light headed, feeling sick and getting nowhere. I gave up and tossed the completely flat mattress into the tent and my sleeping bag over that. At least we had soft grass under the tents.

We were drinking smoky coffee and cooking hot dogs on a stick over our roaring fire. It really was the perfect camp site. Mike asked me, “Tell me how your air mattress works.” I explained the cap and the plug and the little square built-in pump to him. Mike thought about it for a few minutes then asked me, “How do you deflate the mattress?” I was stunned. What a dumb-ass question: deflating the mattress was the last thing I wanted to do! Then Mike said, “There must be a way to let the air out.”

My world shattered. Dark, stumbling stupidity was illuminated by the light of one thousand suns. Of course! There had to be a second plug! I ran to the tent, all doubt erased. There, underneath the pillow on the opposite side from the pump was a 1-inch deflation valve and it was wide open. For 20 minutes I had been pushing air from the foot of the mattress out the valve on the other end. With the deflation valve plugged the Soble mattress took about 2 minutes to inflate into a firm, comfortable sleeping pad.

After the air mattress debacle I realized I should have brought some gin along. I’ll put that on my list of equipment along with more water. Making coffee, cleaning up and drinking used up most of our water supply. Mike had an emergency drinking straw, the king you put into any old water and it filters the muck. A stream runs alongside Aqua Chiquita road a few miles away so we weren’t going to die. Other things we brought but didn’t use were aerosol cans of bear spray and bear bells. The bells were CT’s idea. If a bear can’t hear me snoring then he’s a pretty old bear.

Speaking of snoring, I’ll need a new sleeping bag as the tiny mummy bag would not allow much movement. I finally un-zipped the thing so I could turn and parts of me fell out into the 50-degree night air. I woke up sore. But then I always wake up sore. That night air also soaked all our gear. The bikes were wet, our folding stools were wet, the inside of my tent was dripping with condensation and that’s with both sides open. Mike’s tent didn’t have a rain fly, the top is mesh and was still wet inside. I don’t know if this was just a function of the dew point or the tent material not breathing.

Hot coffee in the morning will pave over a lot of rough patches and by 11 a.m. we felt alert enough to head back down the mountain. We rode west on Aqua Chiquita until Scott Able Road and followed Scott Able back to the paved highway.

A brief discussion was held at the 1000 Mile Trail, our original destination but we were both kind of tired from our night on the hoof. Anyone who thinks homeless people are homeless by choice has never camped with me. I don’t like motorcycle camping and this trip has done nothing to alter my opinion. I guess it’s the new normal until things start re-opening and a treatment or vaccine for Covid 19 is created. I’m not going to complain too much. I’ve learned more on fine-tuning my camping gear, which was the goal on this ride. You know, waking up sore and damp beats not waking up at all.

. We’ve touched on it before with our book review on Revolver – Sam Colt and the Six Shooter that Changed America

. This is another book review, and a movie review, too, as Lonesome Dove

was also made into a four-part TV special

three decades ago.