By Joe Berk

It had been way too long since I hunted pig, and that was a character flaw I aimed to correct. Baja John immediately said “Hell, yeah” when I asked if he wanted to join me on an Arizona pig hunt, and it was game on. I’ve known John for half my life, and that means I’ve known him for a long time. We’ve done a lot of trips through Mexico and elsewhere on our motorcycles. We know how to have fun.

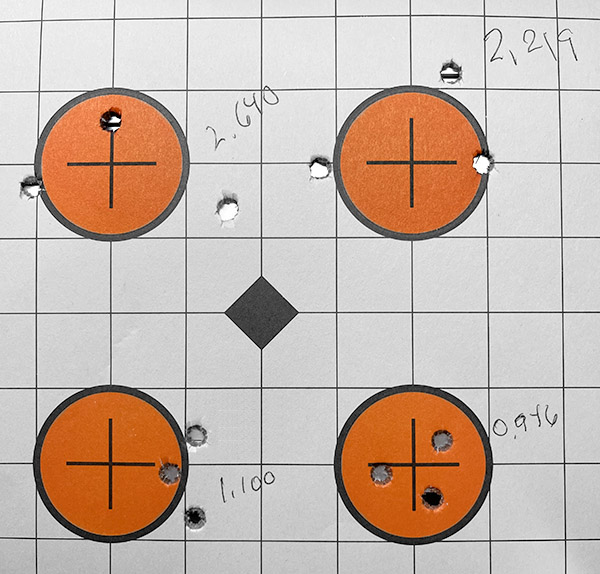

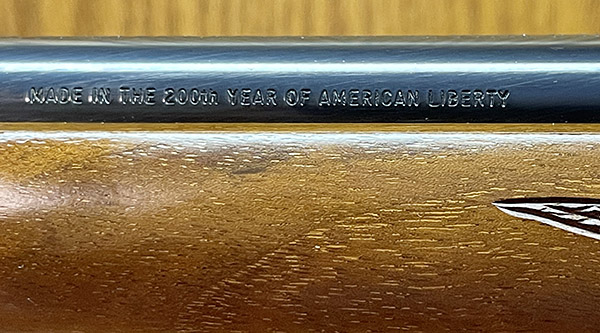

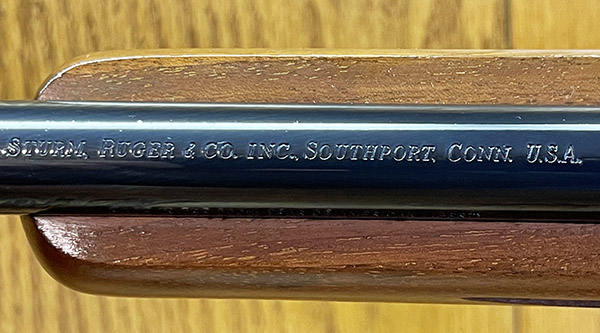

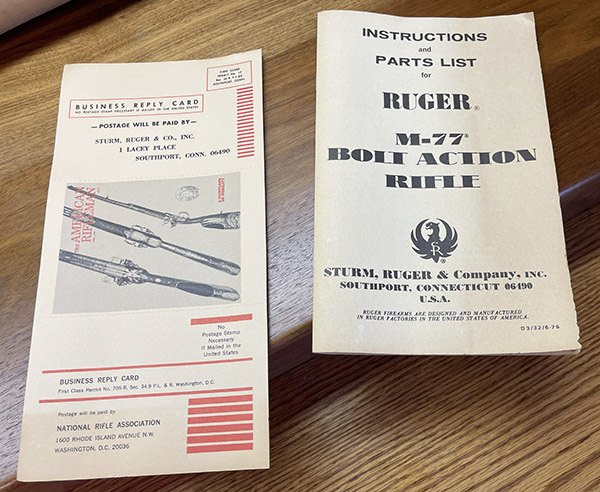

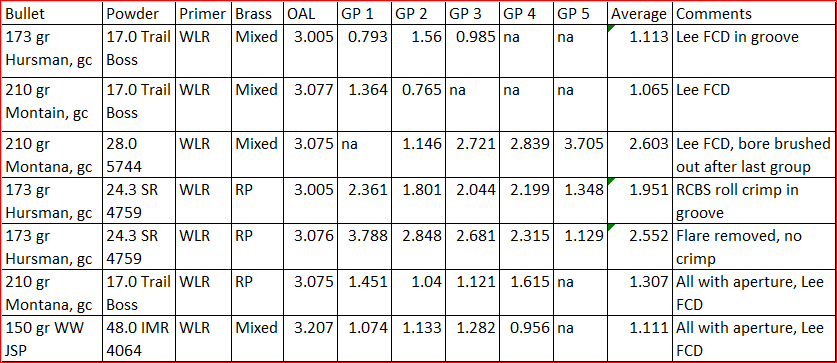

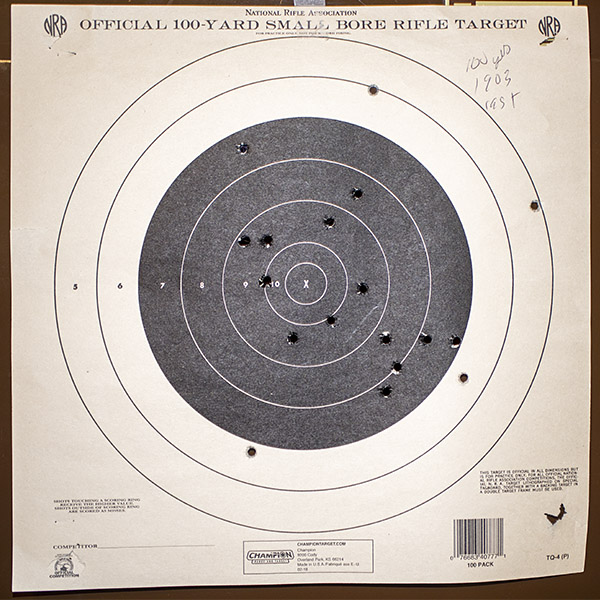

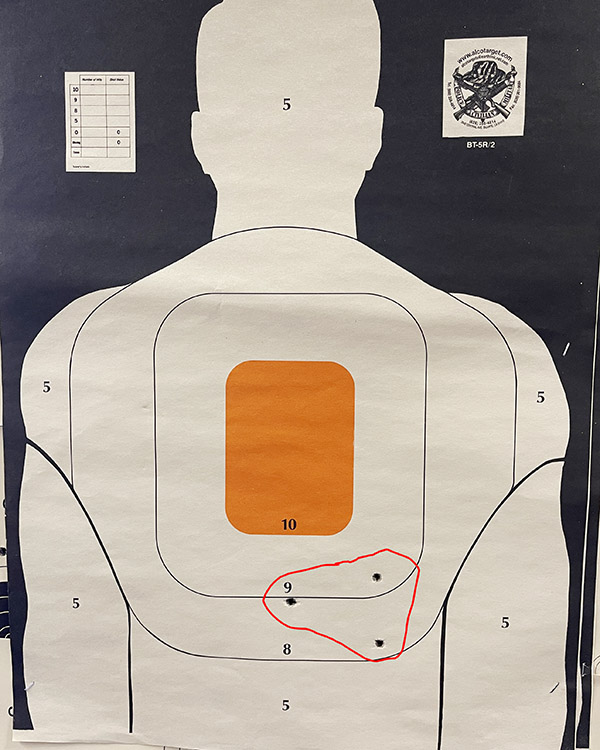

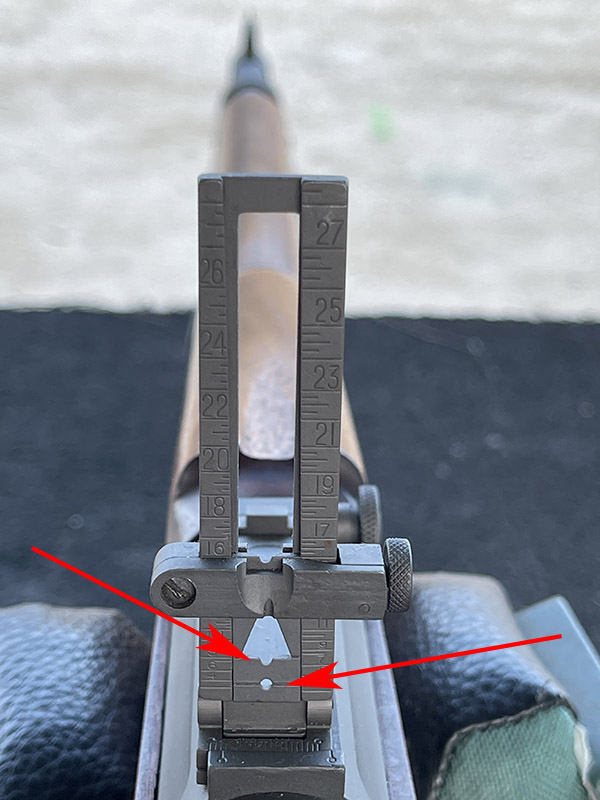

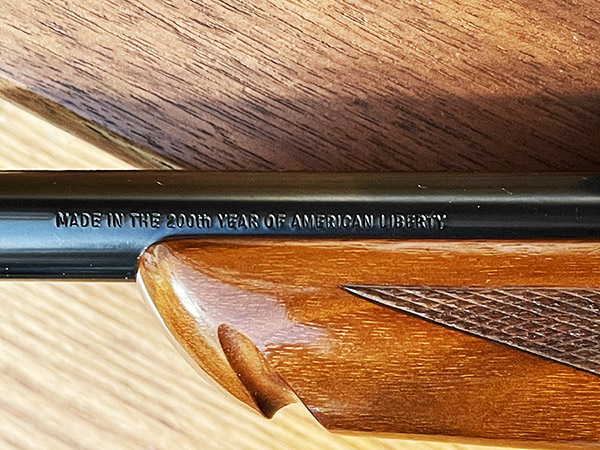

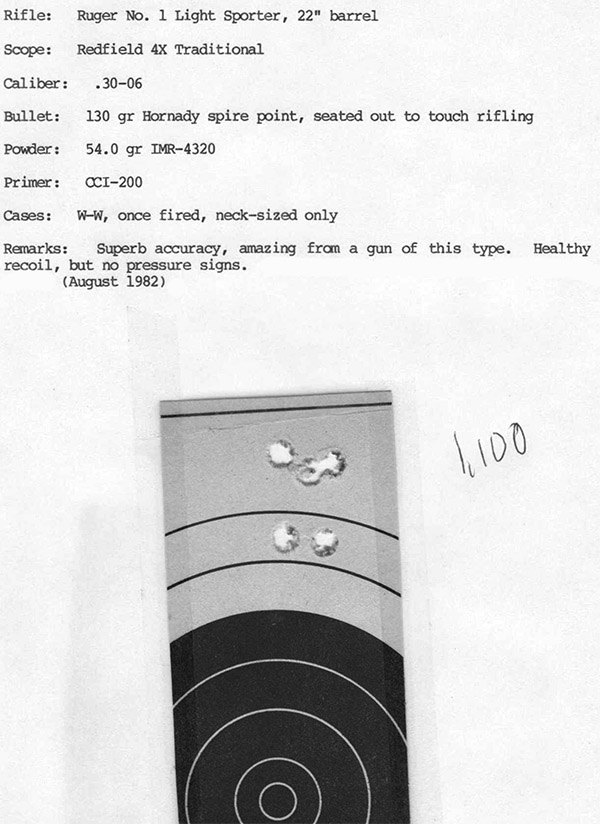

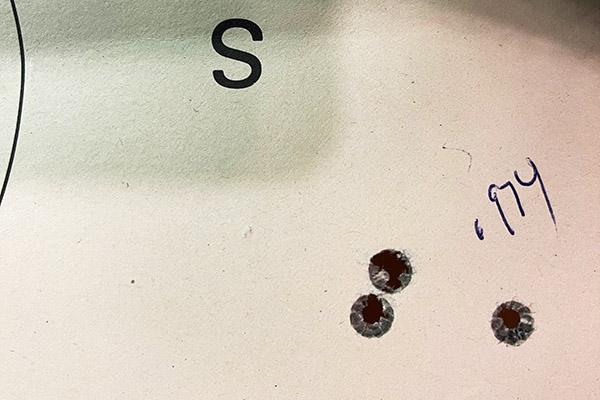

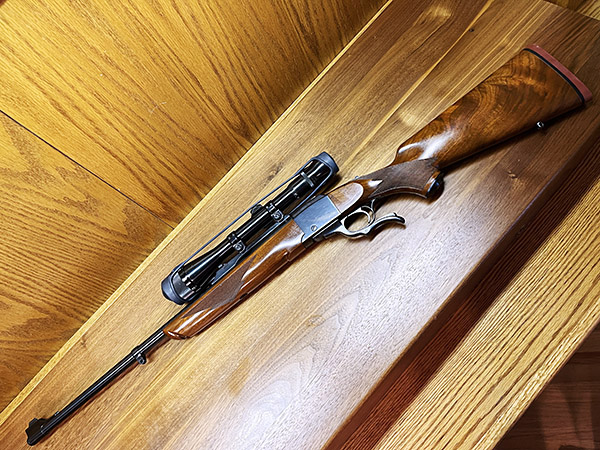

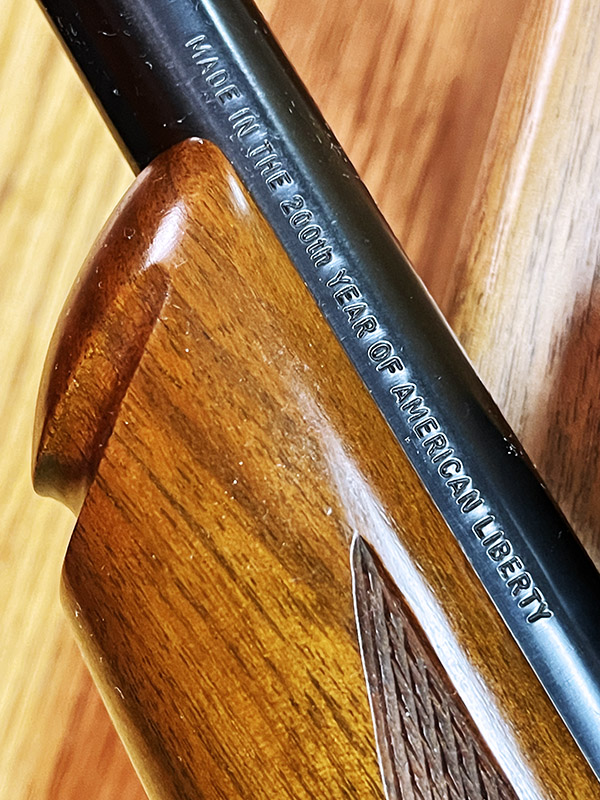

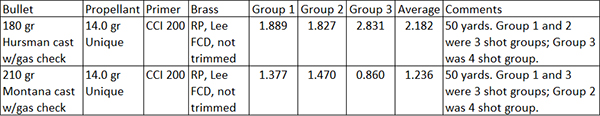

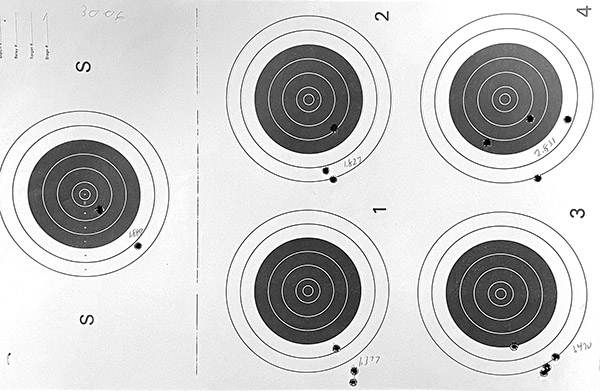

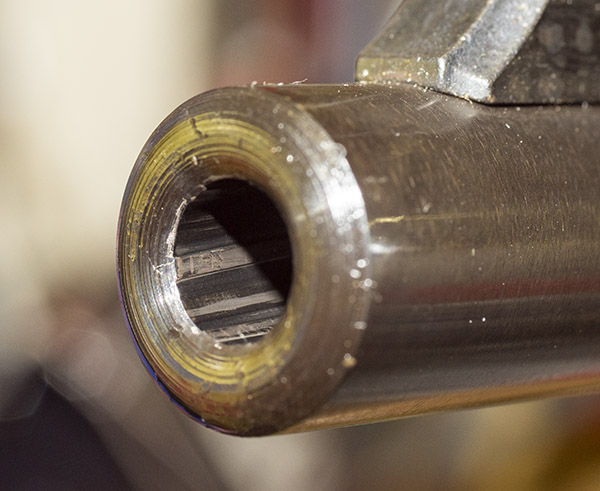

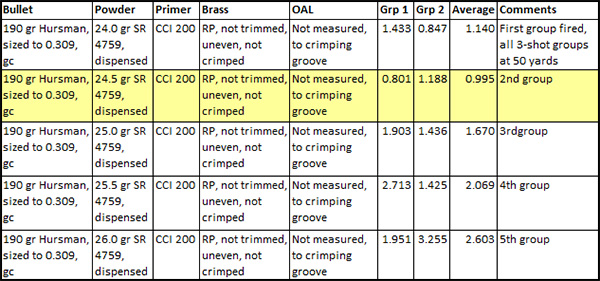

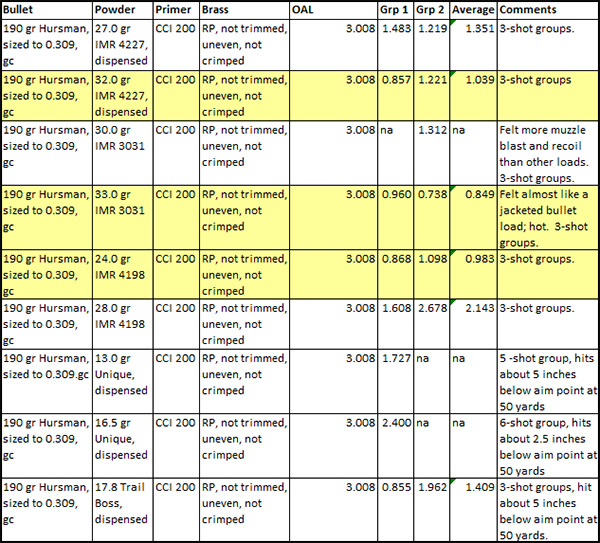

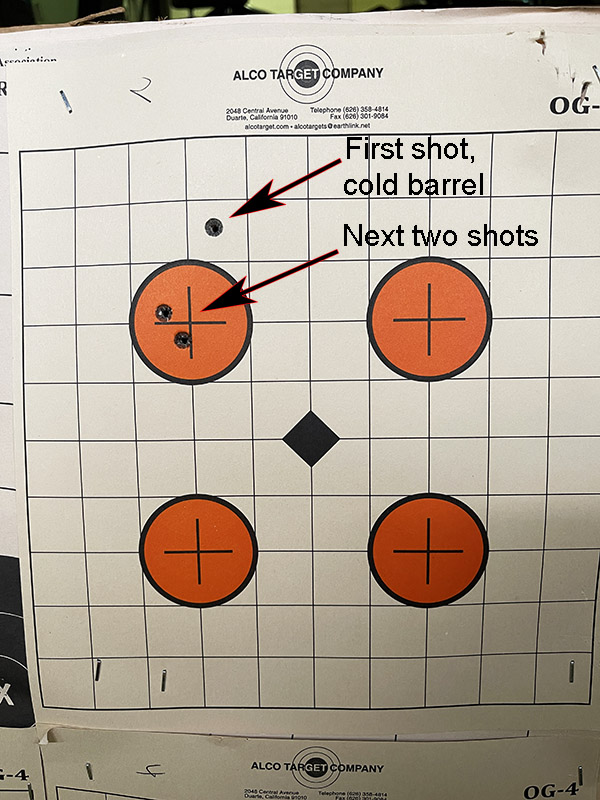

Getting ready for the hunt was nearly as much fun as the hunt itself. I knew I’d be bringing my 200th Year .30 06 Ruger No. 1A with me. It’s a rifle I’ve owned and hunted with for 50 years. You’ve read about it before here on the ExhaustNotes blog. On a previous hunt, I used Hornady’s 150 grain jacketed softpoint bullet in my Model 70 Winchester and it worked well. I had not developed a load with that bullet for the Ruger, though, so I set about doing that. The secret sauce was 51.0 grains of IMR 4064, which gave an average velocity of 2869.3 feet per second (with a tiny 14.1 feet per second standard deviation) and great accuracy. The load was surprisingly fast for the Ruger’s 22-inch barrel; the No. 1 shot this load at the same velocity as my Weatherby’s 26-inch barrel.

I knew I needed binoculars, which I already had, and a way to carry ammo (which I didn’t have). I found a cool belt-mounted ammo pouch on Amazon; the next day it was delivered to my home.

I had everything I needed; I loaded the Subie and pointed it east. We would hunt on the Dunton Ranch, about 325 miles away in Arizona. The weather was going to be a crapshoot. Everyone was predicting rain, and they were right. We would be lucky, though. It would be overcast and rain a lot, but not while we were in the field.

My six-hour ride under gray skies to Kingman was pleasant. It rained a bit, but it stopped just before I reached Kingman. Sirius XM blasted ’50s hits the entire way.

When I arrived at the Ranch, Tom (our guide) met me. John wouldn’t be getting in until later that evening. Tom asked if I wanted to hunt that afternoon, before Baja John arrived. You bet, I said, and we were off.

Scott Dunton keeps his ranch stocked with at least three flavors of hog, including Russians and Ossabaw pigs. I had not seen a Russian boar on my last hunt, and I would not see one on this hunt, but that’s okay. It’s good to set goals in life, and one of my goals is to someday get a Russian boar. It didn’t happen on my Dunton Ranch pig hunt a decade ago, and it wouldn’t happen on this trip, but we started seeing Ossabaws almost immediately. Wikipedia tells us that the Ossabaw pigs are descendants of feral hogs on Ossabaw Island, Georgia. The Ossabaws were originally released on that island by Spanish explorers in the 16th century. Imagine that.

Tom and I set out and like I said above, we saw Ossabaws fairly quickly. I told Tom that I really wanted to get a Russian. “They’re smaller, they’re harder to find, they’re nocturnal, and they’re mean,” Tom said. “Some boys out here last week got a nice one.” He told me he could set me up in a blind, but the odds of seeing a Russian were low.

A while later, we came upon a group of Ossabaws. Tom had a rangefinder and he scoped the distance at 117 yards. “What do you think?” he asked.

My mind was racing. I started thinking about Mike Wolfe on American Pickers. He often says the time to buy something is when you see it. You don’t know if you’ll ever see it again. I thought it would be cool to have John there when I shot a pig, but I didn’t know if we would see any later. I wanted a Russian; these were Ossabaws. But they were there. I could hear Mike Wolfe: The time to shoot a pig is when you see one. “Can I shoot one of these and then take a Russian if we see one later?” I asked.

“You can do whatever you want,” Tom said.

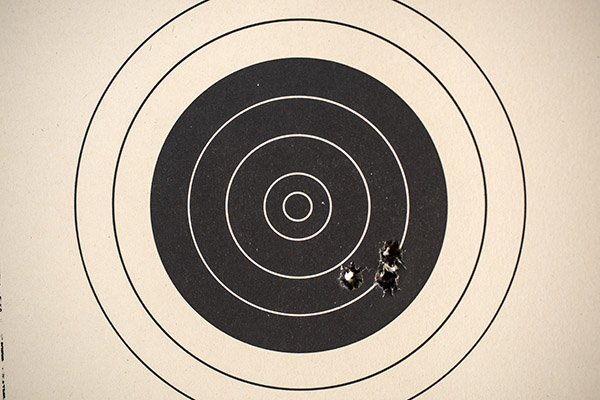

Tom set up his tripod, which is a cool field version of a rifle rest. I had never used one before (I’d never even seen one before). I looked at the Ossabaw 117 yards away through the 4-power Redfield. The hog was standing broadside to me. Fifty years ago, I used to shoot metallic silhouette pigs that were a third that size at three times the distance (385 meters, to be precise), with no rest, shooting offhand. But that was 50 years ago. My eyesight isn’t what it used to be, my ability to shoot a rifle offhand isn’t what it used to be, and hell, I’m not what I used to be.

It was time. I rested the Ruger in the tripod rest and held on the hog’s shoulder. I watched the reticle sashay around against the hog’s dark form and started applying pressure to the Ruger’s trigger. Things felt right. I was in the zone. I didn’t hear the shot, and I didn’t feel the recoil, as is always the case for me when hunting. The hog fell over, away from me, just as a metallic silhouette javelina would do.

“That was a nice shot,” Tom said. I don’t think he said it because I was the client. He probably sees a lot of misses out here from other clients. The hog’s rear legs twitched in the air.

“Should I put another round in him?” I asked Tom.

“No, he’s gone,” Tom answered. “It would just destroy more meat.” I looked again and the hog was still.

We walked up to the hog. I could see where the bullet entered (satisfyingly just about where I had aimed). I was surprised; I could not find an exit wound. When I .30 06’d a hog at the Dunton Ranch on my last visit, the bullet sailed right through. Not this time, though. More on that later.

I posed with my Ossabaw for the obligatory Bwana photo. Tom and I struggled to roll El Puerco over. We tried to lift it onto the back of the truck and could not. Tom told me he needed to get the trailer (which had a winch), and he told me he would drop me off at a blind. “You might see a Russian come by,” he said. That was enough for me. “I’ll come back out here later with John to pick you up.”

I got comfortable in the blind, which overlooked a watering hole about a hundred yards away. I scoped everything I could through my binoculars, imagining every rock and bush in my field of view might be a Russian. I felt like a Democrat looking for the imaginary Russians (I really wanted to see one, but they just weren’t there). A small group of Ossabaws showed up at the watering hole. I watched them through my binoculars. They did what pigs do, and then they started meandering around a bit. Towards me.

Golly, I thought. The Ossabaw hogs were getting close. Then, they literally walked right up to the blind. I could feel it rock around as the pigs rubbed up against the walls. They know, I thought. I had shot Porky (or maybe it was Petunia?) and it was payback time. They had come for me.

I could hear the pigs grunting just below the blind’s window. I remembered my iPhone. I took a picture, holding the phone just outside the window. I don’t mind sharing with you that I was more than a little bit afraid. My Smith and Wesson Shield and its nine rounds of hot 9mm ammo were back in the Subie. The sportsman-like snob appeal of hunting with a single-shot rifle suddenly didn’t seem like such a good idea. I had my one round I could put in the chamber, but I wouldn’t be able to reload quickly enough if the pigs wanted to exact their revenge on me. One shot. I was the Barney Fife of pig hunters.

Nah, I thought, these are just pigs being pigs. Or were they?

If you crank up your computer’s volume all the way up and listen, you can hear their grunts.

An hour or so later, Tom and Baja John were back in the truck. No Russians had wandered by. I was glad John had made it okay but I was disappointed I had seen no Russians. I imagined I knew what Adam Schiff must have felt like when Robert Mueller testified before Congress. Where the hell are these Russians?

Stay tuned: El Puerco Part 2 airs tomorrow!

Join our Facebook ExNotes page!

Never miss an ExNotes blog: