The .357 Ruger Blackhawk

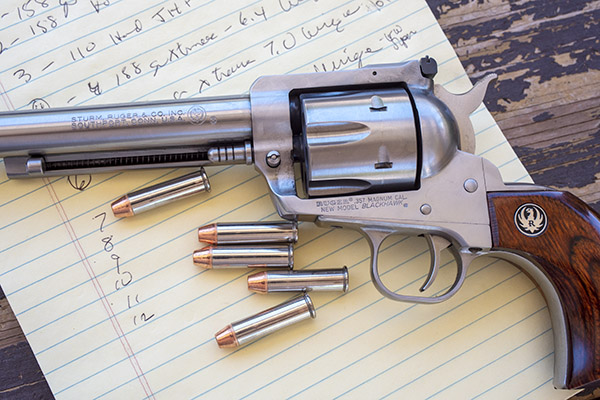

Ruger’s Blackhawk is an iconic firearm, one that’s been in production since the 1950s in one form or another. I bought my first one in a department store in Texas for under a hundred bucks back in the mid-1970s, and I’ve bought and sold several since. I wish I had not sold any of the Blackhawks.

I’ve owned a few .357 Magnums over the years…Rugers, a couple of Model 27 Smiths, a Model 28 Smith (remember that one?), a Model 19 Smith, and a Model 65 Smith. I’ve owned a couple of Colt Pythons, too. The Pythons were nice, but not nice enough to command the premium prices they pulled in the 1970s, and certainly not nice enough to pull the exorbitant amounts they sell for today. The Smiths were accurate, but they didn’t hold up under constant use with magnum loads. I had a new Model 27 that I wore out in a couple of seasons in the metallic silhouette game; it suffered from extreme gas cutting under the top strap and a cylinder that sashayed around like an exotic dancer in a room full of big tippers. The Ruger Blackhawks seem to last forever.

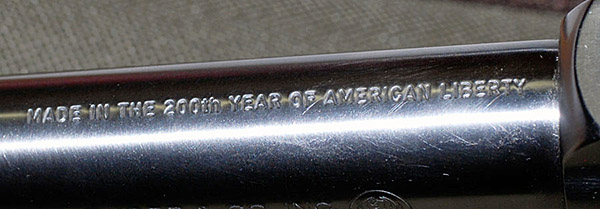

I’m down to one .357 Magnum now and it’s a 200th year stainless steel Blackhawk with a 6 1/2-inch barrel. It’s one of my favorite revolvers and it’s not for sale (it never will be; I learned my lesson about letting good guns get away). I have a few favorite .357 Magnum loads I’ve used over the last 50 years. I thought it might be a good idea to document how they did in the Blackhawk, try a few more to see how they do, and share it all with you here on the ExNotes blog. I guess this is the appropriate place for the disclaimer: These are loads that work well in my Blackhawk. You should never just take these loads (or any others from the Internet) and simply run with them. Always consult a reputable reloading manual (I like the Hornady and Lyman manuals best). Always start with lower charges and work your way up, looking for any signs of excess pressure, and go no higher if you see signs of excess pressure. Okay, so that’s out of the way. Let’s get to the good stuff.

.357 Magnum Accuracy Loads

I’ve played with a lot of different .357 Magnum loads over the years. I have a few favorite .357 Mag loads that have been superbly accurate in any of the .357 sixguns I’ve owned. That’s a bit unusual because frequently a load that is accurate in one gun won’t be accurate in another, but that rule doesn’t seem to apply here. The loads I like have worked well for me in any .357 I’ve ever shot. I verified these loads in my Blackhawk with this latest round of testing, and like I said above, I explored a few more loads.

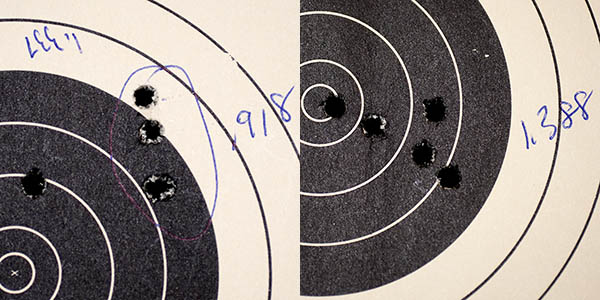

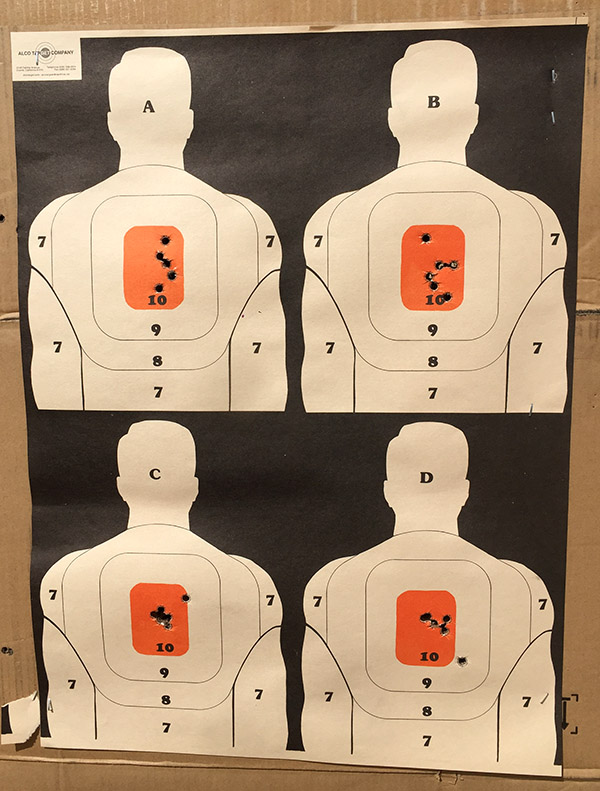

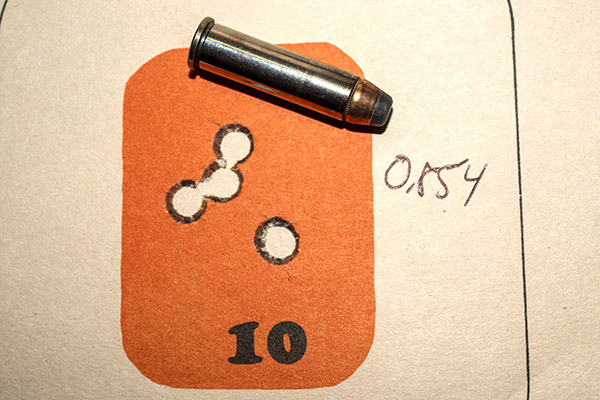

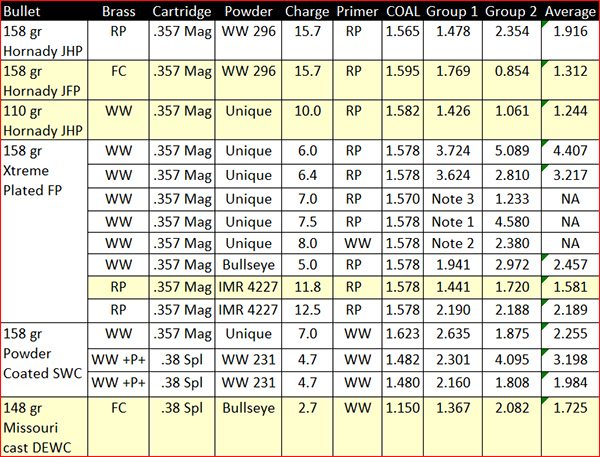

So, with the above as background info, let’s get into the loads. I’ll start with one of the standard “go to” .357 Magnum loads. That’s the 158-grain cast semi-wadcutter bullet (the Keith-style) over 7.0 grains of Unique. This is not the hottest .357 load (it’s a mild-recoiling .357 Magnum load), but it’s hot enough, it’s very accurate, and it’s relatively flat shooting. I have a guy who casts 158-grain flatpoint bullets for me and I like those with 7.0 grains of Unique even better than the semi-wadcutter bullets. The load is very consistent, and with the same zero and six o’clock hold I use at 50 feet (seen in the target below), I pretty much hit right on target at 25 yards, 50 yards, and yep, even at 100 yards. I was hitting a steel gonger last week at 100 yards consistently with this load. My shooting buddies were impressed, and after all, that’s what a lot of this is all about. This is a good load.

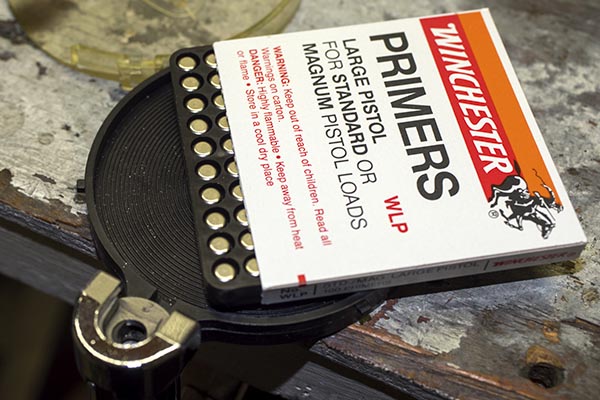

For hotter .357 Magnum loads, any of the Hornady 158-grain jacketed bullets (hollow points, flat points, and full metal jacket flat points) work superbly well with 15.7 grains of Winchester’s 296 propellant. These loads have a distinctive bark, high velocities, snappy recoil, and they are superbly accurate.

Another long time favorite load is a bit unusual but it’s accurate as hell. That’s the 110-grain Hornady jacketed hollow point and a max Unique load (10.0 grains of Unique, as listed in a Hornady reloading manual from the 1970s). I first tried this one 40 years ago when I had a Colt Python and I was impressed with its accuracy. I tried it again in this test series and the results were similarly impressive. It’s probably the fastest load I tested because of the max load and the light bullets. My old Hornady manual indicates the 110 grain Hornady bullet with 10.0 grains of Unique exits the muzzle at 1450 feet per second. That’s fast.

Plated Bullets: Are They Any Good?

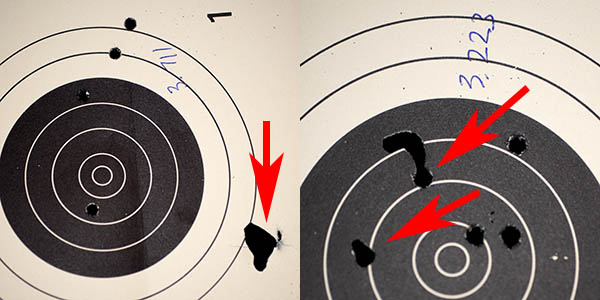

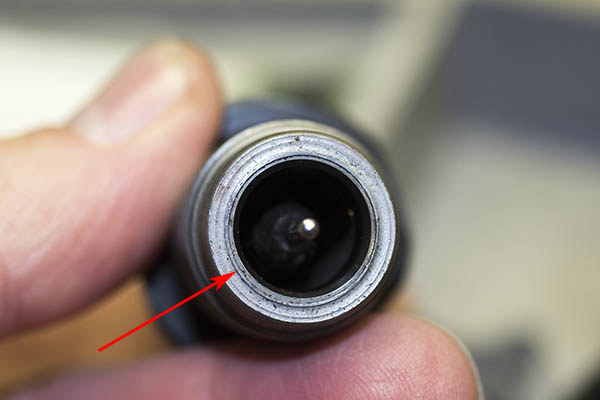

Surprisingly, the 158-grain plated flatpoint bullets I tested didn’t do well with any charge of Unique, and in the past, they have performed very poorly with 296 (the bullets frequently shed their plating in the bore). These plated bullets are offered by Berry and Xtreme. These are not jacketed bullets; the copper plating is chemically applied and the coating is very thin. I did get one decent showing with a lower-end charge of IMR 4227 propellant, but given the choice, I’d go for a plain cast bullet rather than plated bullets. You may feel differently. Please leave a comment here on the blog if your experience is different than mine.

Powder Coating and Paint Fumes

I tried powder-coated bullets last week, too, to see how they would perform. Powder coating is a concept that’s been around for a few years as an alternative to lubing cast bullets. I found that accuracy was more or less on par with lubed bullets, but not really any better. The powder-coated bullets look cool (the cartridges kind of look like lipstick). When I fired several powder-coated bullets fairly quickly, I could smell the paint. Some folks swear by these bullets and love them for IDPA and similar competitive pistol events. For me, performance was the same as conventional cast bullets. Your mileage may vary. Leave us a comment if you feel differently.

A Metallic Silhouette Load

When I shot metallic silhouette competition I used a 200-grain cast roundnose bullet in my .357 Magnum Model 27 Smith and Wesson. That bullet worked extremely well, and because of its heavy-for-caliber nature and high length/diameter ratio, it carried a lot of energy downrange. It was superbly accurate with 12.4 grains of 296. But finding those bullets is next-to-impossible today. It used to be a standard .38 Special bullet for police duty, but very few (if any) departments carry .38s today, and nobody seems to stock the 200-grain bullets. Maybe I need to get back into casting. I sure loved that 200-grain bullet in the .357 Magnum. They actually made the .357 Magnum work better on the 200-meter rams than a 240-grain .44 Magnum. The .44 Magnum wouldn’t consistently take down the rams; the 200-grain .357 Magnum did so every time.

.38 Special Loads

One of the great things about a .357 Magnum handgun is you can also shoot .38 Special loads in it. I guess that’s a good thing, as the .38 Special cartridges have lighter recoil. I tried three .38 Special loads with three different bullets. The accuracy load in .38 Special is a 148-grain wadcutter bullet seated flush with the cartridge mouth over 2.7 grains of Bullseye propellant. That load is super accurate in my Model 52 Smith and Wesson target pistol, and it did okay in the Ruger, too. I’ve always believed that a .38 Special cartridge would never be quite as accurate in a .357 Magnum handgun because the bullet has to make a longer jump to reach the rifling, and my testing last week did nothing to change my mind on that count. The .38 Special does okay in a .357 Magnum handgun, but I believe the best accuracy resides in a .357 case.

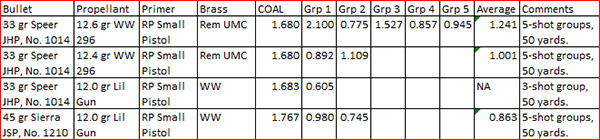

.357 and .38 Accuracy Testing Results

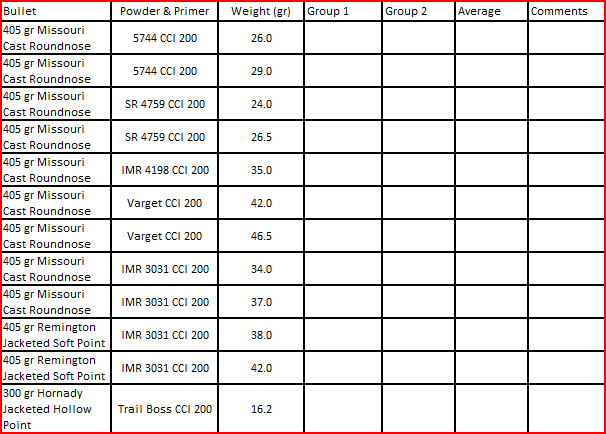

Here’s a chart summarizing my accuracy results:

There you have it. If you have a load that works well, please leave a comment. We’d love to hear from you.

Why you should click on those popup ads!

We have a bunch more good stuff on reloading, guns, and other shooting sports information. You can find it all on our Tales of the Gun pages.

Click on those popup ads!

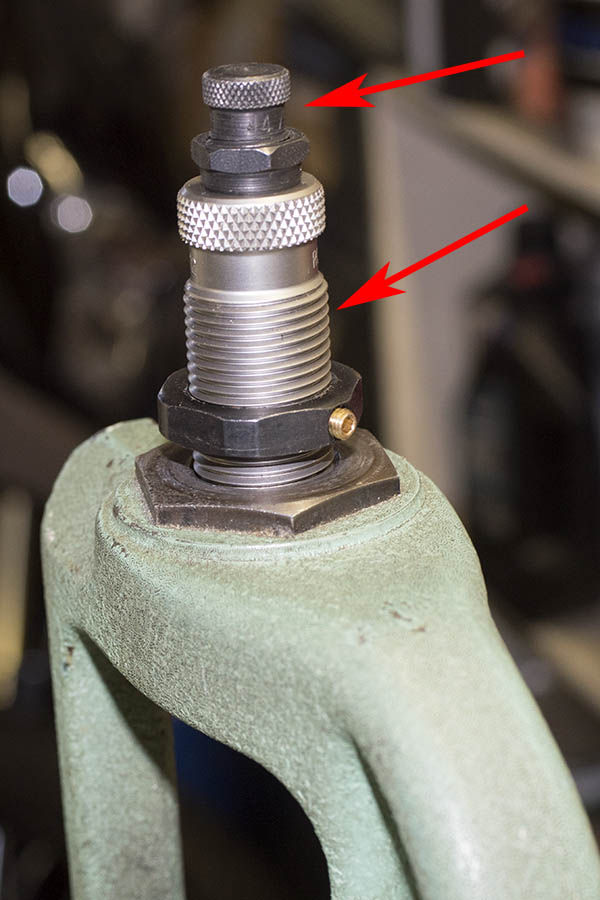

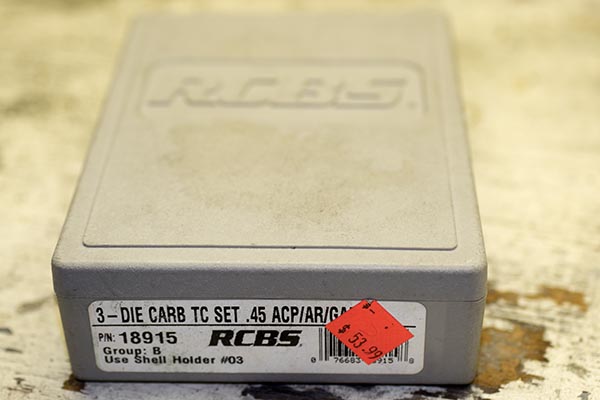

Buy RCBS reloading equipment here!

Never miss an ExNotes blog. Subscribe for free!